Words Justin Croft Photographs Various, including British Library

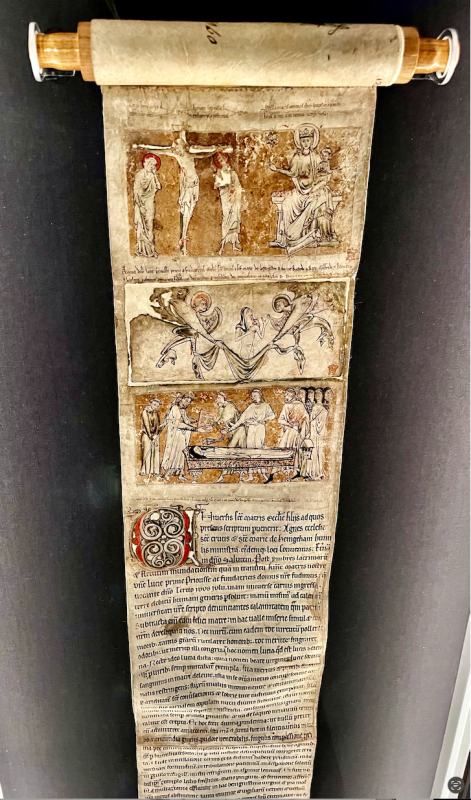

Part of the mortuary roll of Lucy of Hedingham British Library, Egerton MS 2849

The manuscript, known as the mortuary roll of Lucy of Hedingham, is one of the highlights of the brilliant Medieval Women: In Their Own Words exhibition at the British Library, open until March 2, 2025. I’ve visited four times now and am pretty sure I’ll go again before it closes. It’s one of the BL’s best shows in recent years.

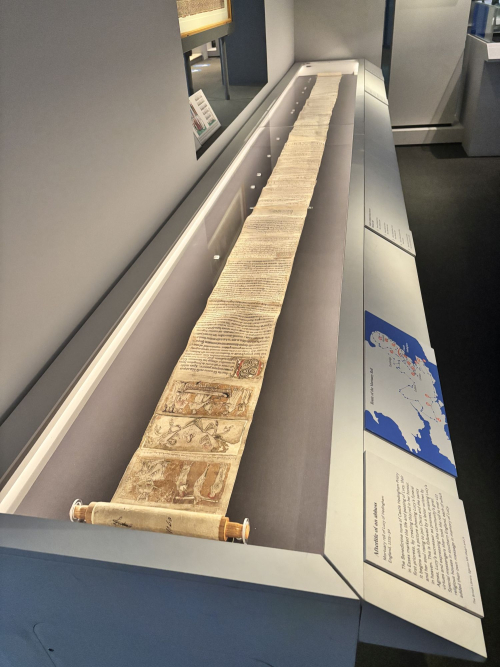

The top of the roll on display in the British Library’s Medieval Women exhibition

Lucy’s mortuary roll comes almost at the end of the exhibits and is unmissable, unfurled to more than six metres in its own specially constructed showcase. It consists of joined sheets of parchment with painted decoration at the top and a long roll of manuscript entries below. Scanning its length, and the helpful labels along the way, I was excited to see two familiar names picked out — ‘Faversham’ and ‘Davington’ and immediately wanted to know more.

The roll extended to its full extent

Lucy of Hedingham was prioress of an East Anglian nunnery at Castle Hedingham in Essex in the 13th century. When she died around the year 1225 this special document was made to celebrate her life and to record prayers for her soul. Most remarkably it was sent on a tour of southern England lasting several years, passing all the important religious houses. At every stop, the monks or nuns at each monastery or nunnery wrote a short entry on it marking Lucy’s passing and asking that her soul rest in peace. I suppose each inscription must have been accompanied by a service or some other subsequent ceremony that remembered Lucy in a list of prayers.

