Words Posy Gentles Photographs Angela Websdale, Tom Organ, Posy Gentles and others

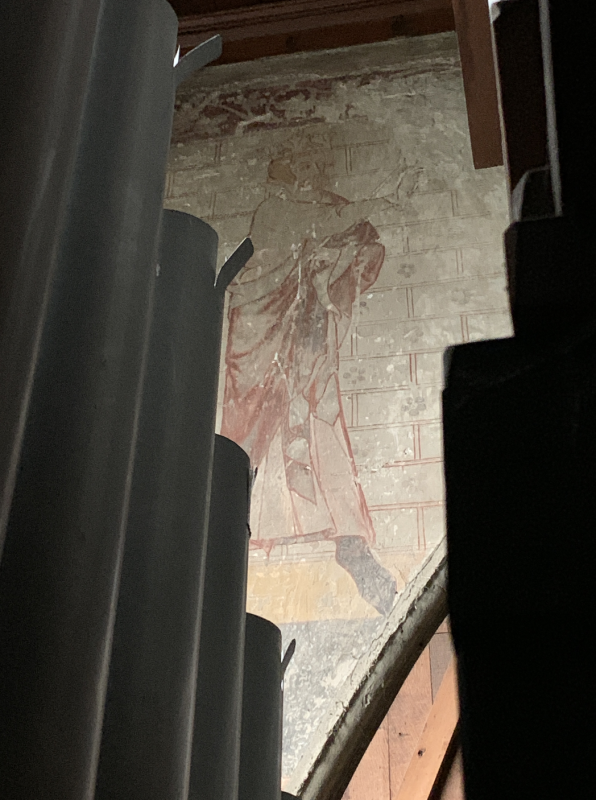

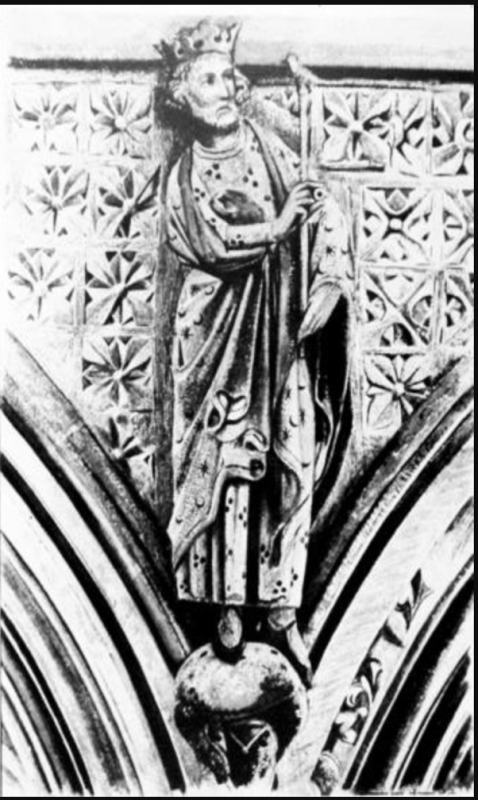

The painting of St Edward the Confessor in St Mary of Charity in Faversham, seen from within the organ

There are paintings dating from the early 14th century hidden behind the organ in St Mary of Charity in Faversham. Dauntless academic Angela Websdale, has climbed on top of it, and crawled beneath it, and seen parts of the painting on the south wall of the chapel to the left of the high altar. Those on the east wall are almost entirely obfuscated by the accursed instrument but for the merest hint of red paint, and all that is to be seen on the north wall is ‘modern’ plaster.

Angela Websdale: turning the received view of the cult of St Edward the Confessor on its head with her PhD Ring the Changes – The Cult of St Edward the Confessor in Kent

Angela’s undergraduate dissertation on the church’s painted pillar, led to a Masters in Medieval Art History. So when the Rev Simon Rowlands, Faversham’s vicar, told her about the hidden paintings, and then Professor Paul Binski, Emeritus Professor of the History of Medieval Art History at Cambridge, visited to talk about what little was then known of them and remarked that the subject needed a PhD, Angela stepped up. So great was the academic interest that Angela’s PhD was fully funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Seven years later, having battled through lockdown and illness, Angela has produced a revelatory PhD, Ring the Changes – The Cult of St Edward the Confessor in Kent. With the discovery of an altar dedicated to St Edward the Confessor in Canterbury, and the examination of the Faversham paintings, her PhD has upturned the view held hitherto that the cult of St Edward was short-lived and notable only in Henry III’s court and at Westminster. She shows that this cult was closely tied to the cult of Thomas Becket and persisted into the 15thcentury. Moreover, Angela discovered the paintings symbolised the end of a violent and bloody century in Faversham’s history, at the very centre of which was St Mary of Charity. Faversham’s hidden paintings are crucial to the story and to understand their significance, we need to know the story of St Edward the Confessor and St John the Evangelist.

Edward the Confessor died in 1066 and was canonised in 1161, after a campaign by Westminster Abbey which, being founded by Edward, may have hoped to gain influence and wealth through his canonisation. To improve his chances, Osbert de Clare, prior of Westminster Abbey, rewrote large parts of the life of Edward commissioned by his wife Edith after his death, so that the rather testy monarch who spent much of this reign dealing with troublesome earls, now appeared all that was saintly.

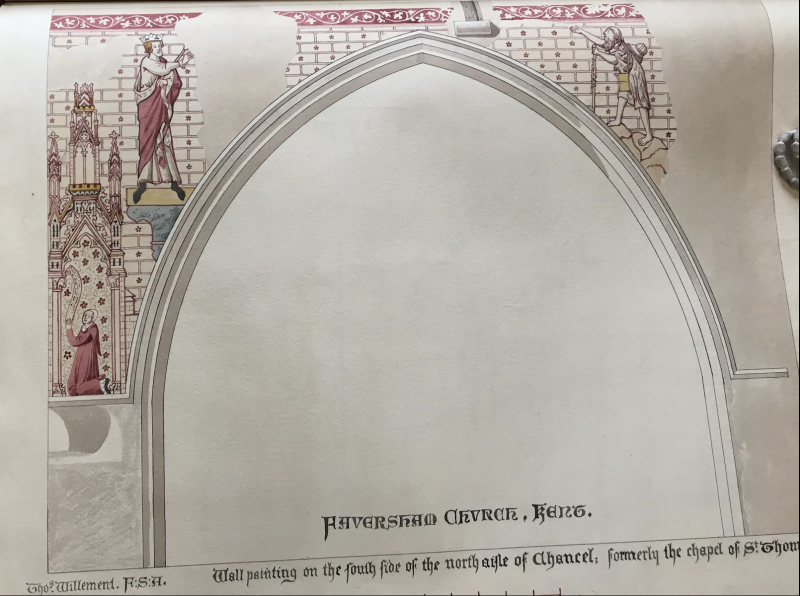

An illustration of St Edward the Confessor’s shrine from La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei. The king’s statue on the far right holds out a ring to the pilgrim St John the Evangelist on the other side of the shrine

This was improved upon again a few years later by Aelred of Rievaulx, who included The Legend of the Ring. The tale has Edward in his latter years with a long silky white beard riding past a church in Essex and being approached by an old pilgrim begging for alms. As the king had just given all his spare cash to the church in Essex, he took the ring from his finger and gave it to the old man. Some time later, two pilgrims found themselves in difficulties in the Holy Land and were approached by the same old pilgrim. When he discovered they were from England, he told them he was St John the Evangelist, gave them the ring and asked them to return it to the king, telling him that in six months he would join him in heaven.

In the 1850s, restorers in the north aisle of the chancel of St Mary of Charity were carefully scraping off layers of whitewash from the south wall of the north aisle. The covering of whitewash dated from the Reformation, when zealous Protestants, paintbrush – or worse – in hand, sought to destroy all decoration associated with the Catholic Church, that could not be packed up and sent to fill the king’s coffers. As the restorers worked, more than 300 years later, a painting started to emerge.

