Words Posy Gentles Photographs Various

Novelist Kate O’Brien who is buried in Love Lane Cemetery

Griselda Mussett has always been one to give sleeping dogs a good poke. She has lived in Faversham since 1987 and in that time, as writer, artist and community campaigner, has been a leading figure in Faversham’s cultural life – from writing the definitive book on Faversham’s ghosts to campaigning strenuously against unsympathetic development of Faversham Creek.

Faversham Life spoke to her about her forthcoming book The Invisible Women of Faversham, due to be published by the Faversham Society. Griselda told us that the idea developed after she hastily grabbed a Virago novel from Smiths at Victoria Station for something to read on the train back to Faversham.

It was written by Kate O’Brien, not an author familiar to Griselda. A little research revealed, to her astonishment, that she had lived in Boughton, died in 1974 and is buried at Love Lane Cemetery in Faversham. Kate O’Brien wrote prolifically, and one of her books That Lady, was made into a Hollywood film in 1955 starring Olivia de Havilland. Her 1936 novel Mary Lavalle was scandalous and banned. While living in Boughton, she wrote a regular column for the Irish Times called At a Distance. O’Brien went out of fashion in the 1960s and 1970s, was rediscovered in the 1980s and is now considered one of the major Irish writers of the 20th century. But not in Faversham, because no one had heard of her.

Women of Faversham: The Edward Fagg Monument in St Mary of Charity, erected by his wife and two daughters who figure here

Griselda started to research whether there were other forgotten notable women in the history books of Faversham. ‘There were only really two women mentioned and those in terms of utter hatred – Joan Hatch and Alice Arden.’ Joan Hatch in the 16th century, fought the town council for 40 years to gain her rightful bequest from her husband Henry (See this Faversham Life article for more about Henry Hatch). Alice Arden famously murdered her husband, about which event the play Arden of Faversham was written, and was burnt at the stake in Wincheap with, Griselda believes, her unborn child (see this Faversham Life article for more about the Arden murder).

This panel was made for Henry Hatch, the husband of Joan. Photograph from 1941, capturing all the details of this hard-to-photograph artefact

Alice Arden as a marionette puppet (Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre, Faversham)

Griselda says: ‘Faversham women are spirited, hard-working, funny – I thought they must always have been like this but where was their story.’ She started to rootle around in archives, historical sources and the Faversham Papers published by the Faversham Society and found queens, princesses, benefactresses (do we say that now?), opera singers and holy women.

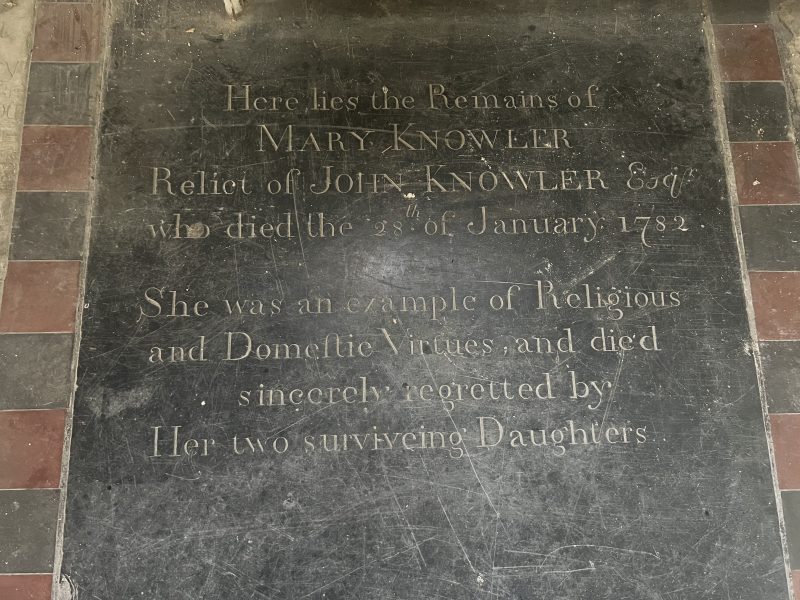

‘An example of religious and domestic virtues’: Mary Knowler, an 18th century Faversham woman

