Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft and courtesy of The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Oyster shells are everywhere on our stretch of the North Kent Coast, littering the shore from Harty to Seasalter and Whitstable beyond. The oyster fishery was the livelihood of many Faversham families from Roman times at least, and in the medieval period Faversham Abbey controlled the supply of oysters by a royal grant. In 1671 Thomas Southouse wrote in his book about the abbey, Monasticon Favershamiense, that local oysters were ‘most eminent’ and ‘surpass those famous ones of Lucrine’ (the Italian lake thought by the Romans to produce the finest oysters).

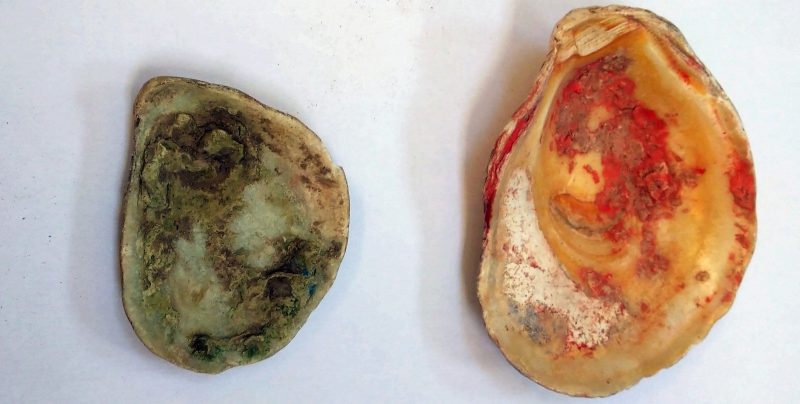

Medieval oyster shells on display at the Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre

But the two discarded shells pictured here should be rather more than eminent. They are usually on display at the Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre and though the museum is currently closed (for obvious reasons) I managed to see them last month, thanks to Heather Wootton, volunteer curator for The Faversham Society.

The largest shell (right) contains a bright vermillion red pigment, the smaller one (left) a greenish-yellow colour, very bright green in a few areas towards the rim. These are traces of paint or, more probably, ink. These traces have been analysed microscopically, showing that the red one is cinnabar (a mercury compound) and the green one probably ground azurite (a blue copper-rich stone) mixed with yellow lead pigment.

The shells were found in 1965 during the excavations of Faversham’s medieval abbey. They had been thrown into a pit along with all sorts of detritus and builder’s rubble some time before the 16th century — at which point the existence of this once immense building was almost entirely erased in the few short years after Henry VIII’s Reformation. Imagining what Faversham Abbey was like has long been a preoccupation and a fascination for me. So little remains, and yet present-day Abbey Street, the creekside and the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School grounds would once have been dominated by the abbey church. Founded by King Stephen and Queen Matilda in the 12th century as a future royal shrine for what they hoped, in vain, would be their glorious dynasty, it was large by any standards. Although smaller than Canterbury and Rochester Cathedrals for sure, it was far larger and more massive than the later church of St Mary of Charity next door or any other building for miles around. The 1965 excavation revealed the footprint of a tremendous cruciform building with towers and cloisters; yet of this Caen-stone building barely the remnants of a gatehouse (now part of the familiar Arden’s House) and traces of some fine large stones used in the walls and footings of a few surrounding houses survive. I’ve often lingered at the entrance to Abbey Place beside the remains of the gatehouse on a summer’s evening trying to conjure in my mind’s eye the the abbey’s West Front in the setting sun, or on a winter’s night picturing its dark silhouette traced by moonlight against the sky. It’s not easy stripping away the streetlights, parked cars and wheelie bins from the scene.

A Benedictine monk: the frontispiece to Thomas Southouse’s Monasticon Favershamiense, London, 1671

Sometimes though, I can just imagine something of the medieval comings and goings, sacred and profane, through the gatehouse into the abbey precincts. I can just picture Cluniac Benedictine monks in black garb praying, singing, reading, writing and working the abbey gardens, but also the constant traffic of produce in and out of the abbey grounds, reflecting the abbey’s other function as landowners and controllers of Faversham’s surrounding farmland and fisheries.

