Words Posy Gentles Photographs Minna Ford

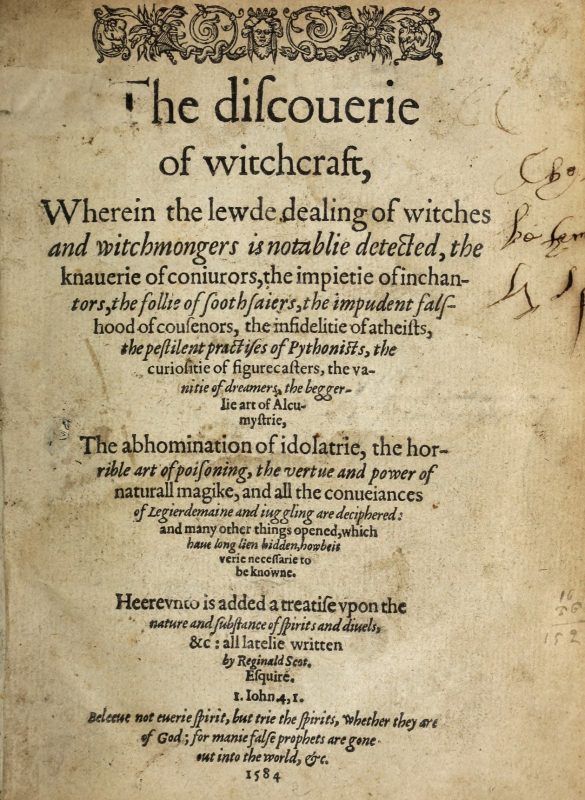

Reginald Scot was born in 1538 at Smeeth in Kent. His fame rests on two publications: The Discoverie of Witchcraft, and another on hop-picking and hop culture

In 1645, a Faversham man Thomas Gardener, fell out of a window suffering considerable pain to his bottom. Mirth rather than sympathy greeted his misfortune and Gardener, perhaps in an attempt to recover his dignity, or perhaps because he believed it to be true, said that the Devil himself had caused his defenestration, and blamed a local woman Joane Williford, for asking him to do it. Whether she had been present and laughed harder than the others, history does not relate, but Joane Williford was accused of being a witch and taken away to be interrogated, a brutal procedure – the details of which can be found elsewhere.

Four women were tried and all found guilty – Joane Williford, Joan Caridan, Jane Hott and Elizabeth Harris – and three were hanged from a tree near the Guildhall in Faversham Marketplace on 29 September 1645. The fate of the fourth, Elizabeth Harris, is unrecorded.

After being found guilty, three of the women were hanged from a tree near the Guildhall

From 1563, when Conjuration and Witchcraft became a statutory offence, to 1735 when the Witchcraft Act was repealed, some two thousand people were tried in Britain as witches, most of them women. 513 of these cases were in the South East, predominantly in Kent and Essex, and of 513 trials, 112 of the accused were found guilty and executed, according to the UK Parliament website.

The case of the Faversham Witches is one of the most notorious, largely because of the account of their confessions, subtitled A True Copy of their Evil Lives and Wicked Deeds, published by Robert Greenstreet, the Faversham Mayor who conducted the trial.

The four women had the misfortune to be tried by an assembly, for whom the existence of the Devil and his works as an explanation of disease and accident were not questioned. Other judges took a more rational approach as is evident in the fact that less than a quarter of those tried for witchcraft in the South East were executed.

Reginald Scot of Smeeth in Kent was one such sceptic. He wrote a highly successful book, The Discoverie of Witchcraft, in which he presented his belief that the country had been fooled into believing in witchcraft by easily explained trickery. Unfortunately, this rational element was largely ignored by his readership who lapped up the lurid details of the belief in, and the practices of witches, alchemy, conjuring and the spirits. It is suggested that Shakespeare’s witches in Macbeth were inspired by his reading of the book. (It is also interesting to note that Reginald Scot’s other successful publication was about hop-picking and hop culture).

No such rationality existed however in the assembly gathered in Faversham by the Mayor Robert Greenstreet in September 1645, or those who undertook their cruel interrogations. Of the women’s confessions, Kelvin I Jones, author of The Witches of Kent, writes: ‘Their reasons for practising the craft [of which they were accused] remain unconvincing and through their words one hears the urgings of the torturer and the threats of the executioner.’

