Words Sarah Langton-Lockton Photographs Lisa Valder and Hugh Ribbans

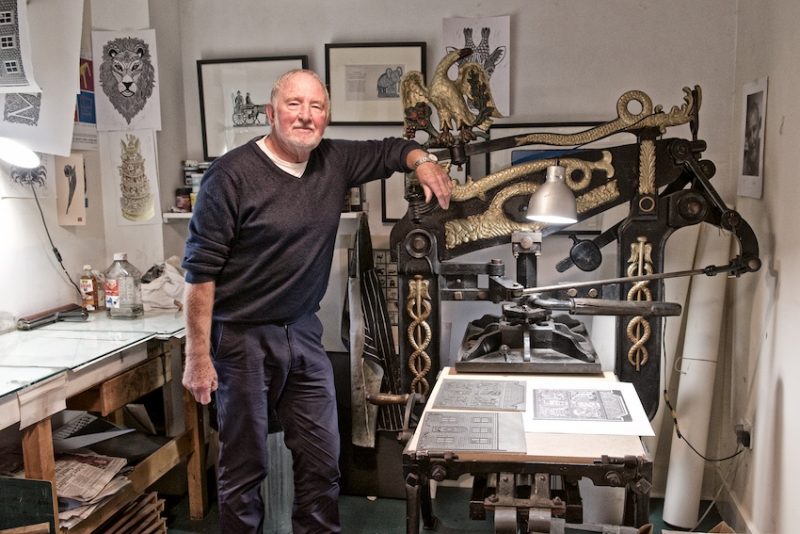

Hugh with his 1860s printing press

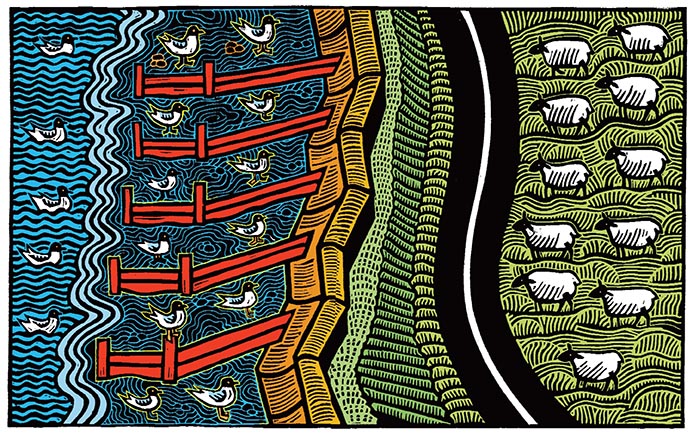

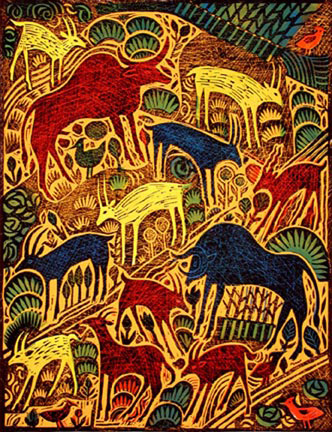

‘I’m obsessed with line, which translates itself into pattern and shapes. I will instinctively round it off – everything I do ends up as a mini design.’ Hugh is talking about the influence of his successful career as a graphic designer on the beautifully composed and executed linocuts that are now his principal artistic activity. He confesses also to the influence of Aboriginal art and a reverence for the work of printmaker Edward Bawden, both evident in his own work.