For me it’s sometimes the smallest details that spur the imagination most deeply. To add some colour to our picture of the medieval abbey let’s return to our cinnabar and azurite-stained oyster shells. Similar examples survive, including a couple from London, recovered from Merton Abbey, dated to the 13th century and another from Norwich, equally stained with coloured pigments, red, green and blue. The supposition is that medieval artists, probably scribes preparing small amounts of expensive pigments for decorating manuscripts, mixed them up in convenient receptacles of a hard and smooth material, just large enough to hold a small pool of colour. A recycled oyster shell was just the job, and could be discarded afterwards, as these were at Faversham. Another possibility is that they were used by the artists of wall paintings, as much part of a medieval abbey as decorated manuscripts. But as Heather Wootton points out, if they were for paint, they seem rather small. Barely enough for a medieval matchpot I’d have thought, and I’m inclined to see them as inkwells for writing or decorating manuscripts.

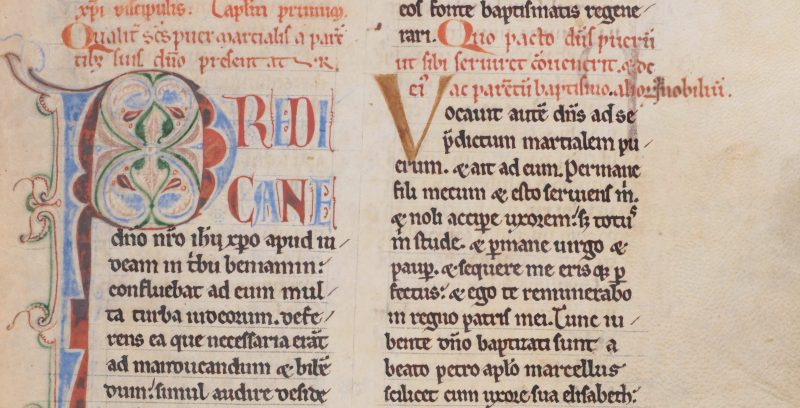

Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 161: Lives of the Saints, f. 2r (detail)

Manuscripts and writing would have been at the heart of an abbey like Faversham. On the one hand, a medieval abbey would generate masses of parchment business documents recording the abbey property and its everyday business, while on the other there would have been religious books for study by the monks — texts of the Bible, commentaries by the Church Fathers and biographies of special saints. We know precious little about Faversham Abbey manuscripts, except that a small handful survived the Reformation and have turned up in other libraries.

The manuscript above was made around the year 1200 and is very likely to have originated at Faversham Abbey. It is a collection of Saints’ Lives, written in Latin recording several English saints including Neot, Dunstan and Swithun. Like other English manuscripts of this period, its script is breathtakingly lovely. The main text is in dark brown ink mixed from oak tree galls — of course written with a carefully cut feather pen. The large initial ‘P’ includes bright green ink in its decoration, while the rubrics above are in red (reminding us along the way of the origin of the word ‘rubric’, literally referring to a text in red ink). These are precisely the colours we see in the traces of our oyster shells and they shine out from the parchment page as brightly as the day they were laid down having been protected for eight centuries between the covers of the book. We may never know if this mysterious and beautiful artefact was actually written at Faversham, or brought in from elsewhere, but the mere likelihood that it was here is spine-tingling. Likewise, we don’t really know how old the oyster shells are (beyond the fact that they are obviously medieval) and we’ll never know who mixed up their cinnabar and azurite in them and what these colours adorned.

Being of a bookish cast of mind, I’m utterly captivated by these fragments of evidence of books in medieval Faversham. There is very little to go on. We know that an abbey like Faversham would certainly have had books, and probably that its monks worked at copying and making books themselves, working in a dedicated scriptorium beside the cloisters. But the cloisters and the abbey library were destroyed at the Reformation, and the books cast to the four winds. We are so very fortunate that we can still look at just one of them and even turn its pages, through digital wizardry: Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge MS 161: Lives of the Saints has been digitized in its entirety and can be viewed here. Together with the remarkable survival of two humble oyster shells they bring colour to our medieval past.

For more on Faversham Abbey, see Faversham in the Making, edited by Patricia Reed, 2018. The excavation report describing the oyster shells is Excavations at Faversham Abbey, Brian Philp, 1965. For the manuscript described here see Early Gothic Manuscripts, Part 1, Nigel Morgan, 1982 or the description in the Parker Library online catalogue (link above).

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: Justin Croft and courtesy of The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge