Words Justin Croft Photographs William Ford and Justin Croft

Lo

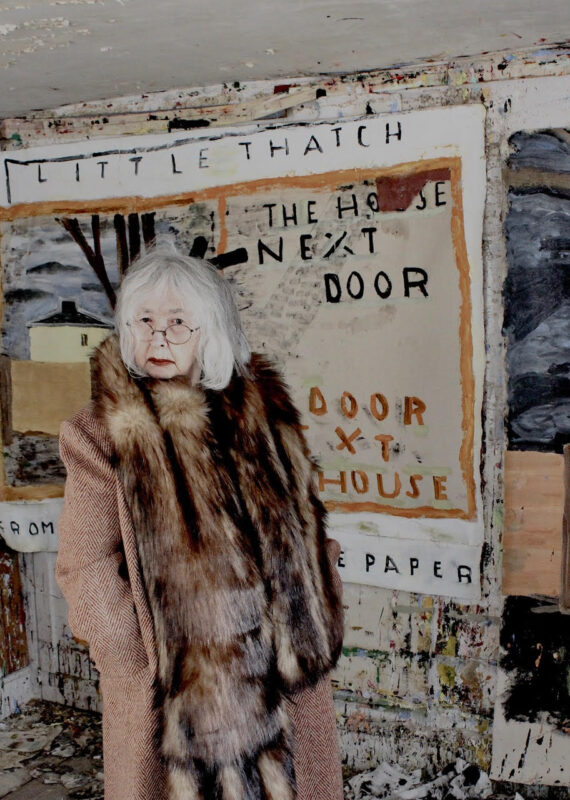

Rose Wylie in her studio January 2026The Royal Academy invites us to ‘meet the rebel painter of the British art world’ on its webpage for the forthcoming exhibition of the work of Rose Wylie. The show opens in February 2026, but the artist is an old friend of Faversham Life (see our 2020 interview) and we are impatient to know more. I made contact with her and was fortunate to visit her Newnham house and studio.

‘Why have they sent you to talk to me?’

Wylie is accusative (playfully, I hope, though I can’t be certain). This is my first meeting and I’ve admitted, sooner than I had intended, that I don’t know much about contemporary art and that I’m not sure I understand it.

It is a cool morning, and I have arrived punctually by bicycle from Faversham. We are standing in her stone-flagged dining room. Wylie is finishing her morning tea and has not had time to light the log fire in the brick inglenook. She soon does, and as the flames leap around hardwood logs, a conversation has already been kindled by her gently provocative questioning.

Rose Wylie, at the age of 91, may well be a rebel, but she is also one of Britain’s most singular and respected painters. She is looking forward to a major solo exhibition at the Royal Academy: The Picture Comes First (28 February-19 April 2026). It’s a tremendous accolade but also a just tribute to a lifelong artist whose career really began when she was in her fifties, after bringing up a family. Her instantly recognisable large canvasses have been shown around the world and reproduced and discussed in articles, while her engaging conversations on art have enlivened the internet for several years now. Represented by the global gallerist David Zwirner, Wylie’s work also holds a robust place in the contemporary art trade.

