Words Richard Oldfield Photographs Matthew Hollow

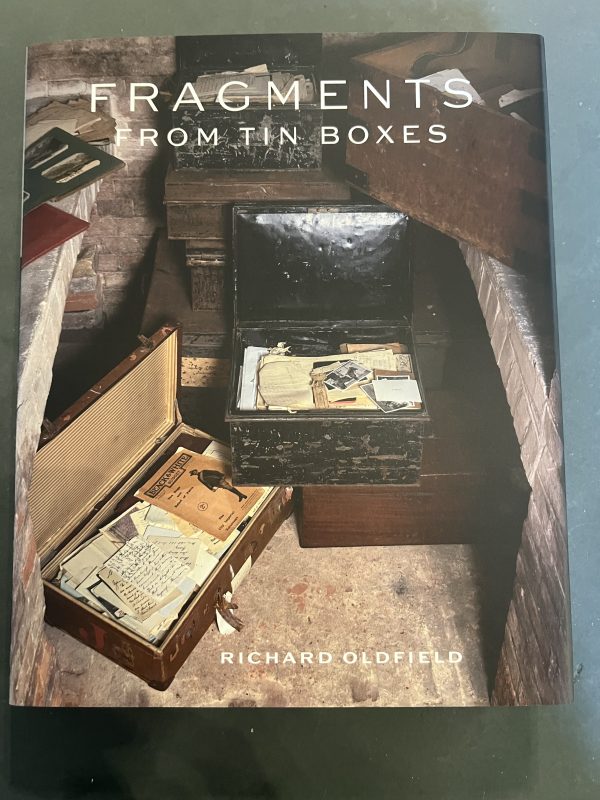

The story of a house is the story of those who have lived there. Fragments from Tin Boxes is the story of Doddington Place, a few miles from Faversham, based on the dozens of papers and letters retrieved during lockdown from tin and wooden boxes in the house. Many of the letters were in bundles of dozens, even hundreds, of exchanges between people separated by circumstance, usually war. These bundles, done up with string or pink ribbon, had never been looked at since first the string or ribbon was tied by the surviving correspondent. There were bundles from the 1830s, 1850s and 1890s of letters between men serving in India in the army, civil service or judiciary and their wives, safe in Simla or back in England.

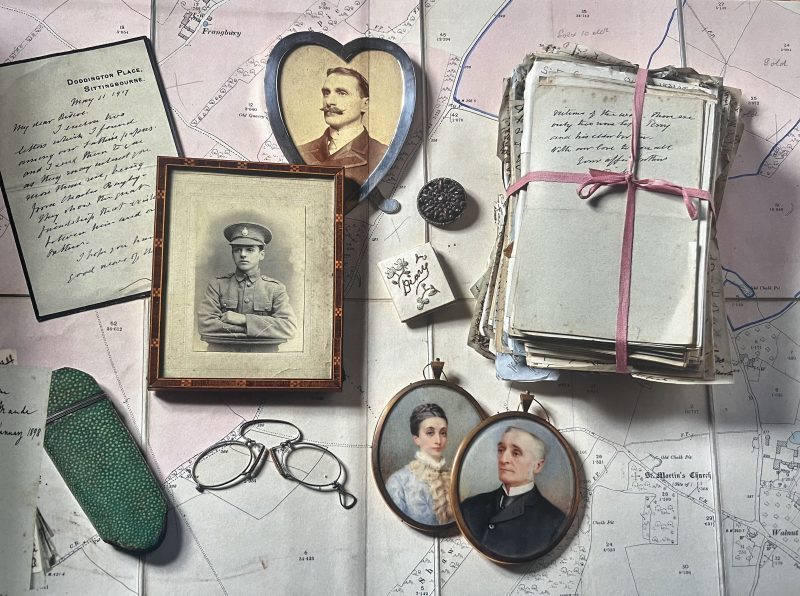

Some of the fragments from tin boxes

All these preceded the Oldfield family coming to live at Doddington Place, near Faversham. Maude Oldfield met her husband Douglas, who became General Jeffreys (referred to by Winston Churchill, a war correspondent with the Malakand Field Force, as ‘a nice man but a bad general’), when she was living with her widowed father, Sir Richard Oldfield, in Allahabad in the 1880s.

