Magna Carta and the Faversham Charters at 12 Market Place

Faversham has a truly magnificent series of royal charters granted to the town by successive English monarchs. The earliest dates from the reign of Henry III in 1252, followed by eighteen more granted by 1685. For a town of its size, this collection is one of the finest anywhere in England.

A new exhibition at the Visitor Information Centre at the Town Hall, 12 Market Place now highlights a selection of them, including an example of Faversham’s own copy of Magna Carta ― one of the most celebrated documents in English history ― together with documents, maps and artefacts preserved in the town for many centuries. This is the first time they have been exhibited in a permanent display. The organisers hope that by bringing these extraordinary artefacts to a wider public, new light will be shed on them. They emphasise that while Faversham has a strong tradition of local historical studies, there is still so much more to be learnt.

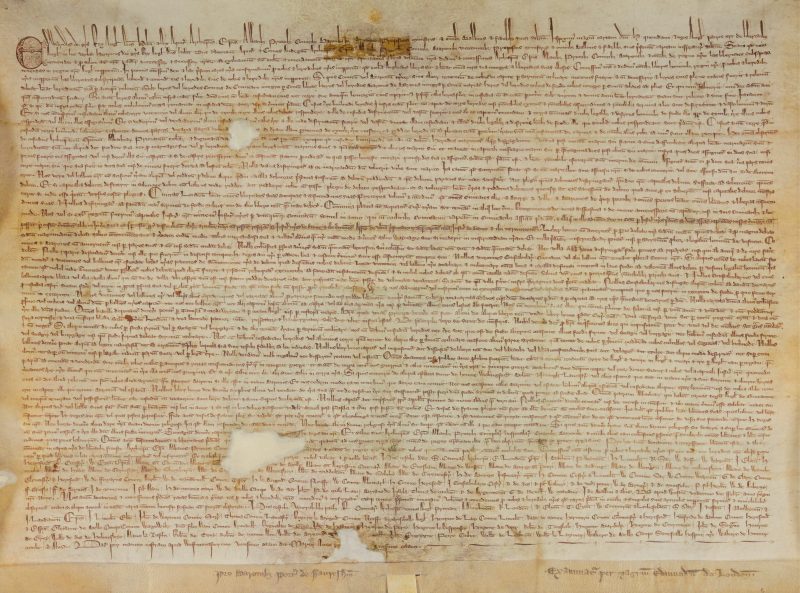

Magna Carta takes centre stage in this dramatic new display. Like the other royal charters on show, Faversham’s Magna Carta is a kind of contract made by a king, setting limits on his power and conceding that his subjects had ancient rights and liberties which could never be taken away. Though Faversham’s example dates from the year 1300, the document was of course first issued by King John to his rebellious barons in the year 1215. Written in Latin on a single parchment sheet it consists of a long series of clauses in Latin defining the limits of royal power. Many were very specific to John’s own turbulent times and have been largely forgotten, but some set out principles of law and government which remain in legal force today.

Faversham’s Magna Carta, from the year 1300

The terms of Magna Carta have endured and have influenced many later constitutions and legal systems around the world, including the British Bill of Rights of 1688 and the Great Reform Act of 1832, the American Constitution and the constitutions of Australia, India and South Africa, among many others. Rightly or wrongly, the charter is revered as a foundation document of liberty, cited by campaigners such as Mohandas Ghandi and Nelson Mandela and it continues to be symbolic of the protection of human rights.

It is not precisely clear why Faversham received a copy of this ‘Great Charter’ from Edward I’s chancery in the year 1300, though it seems that many other English towns obtained one at the same time and that most were subsequently lost or discarded. Edward’s reign was marked by unprecedented debate over the extent of royal government and the common law and towns like Faversham ― long used to claiming immunity from the intrusion of royal officers in their affairs ― would have been especially keen to have written evidence of ancient rights. The town was also embroiled in longstanding disputes with its Abbey and with St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury over their respective jurisdictions and these too may have come to head around the year 1300 – all the more reason to resort to terms of the Great Charter.

Faversham’s earliest surviving common seal, bearing the image of a ship

But the new exhibition is not all about Magna Carta. Also on display is the earliest known document to bear Faversham’s first common seal. Made of black wax impressed with the image of a ship it represents the importance of ships and the sea to the town, but more specifically it represents the ship contributed by Faversham to the ‘ship service’ provided by the Cinque Ports to the crown for the defence of the kingdom. More than 700 years old, this beautiful little artefact is a precious survival.

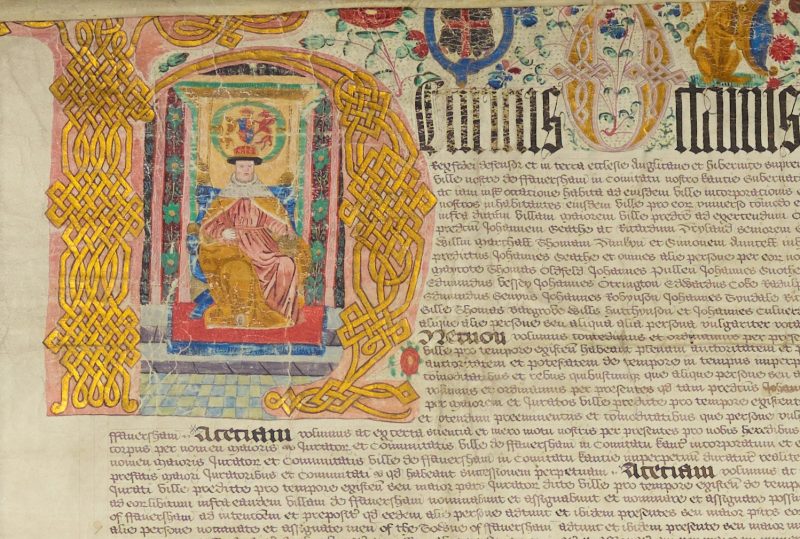

Illuminated initial from Henry IV’s charter to Faversham (1408)

There are also two spectacular illuminated charters, rich in decorative ornament. Henry IV’s charter of 1408 is perhaps the most attractive of all, with its elaborate illuminated initial letter ‘H’ (for Henricus, or Henry), which must have been carried out in one of the illuminators’ shops around the royal Chancery in London. With its scrolling border, rich colouring and burnished gold, it is exquisite and one of the finest of its type.

Henry VIII depicted on his charter to Faversham (1546)

Henry VIII’s charter is dated 27 January 1546, the year before his death, and includes a superb portrait of the king sitting on his throne. It is not known who made this image, nestling within spectacular interlaced borders, but it would be fascinating to study how this image fits into English traditions of royal portraiture.

Faversham’s Burghmote horn (c 1300)

Perhaps the strangest and most outlandish exhibit is Faversham’s common horn or ‘Burghmote horn’ probably more than 700 years old. Blown within recent memory by incoming members of the town council, the horn was historically sounded at the four corners of the town to summon the mayor and ‘jurats’ (forebears of modern councillors) to their courts and meetings. It is a powerful symbol of the continuity of local government, while Faversham’s manuscript custumal book, dating from the years around 1400, is also remarkable as evidence of high levels of literacy and legal savoir faire within the town’s medieval government. Two of the spectacular Oyster Fishery maps, dating from around 1620 (featured in an earlier Faversham Life article) invite us to look closely at the unique geography of Faversham, the Swale and Harty and to reflect on how the town’s place in the landscape has shaped its history and culture to the present day.

All the Faversham charters and artefacts have been photographed and can be seen at the website: https://favershamcharters.org/

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: Neil Brown and Faversham Town Council