Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft

It’s not usually open to the public, but we had made arrangements to look at one of its best-kept secrets, a large and imposing west window made by Thomas Willement, who was one of the preeminent artists of the stained glass revival of the 19th century, and spent the second half of his illustrious career here in Faversham. The window is a glorious sight and on a day when natural light was in short supply, the stained glass seemed to generate its own luminosity and colour, an ancient illusion known to medieval stained glass makers and one which Willement sought to revive in his own time.

Faversham Almshouse chapel. West window by Thomas Willement

The central figure is the Virgin Mary, as Saint Mary of Charity, which immediately gives away its original purpose, as one of the great East windows of Faversham’s main parish church. Willement worked on a restoration of St Mary’s in the 1840s and supplied this stained glass window. You can see its civic origins in the roundels at its base: the arms of the Cinque Ports in the centre, flanked by a version of Faversham’s maritime town seal on the left and its three-lions arms on the right. All these are surrounded by truly fabulous gothic ornament – decoration in which Willement clearly took his greatest delight.

The window was moved from St Mary’s to the almshouses in the early 20th century, when a new restoration brought up-to-date (and equally beautiful) stained glass to the parish church, leaving a window spare. Quite how one moves a stained glass window in several parts, made up of many hundreds, perhaps thousands, of tiny pieces, each joined by lead strips is a matter of wonder. Did it come in four large pieces, conveyed on wheels through the streets of Faversham, or was it dismantled fully and boxed up before a complete reassembly in the chapel? Perhaps there are records, or someone took a photograph. We’d love to know.

Willement seems to have taken to Faversham while working at St Mary’s and purchased the then-ruinous Davington Priory in 1845 as his home (of which more later). But before he set foot in the town he had marked himself out as one of the foremost artists and designers of heraldic and decorative glass in the country.

