Words Matthew Hatchwell Photographs Bob Gomes, Sarah Cuttle, Matthew Hatchwell

The Westbrook and Cooksditch are just two of the dozen or more streams that flow from the underground chalk of the North Kent Downs into the Thames Estuary along this stretch of the coast between Graveney and Bapchild. The springs from which they flow have been sources of fresh water for thousands of years and are one of the features that attracted early settlers, and the Romans, to this landscape.

The Friends of Westbrook and Stonebridge Pond meet monthly to maintain and protect this valuable chalk stream

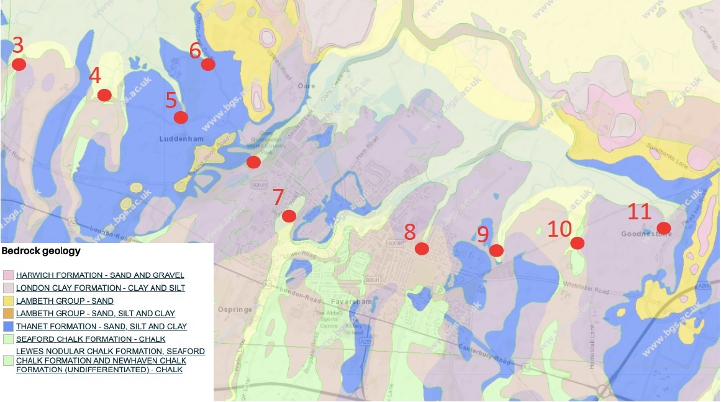

The Westbrook and Cooksditch in Faversham are part of a line of springs that flow from the chalk aquifer along this stretch of the North Kent coast (Graphic by Matthew Hatchwell. Map: British Geological Survey)

There are roughly 325 chalk streams in the world, 275 of them in England and the rest in parts of northern France with similar geological formations. Because of their global rarity, and the fact that such a high proportion of chalk streams occur in England, they are frequently referred to as England’s equivalent of tropical rainforests. In recognition of their special status, chalk streams have been designated as a priority habitat for protection by the British government under its Biodiversity Action Plans for over 20 years.

The bridge and dry lake bed in Lorenden Park were once close to the source of the Westbrook in the valley below Painter’s Forstal

The water in chalk streams is naturally filtered as it passes through the porous rock before emerging through natural springs. As long as it hasn’t picked up too many chemicals along the way (pesticides and fertilisers are a growing concern as levels of phosphates and nitrates in the water increase), it is so pure that it can be pumped almost without treatment into the domestic water supply. It is also slightly alkaline, emerges from the ground at a constant temperature regardless of the season, and – under natural conditions – flows at a fairly steady rate all year round because of the vast volume of water held in the underground aquifer. Unfortunately that has changed since the 1950s as the result of water abstraction for human use, with the result that there is much less water in our chalk streams than there used to be historically. Another problem may be the high volume of water draining out of the aquifer through the flooded gravel pits at Oare and into Oare Creek.

A glass eel recently arrived from the Sargasso Sea – one of the iconic species characteristic of this area

Chalk streams in their natural state are characterised by gravelly beds, which are the result of their typically steep gradients and fast flow that prevent the accumulation of silt. Their unique combination of features results in a particularly rich fauna and flora which, in the case of north Kent streams, probably included trout and salmon in the past as well as the critically endangered European eels and other species that persist today.

A kingfisher: another of the iconic species characteristic of this area

As a priority habitat in the UK, chalk streams should be treasured and protected. That is the goal of local voluntary groups like the Friends of the Westbrook and Stonebridge Pond and Friends of Cooksditch. The reality, however, is that these rare ecosystems have been badly neglected and mistreated for decades. Water quality is poor in both Cooksditch and the Westbrook as the result of Combined Sewage Outflows that discharge raw sewage into these precious environments whenever heavy rain threatens to overwhelm the outdated infrastructure.