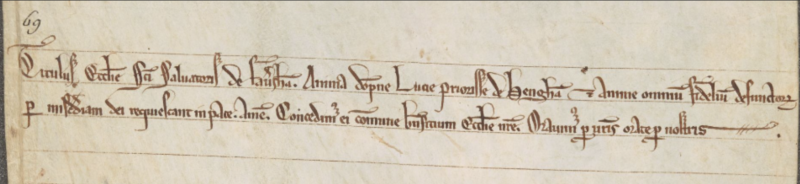

Faversham abbey’s inscription on Lucy’s roll

Over several years (roughly 1225-1230), the roll was carried by messengers around Southern England — through Essex and London, on to Kent, the south coast, parts of the West Country, the southern Midlands and back to East Anglia. The entries show us that the 122 stops on the itinerary included Rochester, Canterbury, Dover, Battle, Winchester, Glastonbury, Bath, Gloucester, Tewkesbury, Oxford and Ely. It’s striking to see Faversham and Davington in that company. Of course, Faversham Abbey’s status is well-known, but very little is known of Davington at this early date – its appearance on Lucy of Hedingham’s roll has hardly been noticed.

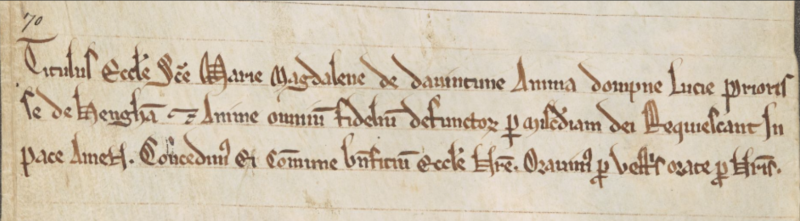

Davington priory’s inscription on Lucy’s roll.

I’m sure I have written this before, but I’m in awe of handwriting on documents like this made 800 years ago. As a left-hander, any fine writing seems miraculous to me, especially these days when most of us can barely sign our own name through lack of practice. These ancient scripts are truly superb, with their bold strokes — up, down and diagonal — showing mastery of the obliquely cut nib of a quill pen. Of course, the text is in Latin, and highly abbreviated at that, but it would have been entirely readable and remains so after eight centuries to those practised in palaeography.

I always want to know more about these scribes, and in the case of this particular document a special question arises. If, as with Davington Priory, many of the entries were made by houses of nuns not monks, should we assume they were written by women? Logic suggests yes, except that the orthodoxy of history tells us that at this date it was only men who wrote, usually monks at that. It’s extraordinary, but until recently very few have seriously considered the fact that women might also have been scribes, especially in the context of the nunneries. I’ve been excited to discover, therefore, that Lucy’s mortuary roll is actually the subject of a new academic project based at Stanford University in California, entitled Medieval Networks of Memory, which will map the journey of the roll and analyse its scripts, building up evidence for possible women’s writing in medieval England. Behind the project is Professor Elaine Treharne, a leading member of a generation of historians asking new questions of ancient sources and dragging medieval studies, well, out of the Middle Ages.