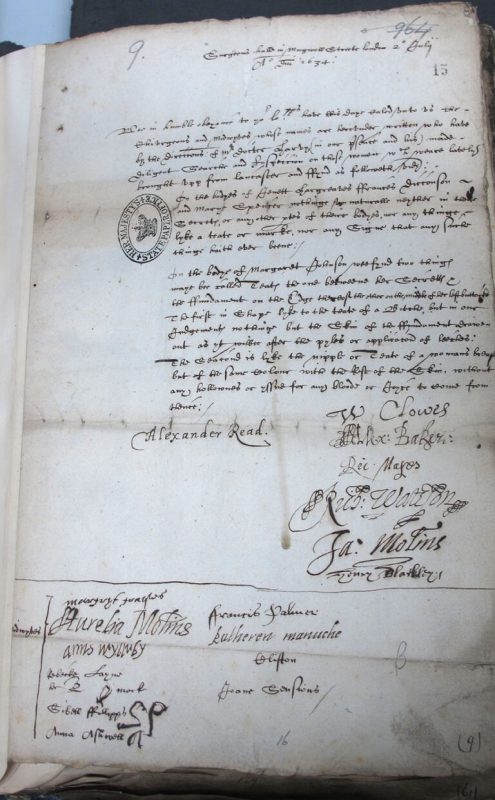

A certificate of the examination of accused witches (National Archives)

Remove the satanic elaborations, and the confessions of the Faversham four have great pathos. Joane Williford, who implicated the others during the interrogation, appears little more than an occasionally resentful woman with a small dog Bunne of whom she was very fond. An affection for small animals was rather damning in the 17th century if you were being accused of witchcraft. Witch hunters called them familiars and believed them to be devils or demons and to suckle on the witches. The identification of supernumerary nipples was a particularly grotesque feature of proving witchcraft.

A witch feeding her familiars with blood, in A Rehearsall both Straung and True, of Hainous and Horrible Actes Committed by Elizabeth Stile (1579)

Some of the confessions are transcribed in The Devil in Britain and America by John Ashton published in 1896. They are rather repetitive, and the spelling erratic as originally written.

Joane Williford confessed: ‘That the divell, about seven yeeres ago, did appeare to her in the shape of a little dog, and bid her to forsake God and leane to him; who replied that she was loath to forsake him. Shee confessed also that shee had a desire to be revenged on Thomas Letherland and Mary Woodrufe, now his wife. She further said that the divell promised her that she should not lacke, and that she had money sometimes brought her, she knew not whence, sometimes one shilling, sometimes eightpence, never more at once: shee called her Divell by the name of Bunne. She further saith that her retainer Bunne carried Thomas Gardler out of a window, who fell into a back side. She further saith, that neere twenty years since, she promised her soule to the Divell. She further saith that she gave some of her blood to the Divell, who wrote the convenant betwixt them. She further saith that the Divell promised to be her servant about twenty years and that the time is now almost expired. She further saith that the Divell promised her that she should not sinke, being throwne into the water and that the Divell sucked twice since she came into the prison; he came to her in the forme of a Muce.’

Joan Caridan speaks of a black rugged dog that came into her bed and spoke to her in ‘a mumbling language’. Jane Hott describes a hedgehog that was soft like a cat.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London