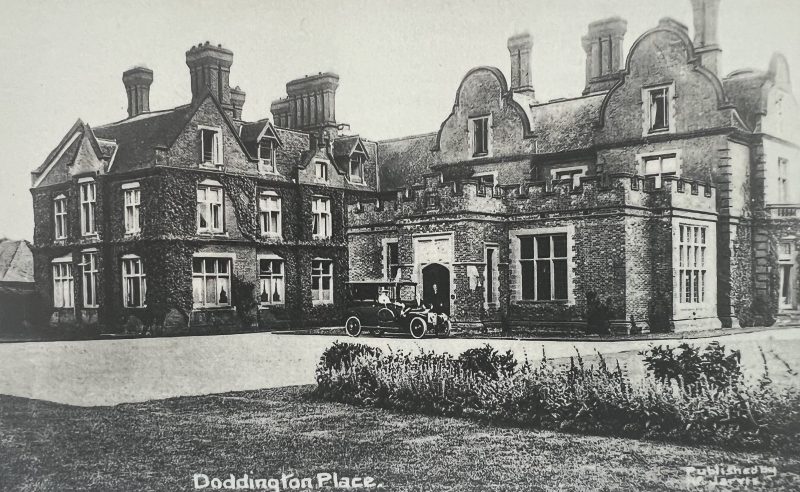

They married in 1897 and returned to England in 1899. In 1906 they bought Doddington Place and its estate from the Croft family who had had it built in 1860.

Doddington Place after the addition, in 1910, of the crenellated hall

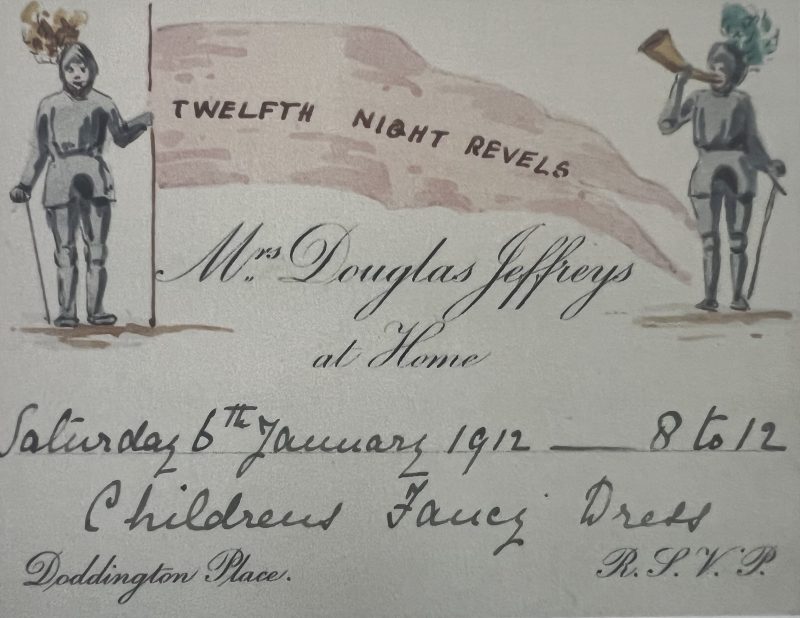

In the next eight years Doddington Place flourished. In a last splurge of Edwardian extravagance the Jeffreys added a large panelled hall, with crenellations – they referred to it grandly as the Great Hall – to the front of the house to allow them to put on big parties. Maude, formidable and commanding, was the expansionist party-giver; Douglas, considerably older, benign and cautious, trotted along complaisantly with her ideas. There were dinners and dances, tea parties for local children, shooting weekends.