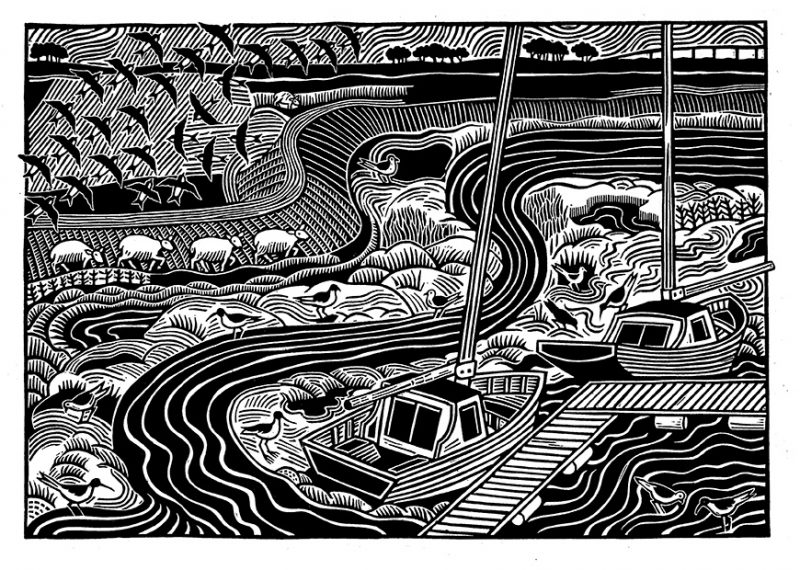

Conyer Creek

Seasalter seagulls – an obsession with line, which transfers itself into pattern and shapes

We are sitting at a scrubbed pine table at the kitchen end of the long, light-filled living room on the first floor of Hugh’s white, weather-boarded house at Conyer Quay. The front of the house looks out onto Conyer Creek, a tidal inlet flowing off the Swale. Here was once a boatyard for the sailing barges that carried yellow stock bricks from local brickfields for the building of Victorian London, returning with fire ash, bottles and pot lids for the brickmaking process.

Wild things

The ledge for having a cup of tea, or working, while watching out for birds

Powerful binoculars at the ready, Hugh is on constant watch for the seabirds for which Conyer and the coastal marshes are famous and which feature prominently in his work – cormorants, curlews, Great Crested Grebes, avocets, swans and Bar-tailed Godwits. Hugh has built a shallow ledge along the inside of the front window. He can sit here with a cup of tea or do some linocutting, and at the same time ‘start seeing things’. At the back of the house, the kitchen looks out onto a hay meadow, where we catch a small flock of whimbrels pecking at the grass. ‘There are lots of birds passing through,’ says Hugh.

Prints are on every surface in Hugh’s house

One of Hugh’s ground-floor workrooms

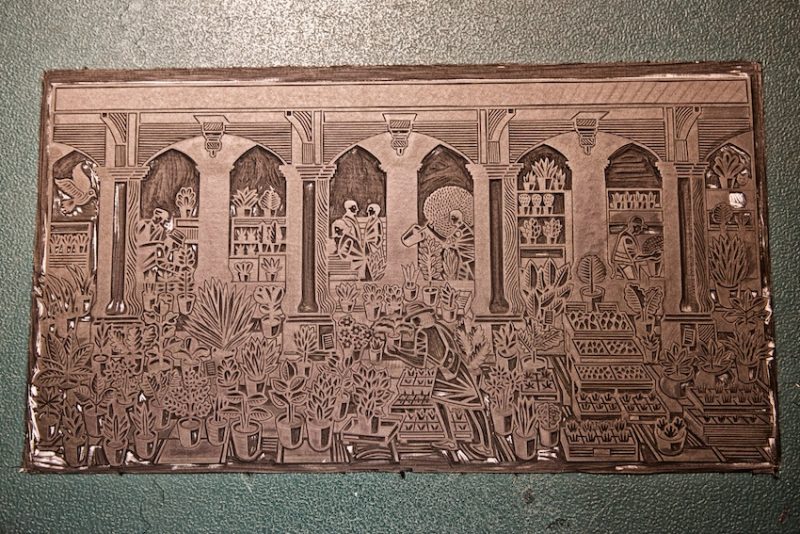

The linocut of Richard’s plant stall, ready to print

Downstairs, the three rooms all serve as workspace; one houses his restored Victorian printing press. Hugh’s work is everywhere in the house – framed and hung on the walls, in piles on surfaces, hung up on pegs to dry. Recent work includes a portrayal of Richard’s popular and densely stocked plant stall at Faversham’s Charter Market. Another striking recent linocut shows a cormorant, wings outspread, on top of a high pole. Beneath the bird flows the sinuous creek. On this, up and down, fish travel at speed while seabirds line the banks. It is a wonderfully enjoyable work, rich in detail embellishing strong central motifs.

