Words Posy Gentles Photographs William Ford and the David Zwirner Gallery

The Grumpy Girl: ‘Unflash, not projecting, just ontologically there’

Hidden under another canvas in Rose Wylie’s studio is The Grumpy Girl. She is blue, heavily outlined and featured in black, and she glares at you under black brows. There is a belligerent kink to her leg. Rose says: ‘She’s unflash, not projecting, just ontologically there – the opposite of what everyone is looking for in the stereotypical girl.’

Rose Wylie in her studio

Like Rose, The Grumpy Girl strikes the defiant aesthetic position and Rose is delighted with her. She has a dream project. The Grumpy Girl will be made in bronze just as she is, blue and black, flat, but 100 feet high, and stapled with industrial staples to a Zaha Hadid building, one of the long, low, white, sinuous ones. The strong, vertical Grumpy Girl will usurp the upward, masculine thrust with barely a glance at the curvy, feminine building at her feet. Rose says: ‘There would be no confusion as to whose work is whose. It’s an entertaining and arrogant idea but I mean it.’

The work of British painter, Rose Wylie, is now so admired across the world that maybe the project will be realised. She is 85 and has been meteorically successful in the past ten years, having resumed painting and drawing seriously in later life. Last year, she received an OBE, and in 2014 was elected a senior Royal Academician. She has work in private and public collections including Tate Britain, the Arts Council Collection, Jerwood Foundation, Hammer Collection, and York City Art Gallery. This is a mere smattering of her credits and achievements and a visit to Google will elicit yards more information where you will find she has been interviewed by Alan Yentob, photographed by Mary McCartney and raved about by Germaine Greer who ‘wrote a brilliant bit in The Guardian which was rather helpful’ after seeing Rose Wylie’s work in the 2010 Women to Watch exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC.

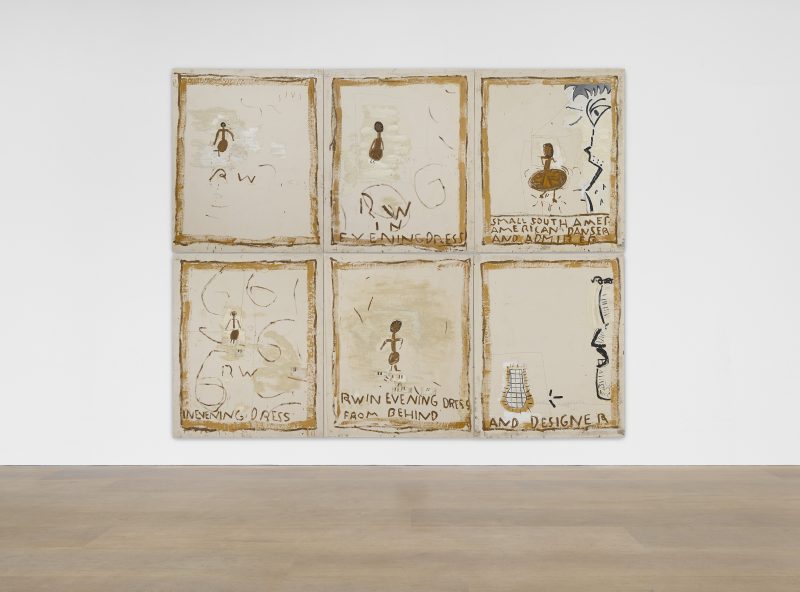

Drab Ant Work – RW in evening dress 2019 ©Rose Wylie. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Rose Wylie is represented by the David Zwirner gallery with currently a solo exhibition in Hong Kong called painting a noun . . . , the show Rose Wylie: Let it Settle at Vero Beach in Florida, and Rose Wylie: endlesslyinappropriate, a series of prints, on David Zwirner Online.