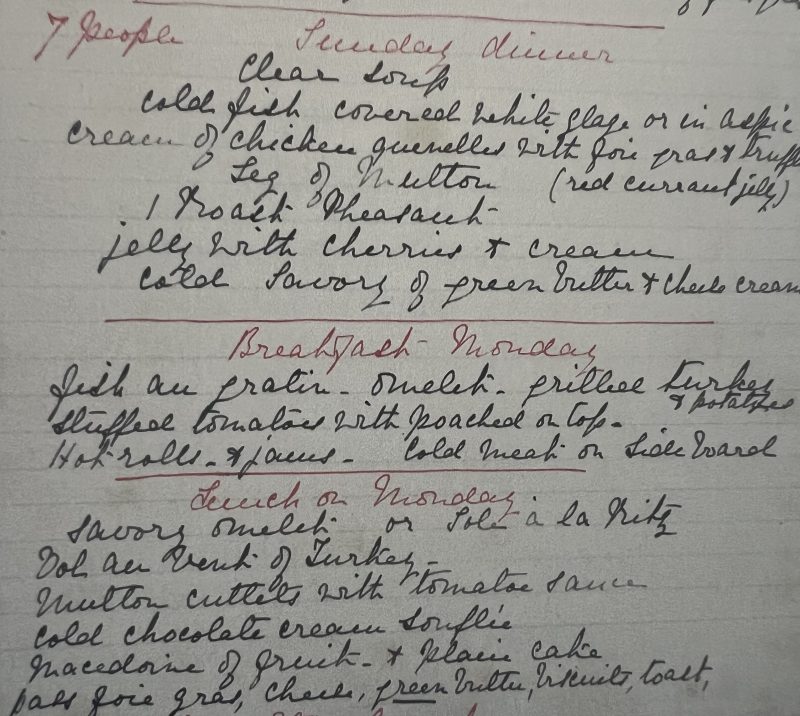

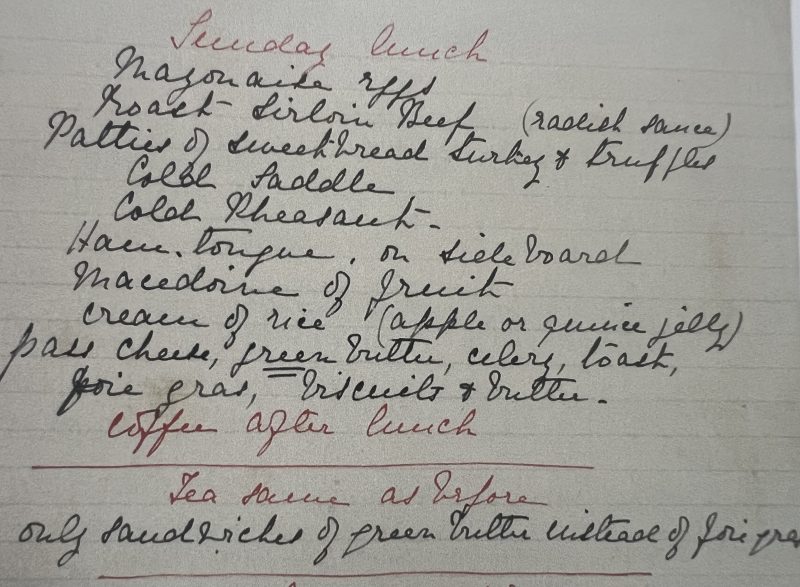

Maude Jeffreys in front of the newly planted formal sunk garden

The menus for all of these, preserved in the tin boxes, were astonishing. Before staggering out to go shooting, for instance, the guests had a breakfast of sole, pheasants and potatoes, ham, tongue, rolls and quince jelly or honey – to replenish them after their dinner the night before of soup, turbot, mutton cutlets farced with foie gras, roast turkey stuffed with truffles, partridges, raspberry cream, and an anchovy savoury. After a morning shooting more pheasants they were revived by a lunch of jugged hare, chicken and ham pie, plum pudding with brandy butter, and Stilton cheese, and there was shooting again in the afternoon. Then it was time for tea: chocolate, Madeira and Queen cakes, shortbread, and foie gras sandwiches and bread and butter and strawberry jam. Dinner was spinach soup, fish, sweetbreads, mutton, pheasants, Princess pudding, anchovy and cheese savoury. And so on.

A daunting gastronomic extravaganza

In the midst of the partying was Guy Oldfield, Maude’s nephew. In the army from 1908 and often away from England, he was nonetheless much the most frequent visitor. Maude, who did not have children herself, adored him. Only someone in very special favour as he was would have dared to disfigure the Visitors Book with jokey drawings of rabbits. His letters to Maude were long, chatty, relaxed, conversational, not at all literary. He was always cheerful, and made friends easily.

Each invitation was hand-painted

In December 1913 he stayed at Doddington before leaving to join his regiment in British East Africa. Several times on board ship on his journey through the Suez canal to Mombasa he wrote to Maude, and also, concentrating on the exploits of his much-travelled spaniel Gib, to his grandfather Sir Richard . When war broke out in August 1914, Sir Richard was relieved that Guy seemed out of the way of it. But in early September 1914 the butler entered the drawing room where the family were gathered and announced that there was terrible news from Africa: Mr Guy had been killed. Sir Richard fainted and nearly died. Maude was distraught. Guy had been killed by German soldiers in a skirmish near the River Tsavo which was the boundary between British and German East Africa – now Kenya and Tanzania.

