Words Posy Gentles Photographs Jason deCaires Taylor

Changes wrought by the sea and its creatures

We like to scamper and splash around in its shallows, but what of the depths of the sea? As a species, we tend to treat it, on the one hand, as a department store where we can get food and enriching things like gold and lithium; and on the other, as a dump. Most of us just don’t know what it’s like down there.

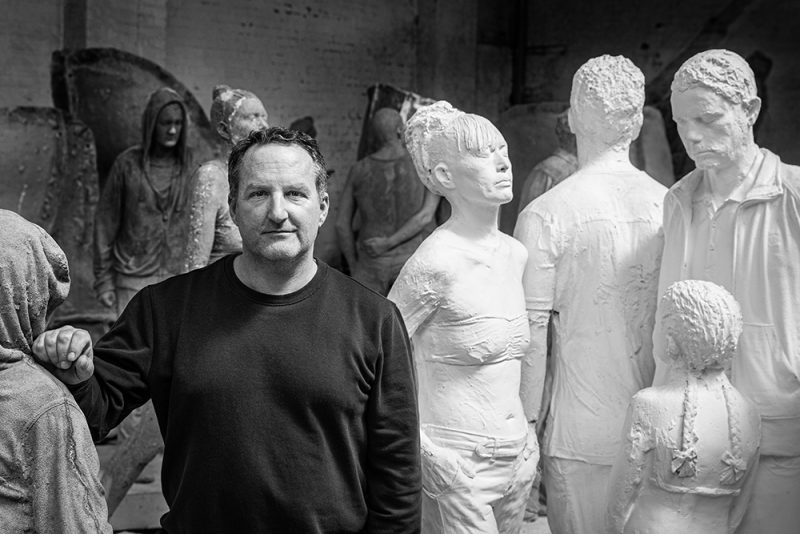

Jason deCaires Taylor knows just what it’s like and through his underwater museums and sculpture parks, wants us to learn that the sea is ‘sacred’ – emphatically not a ‘resource’. Jason is an underwater sculptor, professional underwater photographer, environmentalist and scuba diver. The depths are his natural milieu and, if his job description seems long, it is because each aspect is essential for the creation of his extraordinary body of work.

Jason deCaires Taylor (photo: Neil Brown)

The Silent Evolution: Cancun, Mexico

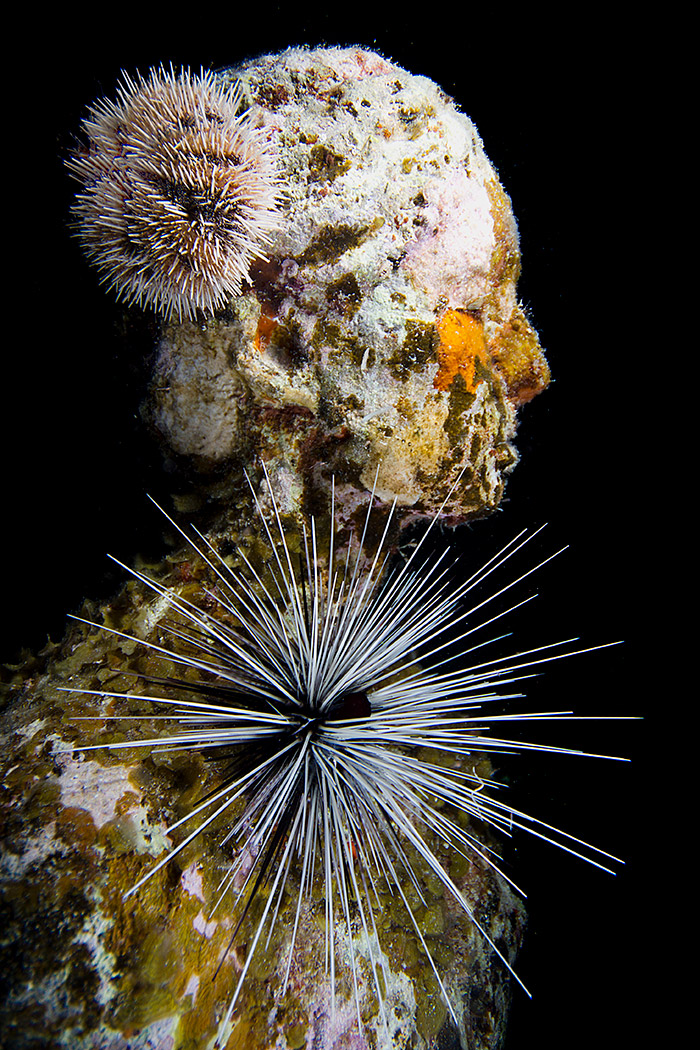

His work is largely figurative, moulding and casting people in his Faversham studio, shipping them around the world and sinking them to the bottom of the sea. Here they stay, eyes closed in an eternal dream, becoming part of the marine ecology. The figures are cast in a long-lasting PH neutral cement, textured to make a stable and permanent surface to allow coral polyps to attach themselves and grow. Once they are in position on the seabed, the sea and its creatures start their embellishments – coral nose and hair extensions, rose-pink cheek patches, elaborate fascinators with wispy veils that sway in the currents. Jason says: ‘The inherent beauty is in the growth, the transformation, which can’t be replicated by humans. The works are always permanent because they’re designed to foster marine life.’