A cormorant commands the Creek

Now in his mid 70s, Hugh was born in a nursing home, now a private house, in South Road. His mother came from a farming family and his father worked in a shipyard. The work was hard and primitive and poorly paid. The family lived in a rented house in Westgate Road, near the Rec. ‘I luckily passed the 11+,’ says Hugh. ‘It was probably one of the biggest things that happened to me in my life. My parents were very serious about it – I was the first one in the family to go to grammar school. I do remember the day the letter came, and the relief on their faces.’

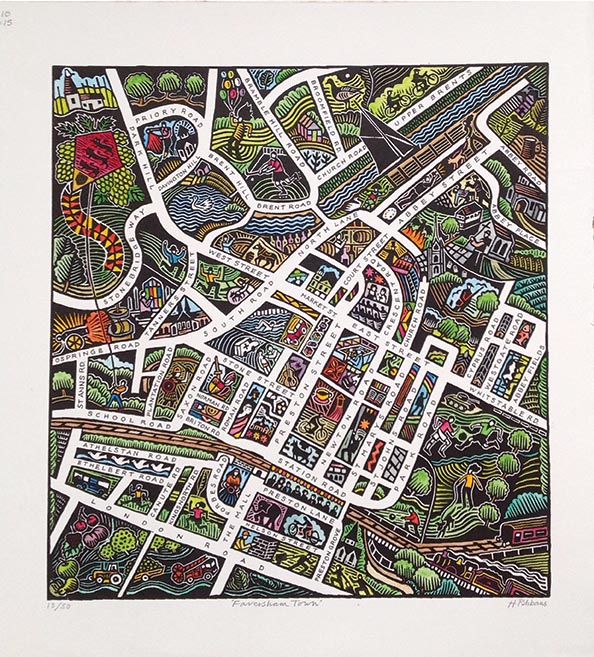

Map of Faversham, showing features from the past and present

At Faversham Grammar School, Hugh had a good art teacher and displayed talent. Following his father’s wishes, he applied to become a police cadet in Maidstone, but was disqualified when diagnosed with red/green colour blindness. This apparent setback proved to be his next life-changing event. ‘I was quite fed up for a while,’ recalls Hugh, until one afternoon the art master let slip that he was going to win the art prize, and said: ‘If you want to go to art school, go to the Canterbury College of Art.’ This was the Sidney Cooper School of Art, a purpose-built art school in St Peter’s Street. ‘When you go for interview,’ added the art master, ‘tell them you want to be a graphic designer,’ a term unfamiliar to Hugh at the time.

Making a linocut

Linocutting tools

He embarked on an old-fashioned, four-year course, doing two years of everything – composition, perspective, life drawing, clay modelling and copying works of art. ‘It means I can draw a bit,’ says Hugh. Linocutting was included, but Hugh didn’t pursue it after college. He says his art school experience was character building – ‘ There were 12 students in my year, 10 of them girls. They had all studied art at A level; I had only done an O level. I was scared stiff and it took me about three years to get any good at it.’

Hugh recalls the Faversham of his student days: ‘It was a much harder town when I was growing up. Teddy Boys commandeered the Market Place from about 5pm. I used to play football with many of them, so although I was a namby pamby college boy, I had a right of passage.’ At the end of Hugh’s course, London beckoned. ‘I got a foothold on the ladder of commerce in an advertising agency in Holborn. I worked my way through various agencies – you have to learn your commercial trade.’ By 1974 he felt he had learnt enough to go freelance. Work poured in. In 1989 he bought a Columbian printing press made in 1860. It is on this press that he still makes all his own prints.

The ink roller used for printing

There were regular trips to Faversham while Hugh’s parents were alive; he moved back permanently around 2000 and has lived and worked in his house in Conyer for seven years. On the scrubbed pine table where his grownup son and daughters once ate their meals is a small wooden box of linocutting tools – V tools, gouges and a thimble to protect the index finger from constant pressure. ‘You have to have a steady hand,’ says Hugh. The left hand, which holds down the lino, is the most important (if you cut with your right hand). ‘It gets very strong, as once you start cutting you don’t want the lino to move.’ The creative process Hugh likens to what athletes call ‘getting in the zone.’ ‘I do rubbings all the time to see what I’ve cut. Quite often I don’t remember doing it.’