Faversham Life visited Rose in the 17th century red-brick house in Newnham where she brought up her three children with her husband, the artist Roy Oxlade, who died in 2014. In the last spit and bluster of Storm Dennis, Rose showed me around her garden. Roses have rocketed to the top of the trees and luxuriate there supported by gnarly stems as thick as your arm, to be viewed from the hill behind the house and the upstairs rooms. The early, soft, ferny growth of cow parsley covers the ground and its haze of flowers and the lush, green ground elder, yet to emerge, will reign after the snowdrops and primroses withdraw. Rose says: ‘I don’t like mean, tight situations. I don’t like domination. I like ideas rather than nationhood.’ She is talking politically but you see it in her garden and in her paintings as well.

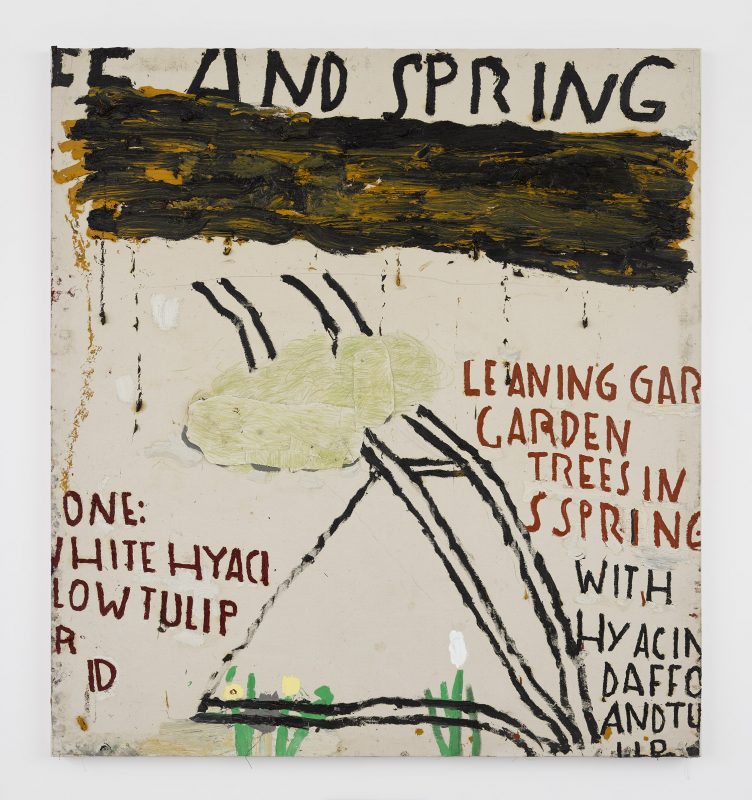

Leaning Trees in Spring 2019 ©Rose Wylie. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

The Newnham garden

The permanence of iced buns. Rose says they stay the same despite having been sitting there for some time

Her work is expansive. She works on large unstretched canvases stapled to the wall and is not controlled by the limitations of an edge. If the painting grows, she will stick on another bit of canvas which gives the paintings an exuberant uncontainment. Jeff Lowe, the renowned sculptor who lives nearby, says: ‘Rose paints like a sculptor. She works from the inside out, building up, sometimes collaging, overlapping and over painting, to arrive at the finished work. If you begin with the rectangle, the work is defined before you even start.’