Delightedly trashing a mainstay of Faversham history, Griselda told Faversham Life: ‘It wasn’t King Stephen who built Faversham Abbey – he was too busy enjoying himself fighting battles – it was his wife Queen Matilda (not to be confused with Empress Matilda his rival) and her money.’ The Abbey was a considerable feat, measuring 360ft in length, longer than Rochester Cathedral. Queen Matilda is also historically linked with one of the more visible women in Faversham’s history as, after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538, the remains of the Abbey were assigned to the mayor Thomas Arden who little suspected he was shortly to be whacked by his wife Alice.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Queen Matilda also gave an acre of land between the Abbey and Faversham church and provision for an anchoress called Helmid to live in a small room built on the north side of the church. There is still a cross-shaped squint in the wall of St Mary’s which could date from this time. Griselda says: ‘There’s evidence in the following 80 to 90 years of bequests to anchoresses so Helmid must have had successors.’ Anchoresses were holy women, among whom Julian of Norwich is the most famous. They are distinct from nuns in that they lived among the community in a room attached to the church. However, they were physically separated from the community, sometimes being entirely walled in but for a small window to see the mass in the church, and another to hand out the chamber pot and receive sustenance. Griselda has also found records of an anchoress in Davington called Celestrina. A man could also take on this role, called an anchorite, but women were more popular. With the Reformation, the practice dwindled and eventually stopped.

The squint in the north wall of St Mary of Charity

During this period, Cooksditch Manor as it was then, now a nursing home, was a sanctuary for Henry VIII’s errant sister Mary. She had made a political marriage to Louis XII of France who quickly died, leaving her a 19-year-old widow. Charles Brandon the Duke of Suffolk, was sent to bring her home but instead married her without Henry’s permission – a risky step indeed! They returned to England and waited at Cooksditch while they tried to talk the king round. Finally he agreed to approve their marriage, consoled by £24,000 (£6-7 million) today, the return of her dowry and all her jewels. They became the grandparents of the tragic Lady Jane Grey.

Griselda also discovered that several notable benefactors in Faversham were women. Mrs William Hall of Syndale built the Brents Church in 1881. In 1885, Mrs Townend Hall gave £2000 to build the Cottage Hospital and also bought the garden opposite to prevent the building of houses and preserve the modesty of the patients.

There were musical women. Mabel Herdman Porter, the daughter of Dr Porter whose Tudor house was bombed in World War II and is now the site of Faversham Post Office, wrote songs and musicals in the 1920s which were performed in the town and published as sheet music. Astra Desmond, the famous contralto of the early and mid 20th century, married Sir Thomas Neame of Faversham in 1920 and died in Faversham in 1973.

Astra Desmond, contralto who married Sir Thomas Neame and lived in Faversham

Griselda says: ‘There’s clearly a wealth of stories and I’m not even an historian, just an interested amateur. This is just a first survey.

‘Women’s history is very different from male history – it’s about cooking, fresh water, children and clothing. A lot of my book is about fireplaces. The development of the chimney and later, easy access to clean water, transformed women’s lives.’

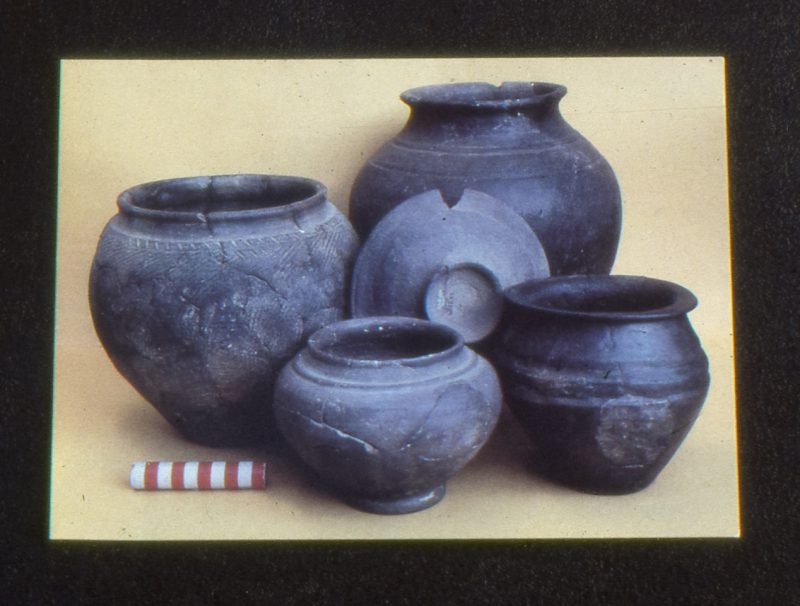

Pre-Roman pots similar to those found in Abbey Farm

The evidence of this development is still very much around us in Faversham today, most visibly the pump by the Guildhall. There is also Copton Mill, the black mill glimpsed on the far side as you turn off the M2 on to the Ashford Rd. Built in 1863 to pump water for Faversham Water Company’s first piped waterworks, it was powered by wind and pumped 10,000 gallons an hour.

This is just a sample of the stories Griselda has to tell and fortunately she will be giving a talk on The Invisible Women of Faversham in August as part of the Open Faversham events. Tickets are available from Open Faversham.

Text: Posy Gentles. Photos: Various