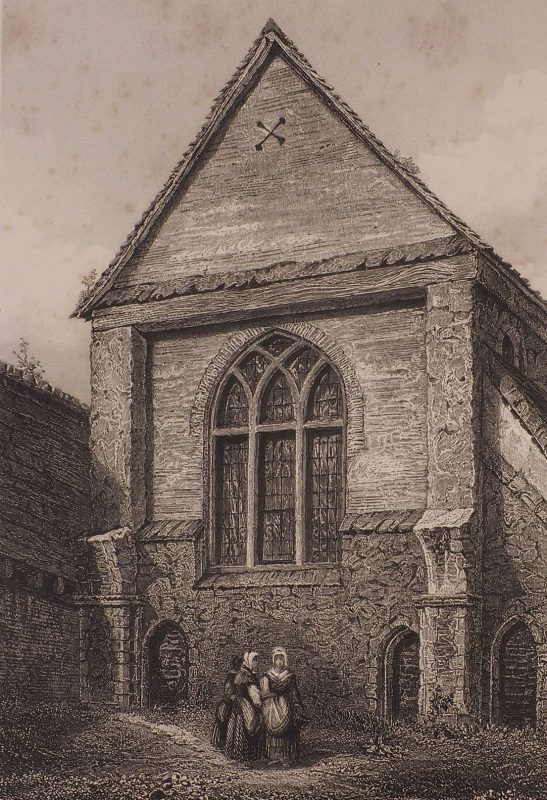

The ruins of Davington priory in the 19th century as seen by Thomas Willement

I contacted Professor Treharne, to ask about the writing on the mortuary roll and she came back with the following comment: ‘The person most likely to write these entries is the sacristan, or cantor/cantrix, officials in the nunneries and monasteries who were responsible for overseeing music for church services and the copying of manuscripts. Evidence in medieval texts shows that women were trained in these roles for their institutions, and there is no reason to doubt that women scribes were an integral part of their own religious institution’s holy work.’

Lucy of Hedingham’s soul been borne up to heaven

Besides the text of the roll, stretched several skins of parchment, the pictures at the top are breathtaking. There are three panels. One shows the crucifixion (the virgin and child on the right), another shows Lucy’s soul being borne aloft to heaven by two angels, and the third shows her body laid out on a bier with mourners around her. By any standards, these are masterpieces of English medieval art surely worth reconsidering. I see that a century ago, an antiquarian scholar attributed them confidently to ‘Master Walter of Colchester, or one of his brothers in art’. He may well be right, but like the handwriting of the document, surely that needs to be thought about again. Why shouldn’t a nun paint manuscript illuminations?

Lucy on her funeral bier, monks and nuns in the background

Professor Treharne is emphatic on these points: ‘Because women rarely sign their work, and because contemporary researchers must battle with the inherited misogynies and sexisms of past scholarship that elided women’s intellectual, social, and cultural contributions, medievalists have, until recently, been reluctant to highlight the identity and roles of women scribes. This is now a rapidly changing field of exploration, helped by amazing initiatives like the British Library’s exhibition.’

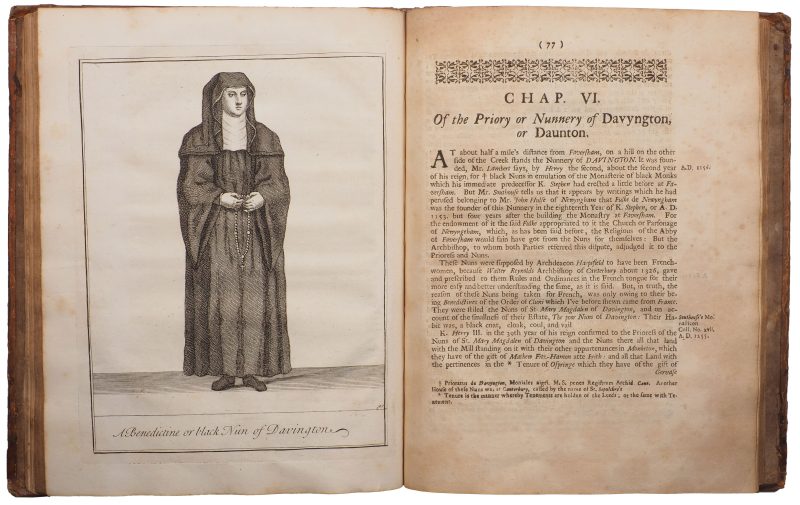

A Davington nun, imagined in the 18th century, from Lewis, ‘History and Antiquities of the Abbey and Church of Faversham in Kent’, 1727.

If you’re fortunate enough to get to the Medieval Women exhibition before it closes, and I’d urge you to try, you’ll see an entire exhibition showing us why, when we think about it, women were active in medieval society in ways that have been forgotten or obscured by generations of historians. You’ll see examples of writing, painting and other arts made by women all over Europe, but especially in England, and its surely worth the pilgrimage to see the names of Faversham and Davington on a document written eight centuries ago.

With special thanks to Professor Elaine Treharne, Stanford University.

For an excellent introduction to Lucy of Hedingham’s roll, do read the BL’s own blog post by curator Calum Cockburn

For more information on the exhibition, click here.