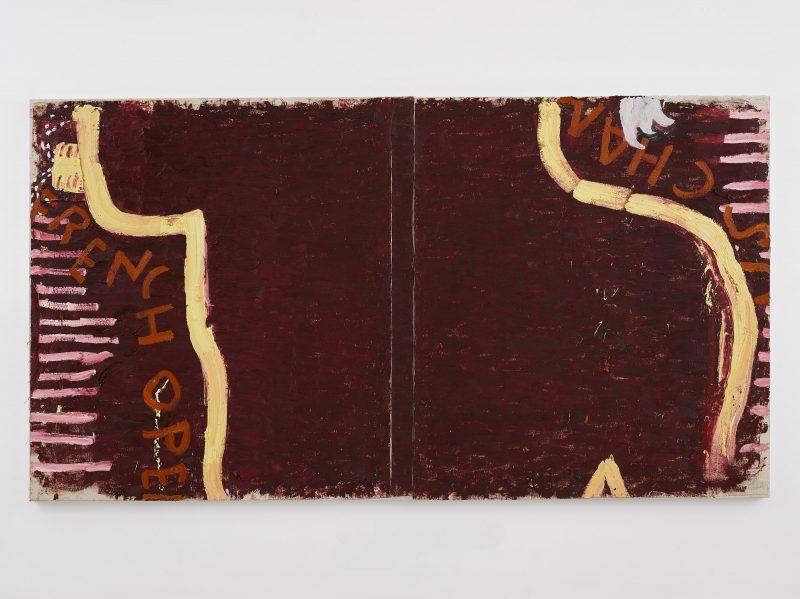

Canvases are stapled to the studio wall

Serena (2019) is a portrait of Serena Williams, painted after the French Tennis Federation harrumphed about the postpartum black body suit she wore at the 2018 French Open – notwithstanding that she wore it to control blood clots caused by her recent pregnancy, and maybe because she looked like a powerful goddess. The torso is painted with dense brush strokes, outlined with a golden glow, and in the top corner there is a nipple spraying milk. Rose says she thought the body still looked too ‘mean and meagre’, so she cut the canvas in half and added another strip down the middle to give it greater breadth.

Serena 2019 ©Rose Wylie. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

The addition is clearly visible. Rose flaunts the process of her painting. Finger marks, spatters and drips, even footprints as the huge canvases are laid on the floor of the studio, are all permissible. There is no tidying up, no neatening of edges. When a painting is to be stretched for sale or exhibition, canvas strips are glued under the sides of the work so that no part of it is tucked away.

The studio

She is cheerfully against artistic preciousness. ‘I like biros, hard pencils and cheap copier paper. They are available to everyone. I like Stanley knives, staples and glue and I don’t like waste and throwing things away.’ Her legendary studio is astoundingly full of crumpled newspaper, rather like a nest – ‘Not just old newspaper,’ says Rose. ‘There’s last week’s Observer here.’ A sloping scree behind where Rose is painting, is presumably formed as she hurls used paper over her shoulder. The skirtings and plug sockets are baroque with brilliant oil-paint tumuli, and amongst the newspapers lie two single shoes gorgeously encrusted. The much-used staple gun is marbled smooth with handling.

A swimming woman in the painting, I’d Like to Be Under the Sea, is stapled over The Grumpy Girl when I arrive. One sees that, despite the apparent simplicity of the figure, there is a feeling of the rolling movement of the crawl; the foreshortened arm, the turn of the head, the twist of the hips and the little gasping dark red mouth. Rose says it took her ages to get the mouth right. Her studio is ‘a place of exhilaration and liberation’. She can paint until four in the morning if she likes, or work while a leg of lamb cooks in the oven downstairs.

