Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft

Most of us have taken solace from our ‘permitted exercise’ during the 2020 lockdown ― from brief forays outside for a walk or a run in March and April, to longer, more leisurely rambles on foot or by bike permitted by the ‘unlimited exercise’ directive issued in May. In these anxious times, the coming of spring and summer has been a source of tremendous consolation. Lots of people have said how much they have enjoyed finding new walks around Faversham and discovering footpaths out into the surrounding countryside. Never has that countryside felt so important.

Orchid and bluebells

The Faversham area is blessed with a rich diversity of plant life and, with quiet roads and clear air, we have appreciated it more than ever before. One family of plants which seems to have done especially well this year are the wild orchids, those uncommon and fascinating flowers which can be found in the woods, meadows and road verges by those with patience and sharp eyes.

As we were told to ‘stay at home’, spring was well underway in the woods to the south of the town towards Painter’s Forstal. A display of bluebells in the dappled sunlight of the woodland floor is always a sight to lift the spirits and dotted amongst them are often the long pinky-purple flowering spikes of the Early Purple Orchid. It is usually the first orchid to bloom (April) and is often quite spectacular. Some British orchids are very rare, but this one is thankfully still quite numerous. In the woods around Faversham, you might catch sight of it without having to leave the footpath.

Early purple orchid (Orchis mascula)

As April gives way to May, the White Helleborine Orchid can occasionally be found, though you’ll have to venture a little further afield — to the hedgerows and verges around the Faversham Golf Course and Wilgate Green. Completely different in appearance to the Early Purple it has much larger creamy-white flowers and tends to hide itself under low beech tree branches in chalky soil. This is quite rare, but again can be observed every year with a bit of patience. Later in May, come the Common Spotted and Pyramidal Orchids which can be seen at Spuckles Wood nature reserve near Stalisfield (Kent Wildlife Trust).

Lady Orchid (Orchis purpurea)

Other KWT reserves further afield are well-known orchid habitats. Yocklett’s Banks, near Waltham (Canterbury) has had majestic Lady Orchids this year – named after their masses of pale pink/white flowers looking like Victorian ladies in crinolines and bonnets. Butterfly and Twayblade Orchids also appeared, along with the mysterious Fly Orchids, which are solitary and retiring plants with deep purple flowers looking very like a large fly.

White Helleborine Orchid

(Cephalanthera damasonium)

In fact the ‘fly’ is an astonishing example of evolutionary natural selection, in both appearance and fragrance, which lures male digger wasps in search of mates to feast on the flower’s secretions who then (unwittingly) cross-pollinate the flower with its neighbours.

Fly orchid (Orphrys insectifera)

Unsurprisingly, Charles Darwin became obsessed with the mechanisms by which orchids were fertilised and reproduced. After observing orchids for many years at Down House (near Orpington) he wrote an entire book on their reproduction, a major contribution to his theory of evolution. Darwin was the most famous natural historian to study orchids in Kent, but Faversham itself has had its fair share of botanists.

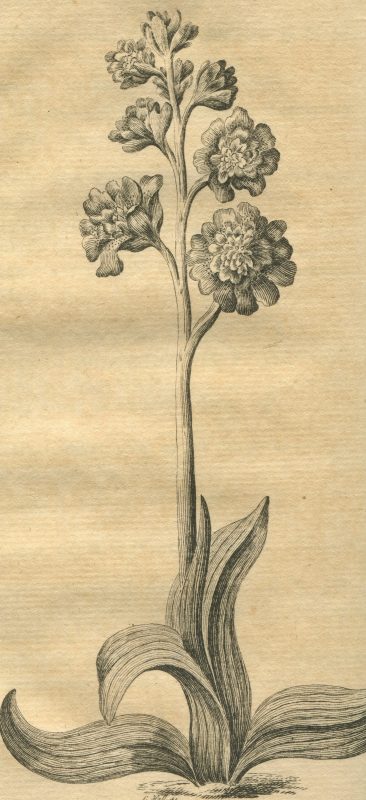

Edward Jacob (18th century surgeon, mayor and antiquary) who lived in Preston Street (his house is now the Spice Lounge) wrote a book on the plants of Faversham in 1777, called Plantae Favershamiensis: a Catalogue of the more perfect Plants growing spontaneously about Faversham. He lists at least seventeen different orchid species, mainly in Ospringe and Syndale.

From Edward Jacob’s Plantae Favershamiensis (1777)

In the 19th century, Faversham was home to a remarkable flower artist, Jane Elizabeth Giraud, who published three popular flower albums illustrated with her lovely hand-coloured lithographs. Her Flowers of Shakespeare (1845) includes a perfect illustration of the Early Purple Orchid (or ‘Long Purple’ as it was called by Shakespeare) as part of Ophelia’s garland from Hamlet.

Quietly observing Faversham’s orchids this year has been a real tonic. They are just a small part of Kent’s rich botanical heritage, which often seems threatened on every side by pressure on land for development. Of Jacob’s 17 species in 1777, only a handful survive. Some of the Kent orchid species are now classified as ‘threatened’ or even ‘endangered’ and it would be a tragedy to lose any more of these exquisite plants.

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: Justin Croft