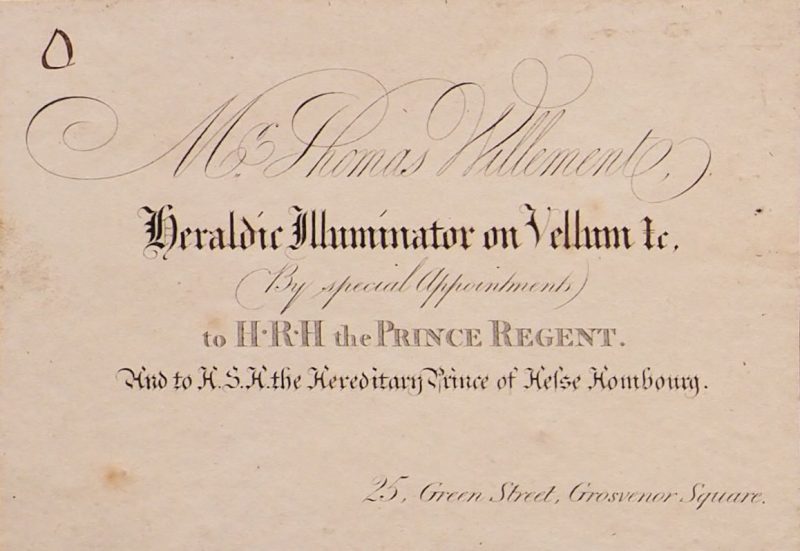

One of Thomas Willement’s early trade cards

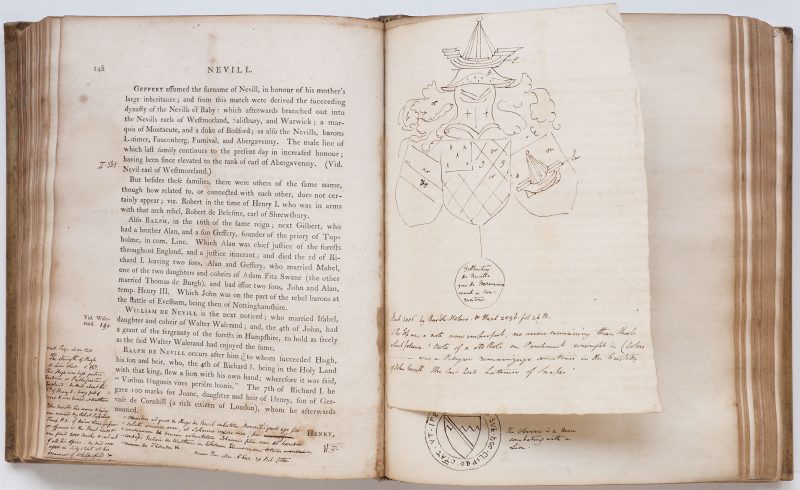

Born in 1786, he was the son of a London coach and house painter. In the days when coaches were emblazoned with the badge or arms of their owners, coach painters were often called upon to create heraldic designs. Young Thomas Willement seems to have made a speciality of heraldry and soon became somewhat obsessed with the origins of the countless historic emblems and designs which could (with the assent of the College of Arms) be added for an owner willing to pay. A diligent researcher, Willement filled many notebooks with the fruits of his enquiries, building the vast repertoire of medieval and gothic ornament he called on for his later designs.

A page from one of Willement’s notebooks

He acquired royal patronage and was not shy to advertise it. His trade card advertised ‘Heraldic Illuminator on Vellum &c, by special appointment to HRH the Prince Regent and to HSH the Hereditary Prince of Hesse Hombourg’. By 1840 he dubbed himself ‘Artist in stained glass to Queen Victoria’ and took on important royal commissions for St George’s Chapel, Windsor and for an armorial window for the great hall at Hampton Court.

Along the way he worked with designers who are now better known than he, notably AWN Pugin, who also settled in Kent, building the extraordinary edifice of St Augustine’s in Ramsgate. There was evidently some rivalry between the two men, and one wonders if Willement’s purchase of Davington Priory was a matter of keeping up with the Pugins in the Gothic Revivalist stakes.

Davington Priory from Willement’s Historical Sketch of the Parish of Davington, 1862

Whatever the case, Willement devoted 30 years to the loving restoration and adornment of the ruins he found at Davington. Originally a Benedictine convent with origins in the 12th century, Davington had been in a sorry state for a long time, even by the Reformation of the 1530s. Portions of it fell down over the following centuries, not helped by the 1781 explosion at the nearby Stonebridge gunpowder works which demolished outbuildings and two of the six original gables of the priory. Willement was left with the carcass of the original buildings to work with, allowing him to add fanciful ‘medievalist’ touches when it suited him.

East windows, Saint Mary Magdalene, Davington

It feels as though the buildings today are as much Willement’s creation as those of the original founders. He supplied the exquisite stained glass, depicting scenes from the life of Christ in faithful 13th century style, as well as a wooden pulpit cobbled together from pieces of various European churches and a fine font designed by John Thomas in 1847. Not evident today is most of the highly coloured wall painting he added to the interior of church in the belief (largely correct) that polychrome ornament recreated the original feel of the medieval church. Later generations seem to have disagreed, whitewashing the interior in familiar C of E livery some time in the 1930s, leaving only occasional shadows of Willement’s designs beneath. More of his wall painting survives in the priory accommodation, now the home of Sir Bob Geldof, and formerly of colourful antiques dealer and interior designer, Christopher Gibbs ― both owners who have cherished and preserved Willement’s intentions.

Thomas Willement died in 1871 and his work survives not just here in Faversham, but all over the British Isles, in country houses, churches (including the Inner Temple, London and the Round Church in Cambridge) and royal residences. His name is not widely familiar, even to specialists, and yet his work stands with the very best in the Victorian gothic revival.

With thanks to Carolyn Flanagan, Clerk to the Trustees of Faversham Municipal Charities and to the churchwardens of Saint Mary Magdalene, Davington.