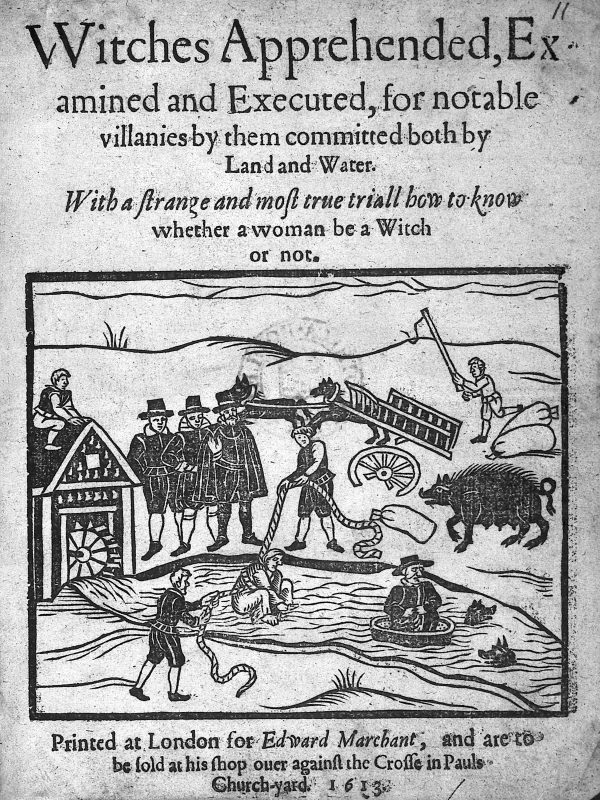

Title page of “Witches apprehended…” showing a witch being dunked in a river.

Witches apprehended, examined and executed for notable villanies by them committed both by land and water (1613)

Jane Hott initially was reluctant to confess so was thrown into the water (probably The Creek) to see if she floated which was seen as proof of being a witch. Greenstreet writes: ‘At her first coming into the Gaole, she spake very much to the other that were apprehended before her, to confesse if they were guilty; and stood to it very perversely that she was cleare of any such thing and that, if they put her into the Water to try her, she should certainly sink. But when she was put into the water it was apparent that she did flote upon the water. Being taken forth, a Gentleman to whom, before, she had offered to lay twenty shillings to one that she could not swim, asked her how it was possible she could be so impudent as not to confesse herselfe? To whom she answered, That the Divell went with her all the way, and told her that she should sinke; but when she was in the Water, he sate upon a Crosse beame and laughed at her.’

There is much more in a similar vein in the confessions of the other women which can be read following the link.

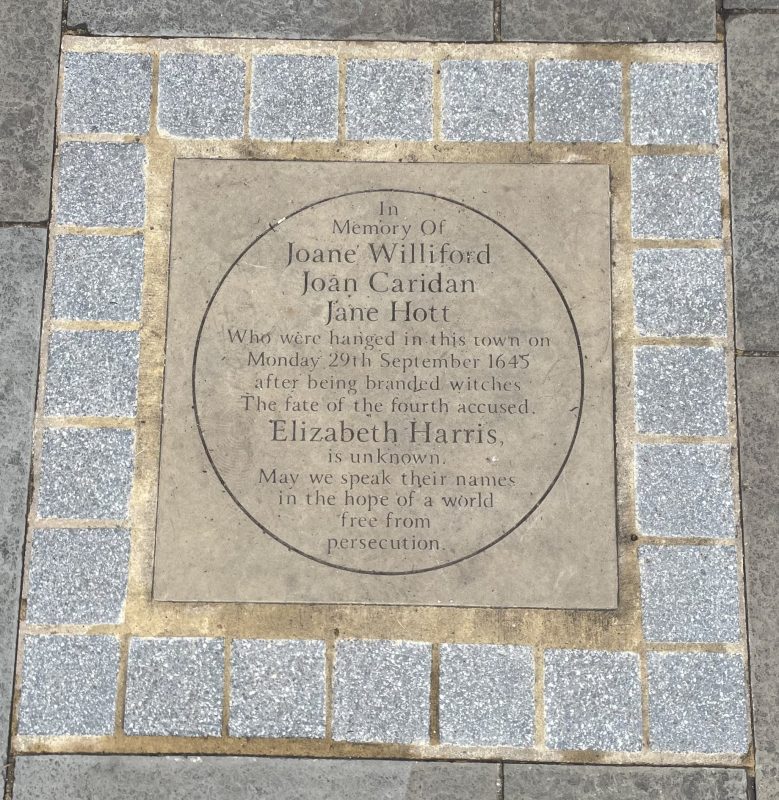

The memorial stone to the Faversham Witches laid near The Guildhall in Faversham

In September 2024, an engraved stone was laid on the site by the Guildhall in Faversham by a more kindly Faversham Mayor, to commemorate the dreadful fate of these four women. It reads: ‘In memory of Joane Williford, Joan Caridan, Jane Hott who were hanged in this town on Monday 29th September 1645 after being branded witches. The fate of the fourth accused Elizabeth Harris is unknown. May we speak their names in the hope of a world free from persecution.’

Text: Posy Gentles. Photographs: Minna Ford