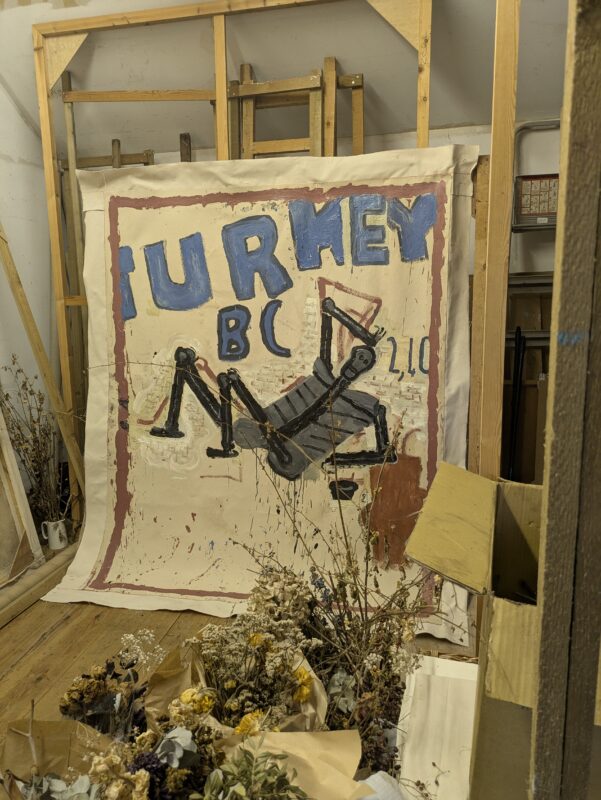

Rose Wylie. Umber Dots

Wylie leads me through a kitchen to the first of her studios, a large space with double doors opening onto an overgrown garden. This is not a work room, but a place where recently completed paintings are stored. I’m unprepared for what I see. A large rectangular panel stands head high on the floor. I’m told it is actually two parts of a triptych, and the third panel, apparently only partially mounted, leans against timber frames to the left, behind masses of bunches of dried flowers and other vegetation in paper cones. I feel I am looking at something very ancient and yet, at the same time, blindingly contemporary. The artist explains that the images take inspiration from a recently discovered Roman mosaic at Antakya (Antioch) in Turkey of which someone had sent her pictures from the internet. There’s a figure running towards a plinth surmounted by a sun and moon, and then an inviting full-sized chair painted from two perspectives at the same time. Wylie is excellent talking on the subject (and subjectivity) of perspective, reminding me of the ancient Egyptian habit of depicting figures from more than one point of view at once and mentioning her love of the early Renaissance painter Fra Angelico. My instinct is to try and decode the images and the surrounding words, but Wylie is insistent that the picture is about form and colour as she sees it. The picture comes first. Any interpretation is secondary.

Rose Wylie. Black Skeleton.

The third piece of the triptych is still separate and shows a cheerful skeleton from the mosaic, reclining happily with one arm at rest — on the head of the footballer Ronaldinho. It’s a contemporary detail somehow in keeping with its antique source, and typical of Rose Wylie’s omnivorous appetite for subjects, which have included Elizabeth I, Nicole Kidman, Marilyn Monroe, Serena Williams, and Snow White.

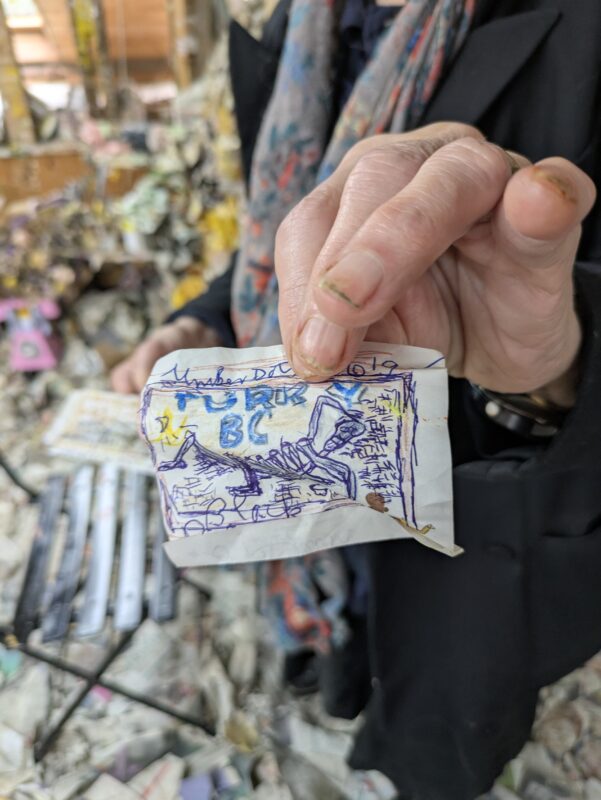

Rose Wylie. Black Skeleton. Drawing.