Thomas Willement was living in Davington at this time, restoring the Priory and the church of St Mary Magdalene which had been serving as a stable. One can only imagine his excitement at the discovery as he hared down the hill, watercolours and paper in hand. He was of that 19th century group of Medievalists, who yearned for the values of a pre-industrial age. Willement was called the Father of Victorian Stained Glass and had revived the medieval technique of making a window from separate pieces of glass, rather than painting on glass with coloured enamels. His work can be seen around Faversham today – at Davington Priory and church, and the great window at the Almshouses, originally in St Mary of Charity.

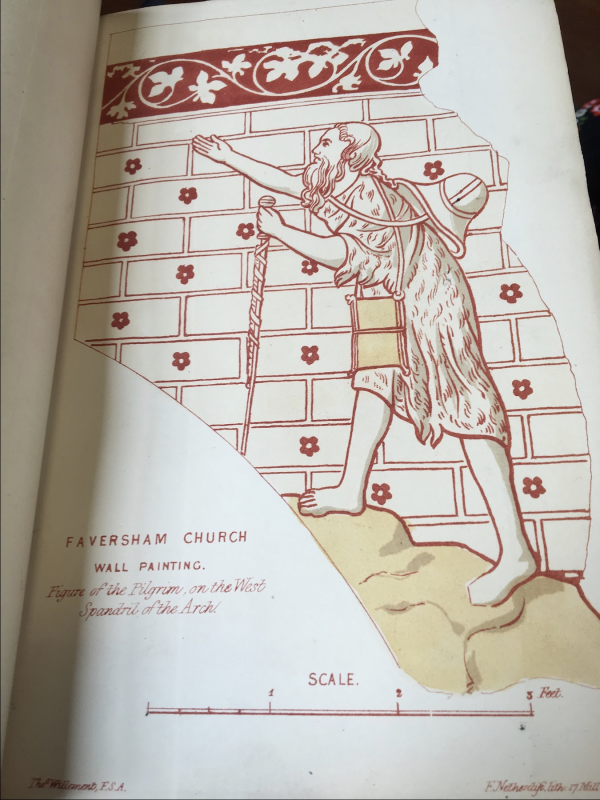

Willement’s reproduction of the painting In St Mary of Charity

Willement recorded the rediscovered paintings in a series of charming illustrations now held by The Society of Antiquaries in London. What he saw was the story of St Edward the Confessor’s Ring. The saint is in ermine and robes, reaching over the arch to hold out his ring to St John the Evangelist on the other side of the arch, who is dressed as a pilgrim, bare-footed and wearing animal skins with a pilgrim’s palm wrapped around his ‘bourdon’ or staff to signify that he has travelled to the Holy Land, and carrying a ‘scrip’ or pilgrim’s purse.

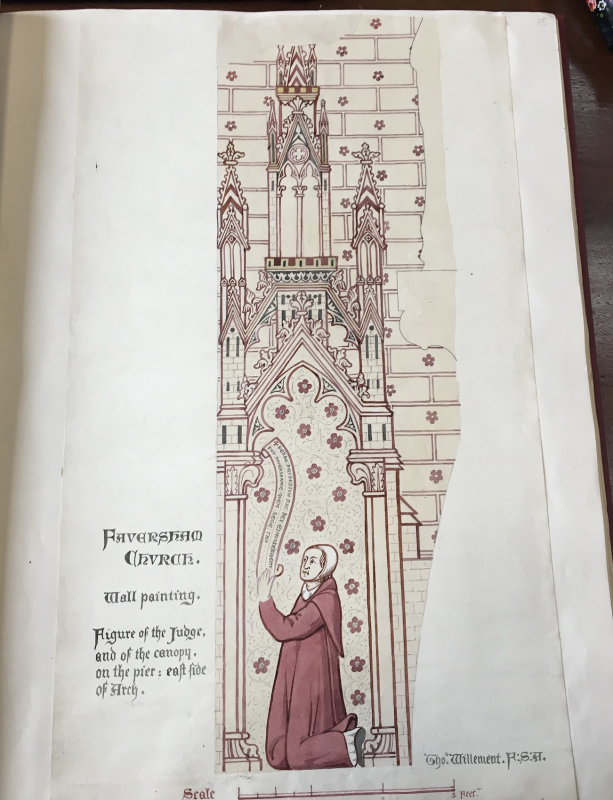

Beneath the king is a kneeling judge in a red robe holding a ‘banderole’ or scroll which translates from the Latin as: ‘O King [Edmund], cause Robert Dod, of Faversham, to bear the crown of Heaven, whom, O pious Thomas, do thou guide.’ (‘Edmund’ should have read ‘Edward’ as the painting portrays, but already the words were becoming illegible as Willement records).

Willement: Robert Dod, the commissioner of the painting and a Jurat in his red robe, kneeling and looking towards the long-vanished altar of Thomas Becket

Angela tells us that the north aisle had been the chapel of Thomas Becket and that the kneeling Robert Dod is looking towards the spot where the altar once stood. We know the altar was there, Angela says, because there are records of medieval wills in Faversham leaving purple damask, a silver chalice and altar cloths to the shrine of Thomas Becket. She says the altar most likely went at the same time as the whitewash arrived. Thomas Becket had challenged royal authority, and was particularly disliked by Henry VIII whose plans at that time included displacing the pope and becoming himself Supreme Head of the Church of England. In 1538, Henry proclaimed Becket ‘a rebel who shall no longer be a saint’.

In the 1870s, more paintings on the north and east walls were discovered, but by this time Willement was dead. There are written records but no images. In 1915, Thomas George Cross, vicar of Faversham, wrote: ‘There was a representation of the murder of St Thomas à Beckett, some of the knights life-sized and in chain armour could be recently traced and were well drawn’.

And then, the astonishing decision was taken to put the organ there, right in front of it, and no one has seen the paintings on the north and east walls since.

Dustsheets protect the organ of Faversham church while work is carried out. The paintings are more inaccessible than ever. Remark how the Victorian painting on the wall replicates the ashlar block of the medieval painting behind

On a frosty morning, Faversham Life met Angela in the church and found, as she had warned, the offending organ draped in polythene dust sheets to protect it from ongoing building work on the church. Angela drew aside the swathes of polythene, revealing surprisingly and bathetically, a pair of black shoes, presumably belonging to the organist, and unlocked a wooden door in the panel. We stepped into the dusty depths of the organ. From within is the closest you can get to the paintings, but frustratingly it wasn’t even possible to look up and see the black pointed toes of St Edward because of the dust sheets. We were so close to the paintings of Thomas Becket on the north wall, unseen for 150 years, but frustratingly all was hidden by the organ.

Paintings could be concealed beneath this blistered and stained plaster behind the organ

Academics, such as Dr Lucy Wrapson, historic paintings expert at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, agree that the paintings in Faversham church are of exceptionally high quality, but the puzzle has been why they are there.

In researching for her PhD, Angela has challenged prevailing assumptions and connected the paintings to Westminster Abbey, reassessed the links between the cults of St Edward the Confessor and Thomas Becket, and their significance to Faversham.

Although, Edward the Confessor had been canonised in 1161, it was not until the reign of Henry III (1216-1272) that the cult really took off. Henry III was a devout believer and the image of The Legend of the Ring featured prominently. In the Palace of Westminster, he had it painted at the end of his bed so he would see it when he awoke. He rebuilt Westminster Abbey, founded by Edward, in the Gothic magnificence that we see today and translated Edward’s body in 1269 to the shrine where it still lies. Henry III chose Edward’s original grave as his initial burial place before being buried beside the saint king in the Confessor Chapel.

A reproduction of St John the Evangelist receiving the ring in The Painted Chamber at Westminster Palace where Henry III slept

The cult of Thomas Becket had grown rapidly – it took only three years from his violent death for him to be canonised in 1173 – and by the mid 13th century, Faversham had become an important stop for pilgrims travelling to Canterbury. In 1243, Henry III ordered an altar dedicated to St Edward in Canterbury Cathedral and prior to that, in c1234, he re-founded the Maison Dieu. The main complex then spread from its present site to the top of Ospringe Rd where the Ship Inn is today. Henry endowed it with wood from his own royal forests, pigs and silver chalices. There were daily masses to St Edward the Confessor which the Canterbury pilgrims would have attended.