Together the outbreak of war and the death of Guy brought to an end the halcyon days of Doddington Place under the Jeffreys. Guy, though non-resident, had been the central figure, the star around whom all the entertaining and all Maude’s hopes revolved. There were no more dances. Douglas died in 1922 and Maude remained in the house, almost reclusively, until her death in 1954.

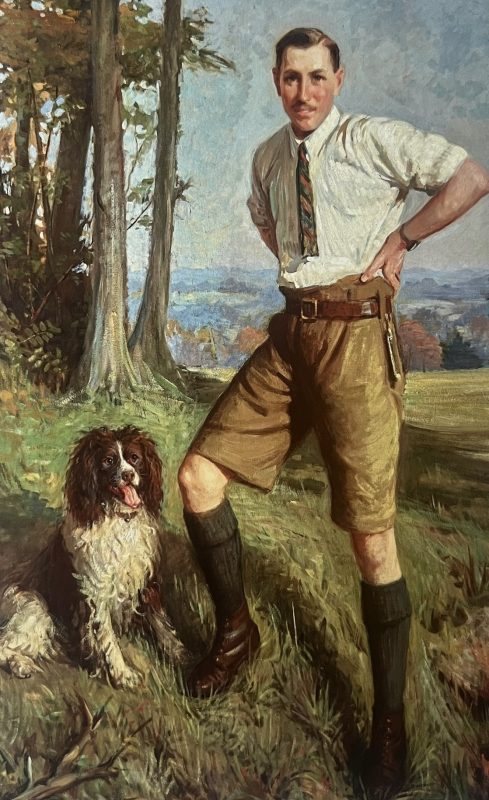

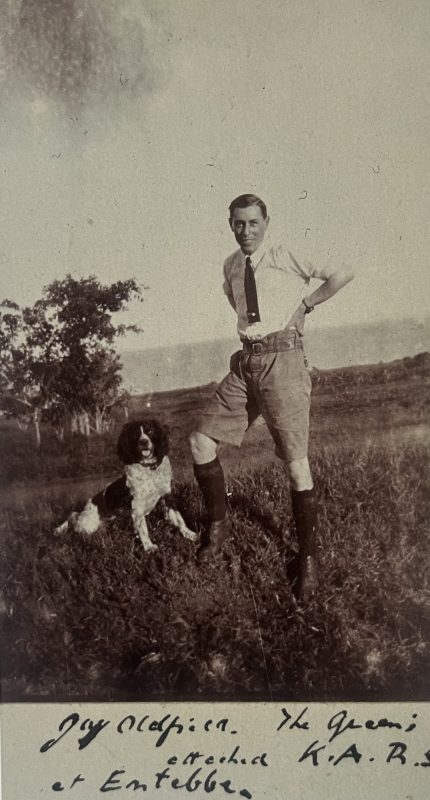

Maude commissioned a huge posthumous portrait of Guy by Ernest Carlos who also painted many other members of the family and who himself was to be killed fighting in France in 1917. The rummage through the tin boxes produced the discovery, in a photograph album belonging to Guy’s first cousin Fred Oldfield, of a tiny (two inch by one and a half inches) black and white photo taken in Africa and on which, very clearly, Carlos had based his picture: Guy in the same pose, dressed in shorts, though in the picture the background which Carlos has substituted was Kentish rather than Kenyan, and Carlos has given Guy back his moustache. Guy’s little dog, Gib, features in photo and portrait. The Jeffreys arranged for Gib to be brought back to England where he lived with them at Doddington for the rest of his life, indulged by being allowed to lie on Sir Richard’s sofa.

Guy Oldfield and Gib, by Ernest Carlos R.A., 8ft x 5ft, painted posthumously from the little black and white photograph

Guy Oldfield and Gib, 2 inches x 1 1/2 inches, photographed by Fred Oldfield in Africa

Fragments from Tin Boxes by Richard Oldfield is available from the Faversham Society at 12 Market Place and from Top Hat & Tales, 1 & 2, Market Street, Faversham.