I’m lucky enough to see an initial sketch for the skeleton panel. It’s a crumpled piece of everyday paper, barely larger than the back of a cigarette packet, the image and text in blue biro embellished with coloured pencils. Wylie says she’s not precious about many of the materials she uses, except for her oil paints, supplied in tins (not tubes) and proper art coloured pencils. Her paintings are done on large, unstretched and mostly untreated canvas, making their surfaces uneven and sometimes undulating when they are mounted on wooden frames for studio viewing.

She’s down-to-earth about the process of painting and sets herself apart from self-conscious painters, past and present, working in elaborate studios with assistants. She refers to them more than once as the ‘big boy’ artists, and I get the idea. On the contrary, she says she’s ‘making pictures’ not ‘doing art’. She formerly painted kneeling on the floor (before hip replacements made it impossible) and she compares that to the graft of women’s work, not far removed from cleaning the oven. It’s a good image, drawn from her experience of raising children and keeping a house in the last part of the last century, but she resists presenting her work as some kind of domestic art. She can treat the same themes as the ‘big boys’, just without the fuss. ‘Cleaning an oven is futile, anyway,’ she adds. Meet the rebel painter of the British art world.

Rose Wylie’s studio

Artists can be awkward talking about their work or uncomfortable discussing methods and inspiration, but Rose Wylie is not one of them. ‘I want to show you this,’ she says, and leads me back through the house and up the stairs to her first-floor studio. This is the space where she still works for long hours every day. I’d seen pictures of this room, and it has become something of a celebrity in itself, featured in both art journals and design magazines. But I’m discouraged from writing about it, as a distraction to the pictures which I’ve come to hear about. We sit down on folding chairs, face-to-face with an arresting new work.

Rose Wylie. The House Next Door.

The subject seems rather closer to home. She explains: ‘It looks like a straightforward domestic narrative, and in a way it is. The subject is the sudden new sight of the house next door, appearing into what had been my isolated top-garden … seclusion had morphed to open-plan (because the small trees and shrubs of the boundary had been cut down for a new fence) to a painting. But the point of the painting is something else — the combination of colour, the bark-like realism of texture on the bigger tree, the coming-together of seen and sensed perspectives, the discrete references to other artists and things — how it’s painted, the painting itself, not what it refers to, but how it is. And then, onto a different level, there’s a perceptual jump into a new idea or subject altogether, from an objective drawing of The House Next Door to a monumental object painting, a jumbo meat cleaver. That is, the whole left canvas becomes the blade, while in the right canvas, the pink fence becomes the handle: a nod to Wittgenstein’s ambiguous duck-or-rabbit image’. We go on and we talk about the meaning of boundaries, borders and identity. She points out a detail on the far right which looks like a flag on a pole, but she insists it’s not ― it’s the corner of her house on the end of her fence.

Rose Wylie. New Paintings.

There are more pictures to see, and Rose Wylie is generous with her time and her thoughts on painting. The real-time narrative on her own pictures is inspirational and precious, but our conversation has also covered Raphael, Fra Angelico, El Greco, Rembrandt, Cezanne, Jacques-Louis David, Henri Rousseau, the African-American artists Sam Doyle, Tschabalala Self and Kerry James Marshall, Pre-Columbian art, Islamic Hajj painting, ancient mosaics and life in a Kentish village, all subjects which have illuminated this artist’s experience. It has been a bracing couple of hours, which has led me to understand something of contemporary painting and its place in the continuum of art history. It has also taught me simply to look properly at a picture before leaping to conclusions and interpretations. Most importantly it has whetted my appetite for the upcoming Academy show. I won’t have the benefit of Rose Wylie’s own commentary but I know it will convey the same vigour and freshness of approach.

Text: Justin Croft. Photography: William Ford and Justin Croft