Once in the sea, Jason relinquishes his artistic control – marine ecology takes over

Faversham Life met Jason at his studio near the Creek, on his return from Australia where he had been installing a new series of sculptures called The Ocean Sentinels on The Great Barrier Reef, representing notable marine scientists and their work. It is the third addition to MOUA, The Museum of Underwater Art, Australia and will be officially launched on World Ocean Day, 8 June. The snorkel trail through the museum aims to educate the snorkeller about The Great Barrier Reef, its rich history and links to indigenous cultures and traditions.

Ocean Sentinels is a series of eight sculptures which fuse human figures with natural marine forms. The human figures are predominantly Australians whose work in marine science and marine conservation has influenced our understanding of reef protection

An educational snorkel path through the Ocean Sentinels

Sinking the sculptures

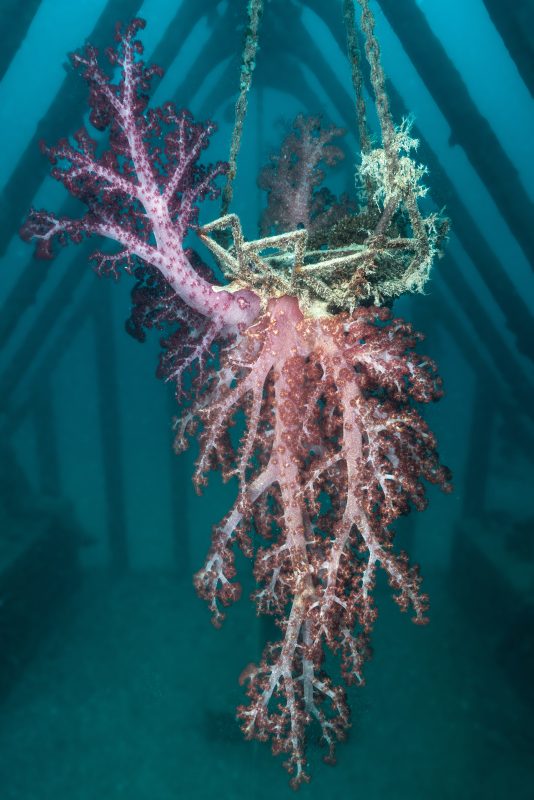

While in Australia, Jason revisited the 2019 installation The Coral Greenhouse. Jason says: ‘My work is like gardening. Things evolve. It’s not instant.’ Since its installation, the underwater greenhouse has become a flourishing underwater garden. Corals, two metres long and weighing around 20kg grow from the hanging baskets. The diversity and abundance of fish attracted by the colonisation of the sculptures by benthic organisms (from Benthos, Ancient Greek: the depths of the sea), have increased fourfold.

The Coral Greenhouse: an underwater garden where corals grow

The Sea-Change: The original cast (below), and (above) after four years in the sea

A hanging basket with coral hanging two metres long. Corals sting to the touch, the surface made of tiny glass-like fibres

With his museums of underwater sculptures in seas across the world, Jason seeks to ‘redefine the underwater world and give it a different iconography, a different definition.’ He explains his use of the term ‘museum’, saying: ‘Museums are places of conservation, education and about protecting something sacred. We need to assign these same values to our oceans.’ He says: ‘Ultimately, the marine life is the museum and the wonder. I just use the sculptures to get the people in. They’re Trojan horses – there’s an ulterior motive.’

Each project is different. The seas and the marine life are different. Colours change as you get deeper and the light is filtered out. Jason says: ‘You have to go very deep for it to be pitch black but you lose colours the deeper you go – the colour spectrum changes. Yellows and reds go first and you’re left with blues and greens.’

Crossing the Rubicon at the Museo Atlantico. Sleepwalking to catastrophe, the dreamlike quality is intensified by the opacity of the water

Jason says the opacity of the water in the Atlantic off Lanzarote affects the mood of the Museo Atlantico. Installed in 2016 at a depth of 14 metres, this was his first sculpture museum in Europe. He saw that the diminished visibility changed the blue colours. ‘It gave a much more ephemeral, dreamlike presence. It wasn’t so clear cut, left a lot more to the imagination and had a very different feeling.’ We see it in The Raft of the Lampedusa, reminding us of the drowning of almost 400 migrants in 2013 attempting to reach Lampedusa by sea. It draws comparison to the 1818 Géricault painting The Raft of the Medusa, but the violence and anguish of the painting, the grappling and the panicking, is not present in Jason’s work. The tragic, resigned figures, eyes closed, sitting quietly and separate from each other, effect such terrible sadness.

The Raft of the Lampedusa

The sea bed is barren around Lanzarote, mostly sand, but the sculptures are attracting marine life. Jason says: ‘Some days, you can’t see the sculptures for all the fish. Then the predators come.’ Angel sharks had been almost extinct in Europe but now live on the sea floor around the sculptures, along with barracudas, sardines and octopuses.

