Words Posy Gentles Photographs Charles Williams, Lalo Borja, Christian Trippe

Couple in a Field, oil, Charles Williams

‘It’s horrible being an artist,’ sighs Charles Williams, the artist. ‘You get all excited and hope people will like it.’

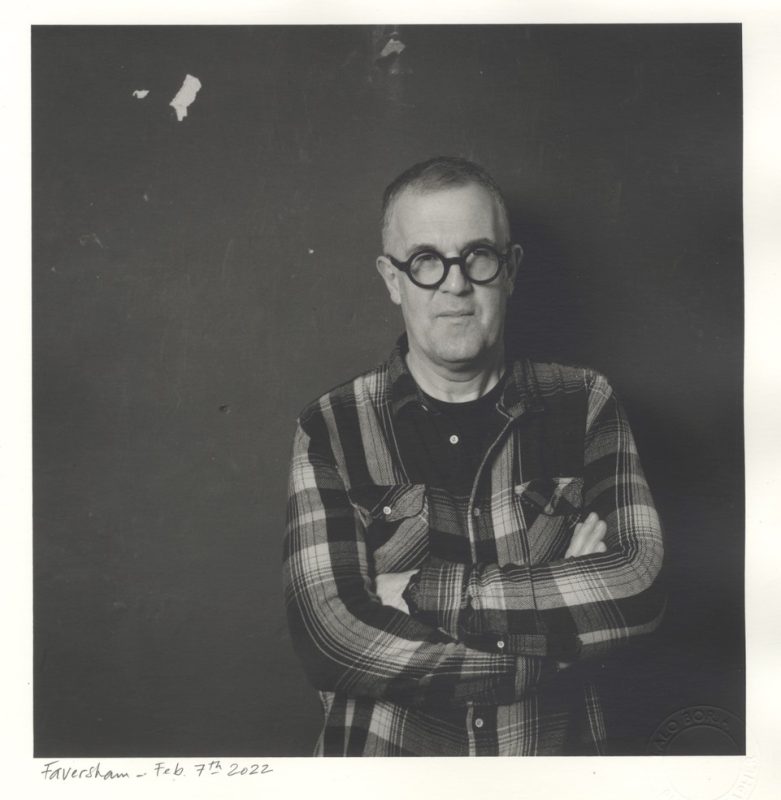

We stand in his Faversham studio on the third floor of his tall house, beadily eyed it seems, by pink and white bears, a sprauncy spotted horse and a couple of stoutish dogs, from their paintings on the walls, leaning against the books or on the table. Only the woman in the red dress too short to conceal her bony knees, arms held stiffly out to her sides, looks uninterested.

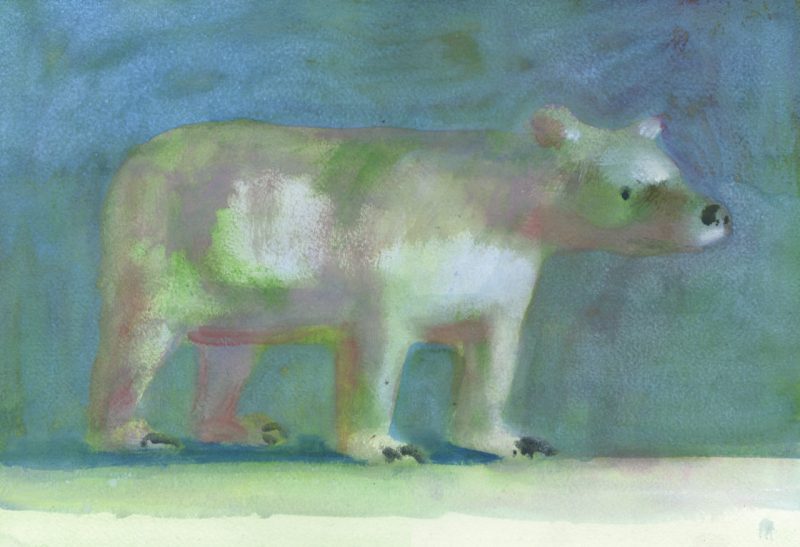

Charles suggests that while Francis Bacon’s paintings revealed the animal in the human, Charles’s find the human in the animal. Charles says of his animal paintings: ‘I aim for an almost humanness. I want them to be presences, looking back at you.’

