Words Posy Gentles Photographs Various

The silenced spring at Harty Ferry, Oare

There is a strange silence at Harty Ferry. Since the end of last year, the steady sound of water pouring from the spring, which was the sound of arriving at Harty Ferry, has stopped.

It has been oddly disturbing. Faversham News dredged up a (rather spurious?) local saying: ‘When the spring at Harty runs dry, the riders of the apocalypse are nigh.’ Someone suggested on facebook that the council had ‘stolen’ the water, others that conservation works in the area had caused a leak. The Harty Ferry spring has long been a source of Faversham apocrypha. Some say that the water comes from the Alps and that someone once poured dye into the water in the Alps and it came out of the well at Harty Ferry. How patient the man who sat and waited.

The spring is found by the Oare Marshes Kent Wildlife Trust reserve – an important wetland reserve fluttering and twittering with overwintering birds and spring migrant birds. The problem with the spring is a loss to the parched walkers, birdwatchers and sailors who frequent the marsh, and a deprivation of one of the pleasures of Faversham life. Fern Alder, who arrived in Faversham a few years ago and is a founder member of Friends of the Westbrook, says: ‘I can’t tell you how much I’m missing it. It was the highlight of my time here and a really valuable resource. I drank it and cooked with it. I do what I can now with filtering tap water – but it’s not the same.’

The water is tested annually for purity by the environmental health team at Swale Borough Council. Janet Hill, Climate Change Officer, says: ‘It has never failed a test for public health.’

We took it for granted. The spring seemed god given, pouring steadily and unchangingly, its temperature constant so that in winter it almost had warmth. And there was a pleasure in that it was entirely uncommercial. One could fill one’s bottles with water that tasted sweeter and purer than any among the ranks of mineral waters on the supermarket shelf and did not fill the world’s seas and shores with tides of plastic bottles.

In a quest to discover how this jewel can be restored to Faversham life, Faversham Life found that the loss of the spring water is not a problem of the apocalypse but of plumbing – the pipe is broken – and that Kent Wildlife Trust is responsible for fixing it. We spoke to Stephen Weeks, Estates Manager of the Trust, who said: ‘As I understand it, as the well is a private water supply on the Trust’s land we are responsible for it. While we certainly wish the well to be in action again, I can’t give a definitive answer until I have a clear idea how much the repair work will cost.’

Mr Weeks told us: ‘As you have noticed, the well water is now flowing out at ground level and no longer reaches the spigot. We believe this is due to the main cast iron stand pipe becoming corroded, due to its age, at or below ground level. Repairing the well would involve inserting a new stainless steel liner into the stand pipe and sealing around the bottom, to ensure water passes up the new pipe rather than flowing around it. This work requires a specialist water engineering company and to date we have had difficulty finding somebody that is interested in giving us a quote. We are continuing to look and have received help from South East Water but we currently have no idea of the potential cost or timescale.’

We asked about the history of the well and Mr Weeks told us that the existing eight-inch well was bored by Mr R D Batchelor in 1900 for the Mining Machinery and Improvement Company and goes down to a depth of 76m (250 feet). ‘The current brick structure was built in the mid-1990s when Kent Wildlife Trust carried out repairs to the damaged stand pipe and put a concrete cap over the potentially dangerous well head.’

Harty Ferry

Faversham Life then asked Mark Carpenter of the specialist company, Borehole-driller, what could be done to restore the spring. We quote his reply in full in the hope that it will help.

Mr Carpenter said: ‘I’ve taken a look at the well record and it appears that the depth to the chalk is 55 metres and the depth of the well is just over 75 metres below ground level. I have seen photos showing the water flowing from a spigot off the well casing, but from speaking to you it appears that this no longer flows and the water comes out of the casing just below ground level.

‘The cost of installing stainless steel casing would be very expensive, but using Water Regulations Advisory Scheme approved pvc casing would be a lot cheaper and is the preferred choice for modern wells. I would suggest installing a new pvc liner into the existing water well, the diameter of the new casing would be 112mm or 145mm. The new liner would consist of plain casing to a depth of 55 metres and then slotted casing from 55 to 75 metres. The slotted casing is machined to optimise the flow of water into the borehole. The slotted section would then be surrounded by a gravel filter, this allows the water to travel freely through the slotted casing. From 55 metres to ground level we would backfill with bentonite pellets – bentonite is an inert clay. The pellets are coated to allow them to sink to the bottom and after about 20 minutes, they start to expand and then form a permanent seal. The seal will then stop the water from coming up between the well casing and the new liner. It will also stop the area flooding.