In 2018, Jason made his first cold water sculptures in Norway. He says: ‘I’m not a massively experienced cold water diver, but find those the most exciting now.’ His first impression looking at the fjord was that it looked a bit English – brown murky water, unappealing and freezing cold. But from under the water, it was a different matter. He found ‘a beautiful, fragile habitat’ and when he looked up to the surface, all the leaves and sediment turned the water gold. And as his breath escaped from his breathing apparatus, it collected in tiny bubbles under the ice in giant pools of silver. The sculptures attracted orange glass tunicates, white calcareous worms and shrimps; the fish came, then seals visited the sculptures to eat the fish. Jason says: ‘From nothing, this chain of life emerged.’

Nexus is a work of 12 sculptures located above and below the waters of the Oslo Fjord, designed to draw students towards the diverse marine life in the surrounding fjords

Students will be asked to monitor how the structures develop over time as they are colonised by the sea life

Orange glass tunicates, calcareous white worms and shrimps colonise the cold water sculptures

This extraordinary creative process – combining art, the conservation and creation of marine environments, and the means to educate and introduce people in urban environments to marine ecology – started when all the threads of Jason’s life came together while he was teaching scuba diving in the Caribbean island of Grenada in the early 2000s.

Vicissitudes in Grenada: a ring of children hold hands and face out into nutrient-rich oceanic currents. Cast from children of diverse backgrounds, they are a symbol of unity and resilience

Jason’s parents were English language teachers, his father British and his mother Guyanese, and they lived in the Caribbean, Malaysia and Portugal until he was 10, when they moved to Canterbury. He graduated from the London Institute of Arts in 1998 with a BA in Sculpture and, along the way, had gained a qualification as a diving instructor.

At art college, all his work related to the environment – work that changed according to where it was sited. On graduating, he saw his fellow graduates moving into commercial careers in art, and decided instead to go to Australia to teach diving. He loved travelling. Jason says: ‘I did lots of different of jobs for 10 years. You could say maybe I was quite lost, meandering through life. But I look back and realise I now use all the skills I picked up.’ While setbuilding for a show at the Milennium Dome, he learnt about logistics and handling cranes and weights. In Australia he had a colleague who familiarised him with the plight of the coral reefs, and encouraged Jason to take an underwater naturalist course, learning about marine ecology.

Still meandering, Jason rocked up in Grenada, teaching tourists to scuba dive to earn his daily crab and callaloo, when a hurricane hit the island, damaging coral reefs already suffering from the attentions of tourists. Jason says: ‘I was thinking how to draw people away from the reefs. There was a bay which had been decimated by the hurricane. It had an interesting natural topography with sandy coves and corridors, like a forest with little clearings you could go in to – and I started thinking about art again and creating an artificial reef.’ What followed was the creation of the Moliniere Beauséjour Underwater Sculpture Park – the first of its kind and now listed as one of National Geographic’s 25 Wonders of the World. This summer, Jason’s going back to Grenada to add new sculptures to the park.

Jason’s passion for the deep is innate: ‘I love diving by myself – diving at night, turning my light off to be in water and darkness; sometimes lying on the seabed and closing my eyes. It’s not as silent as you’d think. There’s the noise of fishes clicking, and you’re much more aware of the sound of your breathing.’

At the heart of Jason’s massively ambitious projects is that he wants to remind us where we all came from (the sea) and to change our relationship with nature. He says: ‘Historically, the sea has been classed as a resource from which we can take as much as we want. Fish have been been seen in terms of “fish stocks”, commodities to be extracted, rather than as a delicate marine ecology.’

‘If we were allowed to harvest as much as we wanted from natural rainforests or woodlands or anywhere on land, we wouldn’t tolerate it. But we do tolerate it with the sea because it’s so unknown and removed from our everyday presence.’

A reminder of where we originated

His work is a connection, a reminder that we are natural ourselves: ‘It’s not man versus nature, artificial and natural – we are natural – and we forget that. And forgetting that, we run the risk of finding ourselves extinct.’

Jason’s next challenge is to draw attention to deep sea mining. ‘We’re entering a phase where lots of companies are lobbying for licences to do deep sea mining to extract precious minerals. There are lots of fragile habitats that exist in these places and they’ve developed machines that are basically combine harvesters which roll across the sea bed destroying everything in their path. I’m trying to get a piece called ‘Fool’s Gold’ 2000m deep, but it’s not fully resolved yet. I’ve been trying to find a submarine to place it. There are a few moving parts on that one!’

While sorting that one out, Jason is working on an intertidal sculpture for Whitstable. He is concerned with the plight and politics of our waterways on a local level, as well as globally and, Faversham Life hopes, one day we will see his work, shipped only the 30 yards or so from his studio, in Faversham Creek.

Text: Posy Gentles. Photography: Jason deCaires Taylor

For further fascinating information, photographs and news about all Jason deCaires Taylor’s work, go to @jasondecairestaylor and underwatersculpture.com