Clapgate Spring to the east of Faversham is one of the eight streams in the SERT survey that would have originally flowed directly into the coastal marshes

In the hope of having them inscribed on the national registry of chalk rivers held by Natural England, the Friends of the Westbrook recently commissioned a study by the South East Rivers Trust (SERT) of 11 streams flowing from the chalk aquifer along the north Kent coast in and around Faversham.

The South East Rivers Trust study examined 11 watercourses in and around Faversham to assess their claim to chalk stream status

While all the streams studied were confirmed to flow from the chalk aquifer and therefore to possess most of the qualities of chalk streams, only three – including the Westbrook – had the gravel bottoms that indicate a relatively steep gradient and qualify them as ‘high-confidence’ chalk streams for inscription on the Natural England database. The other two are the stream flowing from the Thomas a Becket (or Bacca’s) spring in Bapchild and a short stretch of the Downs Well stream at Deerton Street.

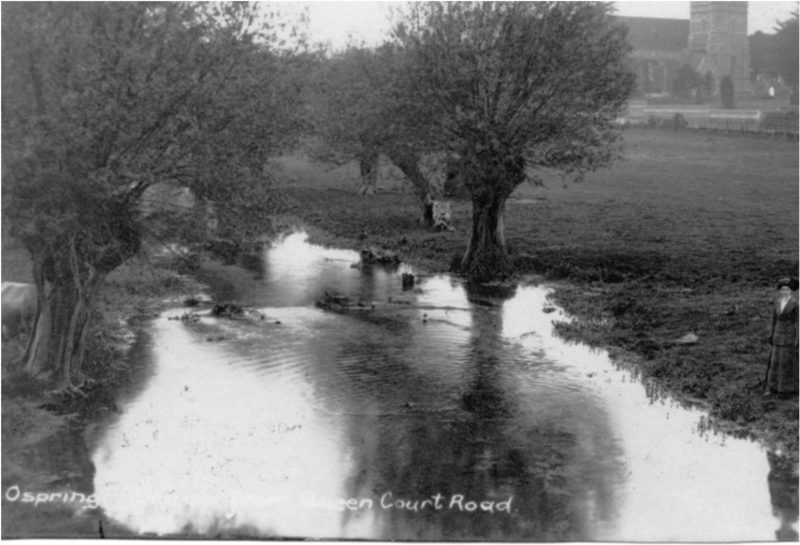

The Westbrook south of Ospringe was a substantial stream until abstraction and other factors caused water levels to drop in the 1950s. Note Ospringe church in the background (Photo: The Faversham Society)

The remaining eight streams in the SERT study – along certainly with many smaller ones that are less obvious in the landscape – all flow from a single spring-line that follows closely the ancient threshold where the chalk of the North Downs meets the marshes of the Thames Estuary. The channels that carry their water today – including from Clapgate and School Farm springs east of Faversham, and others to the west – are therefore the product of the drainage of the coastal marshes by humans since the Middle Ages. There are few if any gravelly sections in these streams, which flow slowly for the most part through low-gradient, man-made, heavily-sedimented ditches that do not qualify as natural chalk streams even though they share many of the same characteristics. The SERT report suggests that, in the past, these alkaline springs flowing directly into the coastal marshes may have formed a calcareous fen, a peat-like habitat now even rarer in the UK than chalk streams, and therefore strengthens the case for the future restoration of the tidal marshes.

While distinguishing between ‘man-made’ and ‘natural’ in a landscape that has been so profoundly shaped by humans over the millennia might seem an arbitrary distinction, the bottom line is that all our streams are valuable and none should be treated like open sewers.

All too often, polluted runoff from streets and fields ends up in the underground aquifer or in surface watercourses. Abstraction from boreholes in the chalk aquifer inevitably reduces the flow from nearby springs, which has a direct impact on water quality in the associated streams. Overall levels of abstraction must fall for chalk streams to thrive. Urgent action is needed too to stop the discharge of untreated sewage into streams like the Westbrook and Cooksditch even under storm conditions.