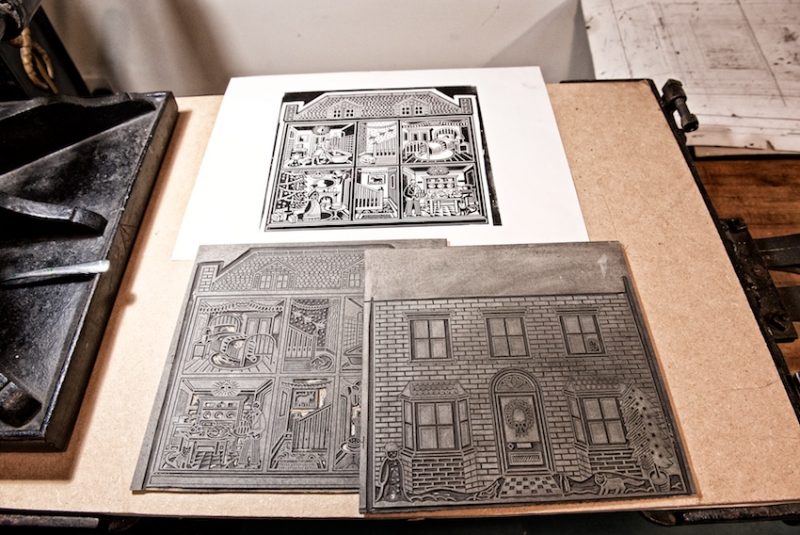

Awaiting printing, below, the finished article, above

Hugh says: ‘I’m not a graphic designer any more, I’m a printmaker,’ but he still undertakes commissions to which he has taken a fancy or to support a charitable cause. An example is the logo he designed for the inaugural Faversham Literary Festival held in February this year – a young woman or man (there are two versions) absorbed in a book while perched in the upper branches of an apple tree. The image is striking and stylish and was instrumental in inspiring confidence in this new event. As Hugh said to the organisers, ‘People will take you seriously if you look right.’

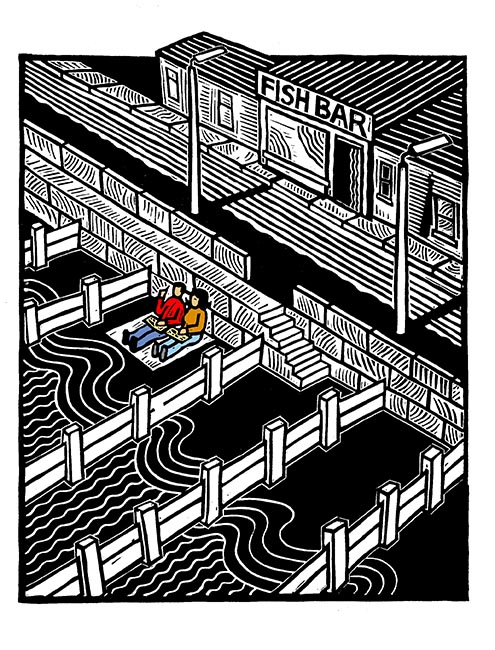

Fish and chips

Hugh is engaged in an exciting new venture. He is one of five successful winners of commissions, each worth £2,500, offered by the Devon Guild of Craftsmen to artists born before 1948. The commissions are for a new contemporary craft work responding to the theme of age and change within the artist’s lifetime. Hugh will make four linocuts portraying the four stages of his life – in Faversham, then Canterbury, London and latterly Faversham and Conyer. The work will be shown in an exhibition, A Good Age, at the Devon Guild in 2019. ‘The aim,’ says Hugh, ‘is to encourage older people to carry on doing it.’ He cites the example of Edward Bawden, ‘who did a linocut in the morning and died in the evening.’

For those of us who love his work, there are fortunately no signs that Hugh is planning to stop any time soon. You can buy his prints online at www.ribbans.demon.co.uk or at Top Hat & Tales in Faversham.

Top Hat & Tales

110 West Street

Faversham

ME13 7JB

Tel 01795 227071