Fat Pink Dog, Charles Williams

Big White Bear, watercolour, Charles Williams

His animals have expressions of intention and surmise, and look at the viewer in a way that the humans he paints do not. They can be funny, often disconcerting and disturbing, and uncute. Charles is a tease, sometimes seeming to suggest that there are people looking out of these animals – one painting of a bear is called ‘Bear Suit’.

Sometimes humans and animals inhabit the same painting and often it is the animal who has the upper hand. The sinister Alan, Gryff and John series (see below) show a flailing shirtless man being man/dog handled by a group of men and animals. The ‘Pantomime Horse’ figures have no costume but the front legs figure has a real horse’s head. He looks loftily just above our heads with his monocular eye, while the ungainly back legs figure in loose black pants grasps him anxiously and is uninterested in us. These hybrids have happened before. Scroll through Charles’s instagram (Charleswilliamsinsta) and find The Pink Boy Dog, Horse Boy and Drunken Dog Man. There are also transformations: Actaeon, a thin-limbed man with receding hair, stumbles as he glances anxiously at his sprouting tail.

Charles sometimes paints his animals with the colour called ‘Flesh Pink’ and a non word-mincing friend suggested they looked as though they had been flayed.

Alan, Gryff and John, Charles Williams

White Dog, Charles Williams

The people Charles is painting often seem unaware of the viewer. Charles shows me the model for the bony-kneed woman in the red dress, taking a tiny Preiser model railway figure from among others on the shelf. It is so small that I have to put on my glasses to see it in any detail. He shows me others: two figures in a hostage situation, a man holding a woman in a yellow dress and pointing a gun at her head; a woman sitting with her legs apart, blowing a huge bubble. Charles has painted her too. The tiny figures (all Caucasian as Charles point out) are painted in Madagascar. The human in these figures was lost far back down the line. ‘I draw them,’ he says, ‘then paint them as though they are real people.’

Parrhasios On The Beach, oil, Charles Williams

The writer Will Self is fascinated with Charles’s art and has written an essay about it which can be found in the publication, Charles Williams. Charles says that Will Self found his figures boneless; as though if you sliced them, they would be the same texture all the way through. ‘Together we came to the idea of “rubberiness”.’

Charles could draw and paint flesh, blood and bones if he wanted to, but he doesn’t really see any point these days: ‘I spent a long time learning how to draw. I went to the Royal Academy. I have written books on how to draw and taught people how to draw. But nobody needs it now. The rendering of form is a redundant skill.

‘But I still have this skill, so the question is what to do with it. Why am I compelled to do it? – that’s why I paint. The whole of painting for me is to do with self-doubt and self-questioning.’

Long brown dog, Charles Williams

He says he struggles to maintain his interest in his work, cursing and swearing when he realises the same thing is happening. For a while he tried to paint still lives. ‘I wanted to stop telling stories about animals and people, so I could just paint.’ Then Charles started to realise why the French call still life nature morte and that his paintings were all about death. Skulls rolled around in the fruit, and guttering candles and broken glasses took on a morbid aspect. ‘It gave me the heebie jeebies,’ says Charles. So monkeys started creeping into the paintings, among the bottles, glasses and candles.

Portrait of Charles Williams by Lalo Borja

Charles, a founder member of the Stuckist art movement, says: ‘Painting is all you need. It has all the things you ever need to happen in it.’ Other biographical facts, details of future shows and buying Charles’s work can be found on the website of his gallery, New Art Projects in London. Charles will also be selling monoprints of his work for the Art Car Boot Fair which is happening on May 14-17 and his painting is on the Royal Academy Summer Show shortlist as we write.

New Art Projects exhibition. Photo: Christian Trippe

Text: Posy Gentles; Photographs: Charles Williams, Lalo Borja, Christian Trippe