Angela has found that the connection of the cults continued after Henry III’s death and did not die with him as had previously been supposed, and that the connection was strong in this part of Kent. In 1272, Henry III’s son Edward Longshanks, became Edward I and in 1285, he presented golden statues of the Legend of the Ring to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury, and in 1307, Robert Dod commissioned the paintings in Faversham Church.

Angela says there was a strong similarity between the painting in St Mary’s to statuary in Westminster Abbey, suggesting that the painters and Robert Dod, the commissioner, were familiar with the work. The painted St Edward in St Mary of Charity is depicted as standing on a carved plinth as is the figure in Westminster Abbey. Furthermore, Angela discovered that there were stone masons working in the atelier in Westminster Abbey with the surname ‘de Feversham’, and when Edward I disbanded the atelier in 1297, surely they returned home and found what work they could here.

EW Tristram’s reconstruction of St Edward from the south triforium at Westminster Abbey

The Legend of the Ring is shown in the statuary in the south triforium of Westminster Abbey. It bears many similarities to the paintings in St Mary’s of Faversham where the painted figures also reach over the arch

So who was Robert Dod? Why did he commission these paintings and why at this time? Angela says he was a corn merchant and his father had been the first mayor of Faversham in 1256. He himself was one of the 12 jurats to the mayor as we can see from his scarlet robe. By the beginning of the 14th century, Faversham had been in the throes of violent conflict for almost a century – at the centre of which was St Mary of Charity. St Saviour’s (Faversham abbey), St Augustine’s and Christ Church were each battling for the rich advowson of Faversham’s church. ‘It was almost a civil war in Faversham,’ says Angela.

Of the many bloody events, these are some of the worst. In 1201, the abbot and monks of St Augustine’s barricaded themselves into St Mary’s to stop King John appointing his own man. The abbot was attacked and dragged bodily from the altar by the sheriff’s men. The contemporaneous Archbishop of Canterbury Hubert Walter said: ‘So horrible and monstrous a deed had not been perpetrated in England since the murder of St Thomas the Martyr.’ A century later, the argument over the advowson continued to be bitter. There were riots in Faversham, the bells were cut down and there was an attempt to set fire to the church. St Augustinian monks armed with swords killed a certain Richard Attwell and attacked Christian de Brendlee who died six days later.

In another vicious act in 1303, the murderous monks of St Augustine set upon Richard Christien, the Dean of Ospringe in Selling. The Calendar of the Patent Rolls described the incident: ‘[They] put him on his horse with his face to the tail and inhumanely compelled him to hold the tail and ride, with songs, and dances, through that town and afterwards cut off the tail, ears and lips of his horse, cast the dean into a filthy place, carried away his writings, muniments and some privileges of the archbishop in his custody and prevented him from executing his office.’

The painting of St Edward in St Mary’s, Faversham

Robert Dod appears to have been instrumental in finding peace for Faversham and in 1307, with a vicar peacefully installed, Dod procured a new bell for St Mary’s and commissioned the paintings of The Legend of the Ring and the paintings of Thomas Becket in the Becket chapel. Scholars have put the two saints at odds – one was a king, the other a defier of the monarchy – yet in St Mary of Charity, the cults were worshipped in the same chapel. Angela suggests that both saints were seen as symbols of peace.

Angela’s study of the painting on the south wall has already challenged many assumptions and she is certain much more could be learnt if the paintings on the north and east walls were revealed: ‘Faversham has a coeval, cohesive scheme of Gothic murals of a quality and style to be found in Westminster Abbey. The rarity and quality of these paintings can’t be understated. We desperately need public support and heritage interest to move the organ.’

Text: Posy Gentles. Photographs: Angela Websdale, Tom Organ, Posy Gentles and others