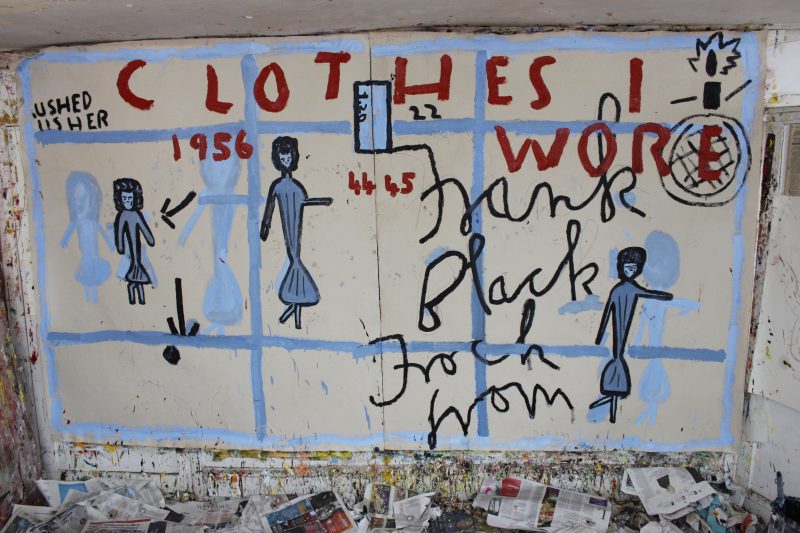

Rose’s life has been long and her memories inspire paintings. She has made a series of works based on a Frank Usher dress she bought in Oxford in 1956 which can be seen on this David Zwirner link. The dress was ineffably glamorous (strapless, black, and bubble-skirted), cost her a month’s wages and she never found a reason to wear it. The Grumpy Girl is perhaps the nemesis of the Frank Usher dress. Pinned to her dining room wall, a canvas shows doodlebugs floating in a yellow sky painted from her memories of living in Bayswater during the Blitz.

Memories of the Blitz in Bayswater

Yet, she has a huge appetite for current and popular culture – footballers and Kate Moss’s pants are not beneath her notice. In her paintings, Rose filters from her ever-replenishing stock of images and ideas from films, art history, newspaper cuttings, literature and the environment. She is working on illustrations for a new edition of The Tempest, drawing in hard pencils on copier paper: ‘It’s all about exploitation and colonialism’. Rose also paints and draws from life. She shows me a familiar image of a high ponytailed girl plugged into her earphones who sat opposite her on the train, and Pete’s Rat, painted and collaged on copier paper. Pete is the handsome cat who was rescued and brought to Newnham after a car accident in Islington. Rose says: ‘There is no message in my paintings; my paintings are the message.’

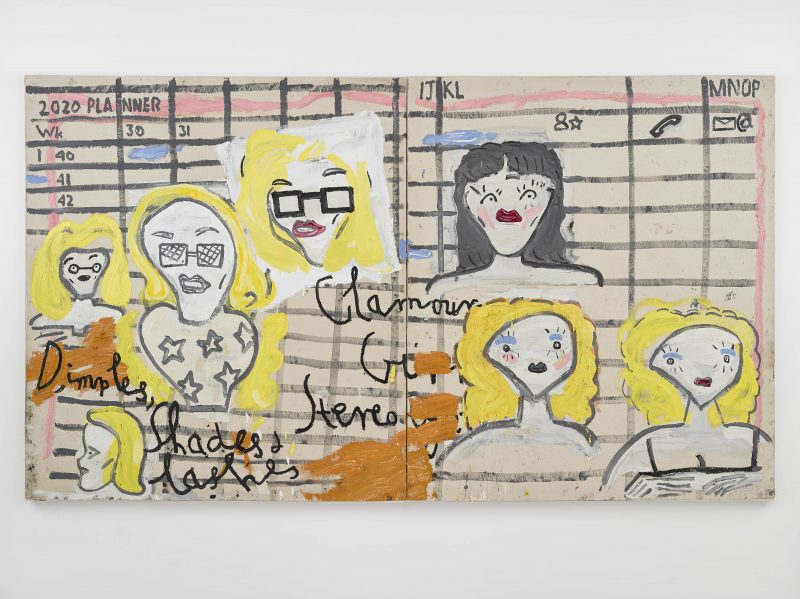

Glamour Girl Stereotype, Shades and Lashes 2019 ©Rose Wylie. Courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner

Rose waited until her children grew up before concentrating on painting and drawing and has no qualms about this: ‘If you’re an artist you have to be very caught up with what you’re doing.’ She says: ‘The age thing was difficult – at the moment they like the artist to be young – but you can get through it. Art is the best thing for coming back to; you just need a pencil and a bit of paper. You don’t need vast equipment unless you’re Anish Kapoor.’

Text: Posy Gentles. Photographs: William Ford unless otherwise attributed