‘The reason that the water is artesian is because the natural water level in the chalk is above ground level, it is therefore known as a confined aquifer. The easiest way to stop the flow is to increase the height of the pipe until it gets to its natural level, I don’t think it would need to be raised very much (probably a metre or so).

‘To finish the well off I would suggest extending the existing well casing with perhaps stainless steel casing to provide protection against vandalism as the pvc casing would be relatively easy to break. Finally you would need to decide how you would like to control the flow of water. Perhaps fit a couple of taps onto the stainless steel pipe. I think you would need to find out from the people who actually use it, they would tell you whether taps were the right decision, or perhaps you still just want a continuous flow from a spigot.

‘There are too many variables to give an accurate quote, such as access, final specification, unforeseen circumstances etc, but the main cost in a water well is the actual borehole and you already have that. I would say to fit the new liner and fabricate a new well head would cost no more than £10,000, and may be a lot less if the installation goes well.’

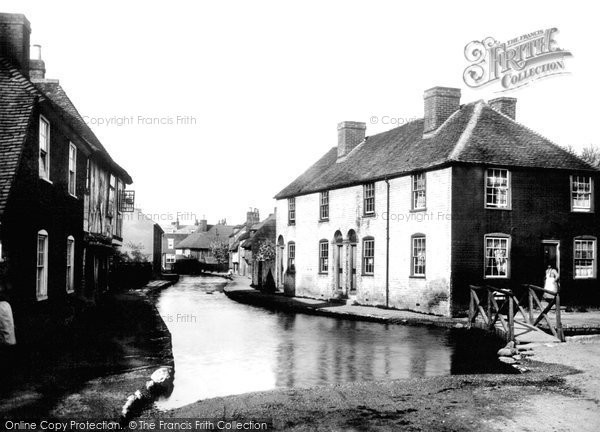

The spring when it was in full flow

This certainly gives us all something to think about. Fresh water as well as salt has been the making of Faversham, and in particular the purity of the water in the aquifers that run beneath the town. Shepherd Neame is the present thriving sign of the importance of water to Faversham’s industry. It is built above its own artesian well, using the same chalk-filtered mineral water that pours out at Harty Ferry, to create its famous beers. They say: ‘All the water we use in brewing comes from an artesian well deep beneath the brewery. The water is filtered by Kentish chalk – a very long and slow process – and by the time we extract it we have a natural mineral water on our hands. Due to the chemical make-up of heavily treated tap water, natural water is also preferable to use in brewing because of the consistency it offers.’

Faversham has been making beer since 1147 when the Cluniac monks at the Benedictine Abbey founded by King Stephen began making ale with locally grown malting barley and the town’s pure spring water. In the past, Faversham’s water was more visible. Water Lane in Ospringe was a nailbourne with bridges to cross it. But as the 20th century advanced, more and more of this water was diverted into culverts and sent underground and it would be a tragedy if the boggy seeping which has currently replaced the exuberant outpouring of this water at Harty Ferry becomes the norm.

Water Lane in Ospringe in 1892

There is an excellent paper by the Faversham Society Archaeological Research Group on the St Ann’s area of Faversham which explores the importance of water to the town’s development. Until about 1550, there were medieval watermills along the Westbrook. They were succeeded by the manufacturing of gunpowder at the Home Works, of which Chart Mills is still a visible sign. Gunpowder manufacture continued until the 1930s when watercress beds were planted in the old millponds. Watercress requires pure water which is mineral rich, so the water of Faversham was ideal and the business thrived until the late 1960s, when the millponds were filled in, the Westbrook culverted and the 400 houses we see today were built on the St Ann’s estate. There’s still a lot of watercress around – in the stream by the Stonebridge allotments and at the spring in Harty Ferry.

The Westbrook stream which runs into Stonebridge pond has been the source of industry and life in Faversham for centuries, yet until the marvellous clearing work of Friends of the Westbrook, it had become little more than a ditch, culverted in the late 1960s upstream in Ospringe, and spiked with rusting supermarket trolleys and plastic shopping bags dragging and tangled in the weeds. Its history is marked by the road names on the St Ann’s estate by which it runs – Chart Close, Cress Way, Millstream Close. Nobel Court is named after Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite and the man behind the Nobel Prize.

Faversham’s pure water is still a valuable resource and one that we can all share in.

Text: Posy Gentles, Photographs: various