The splendid 19th century almshouses in South Road are redolent of the very best of high- minded Victorian philanthropy. They look as if they have been transplanted from an Oxford college, or a muscular 19th century public school. The largest almshouses in Kent, the main range extends some 143 metres, punctuated in the middle by a commodious chapel.

The Almshouses designed by Hooker and Wheeler after a competition in 1862-3

At the beginning of the 19th century, a handful of almshouses were scattered around the town. In the 1850s a plan to accommodate all the almshouses on one site was first mooted, following a substantial legacy to the town of some £80,000 by Henry Wreight, a solicitor and three times mayor, and fortunately for Faversham a bachelor. Wreight’s house survives in the Mall. His bequest also paid for the Recreation Ground. Remarkably his legacy still aids Faversham Municipal Charities, established when a national reform, the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, transferred administration of the town’s charitable funds from the corporation to a new body of charity trustees.

The Trustees’ instructions to architects competing for the contract to design the 30 new almshouses included strict criteria: each dwelling was to have a sitting room, a kitchen, two bedrooms, the ‘necessary outbuildings and as many as possible of the houses must communicate with the Chapel by a covered way’. The Trustees decided that ‘an eminent architect’ should be employed to look at the designs and estimates. At the time George Gilbert Scott, architect of the Albert Memorial, was working on the tower and spire of St Mary of Charity, but he declined due to pressure of work. The task fell to Benjamin Ferrey, a Gothic Revival architect who restored and designed scores of churches all over Britain.

Detail of fine Victorian door furniture

Hooker & Wheeler of Brenchley, Kent, won the building commission. They recommended the houses should be built in red brick with Bath stone dressings as they felt Kentish rag would be ‘too cold in appearance’. How right they were. The red brick has warmth and the façade is skilfully articulated with projecting bays and gables creating a pleasing rhythm.

Arcading with rich foliage caps and moulded arches

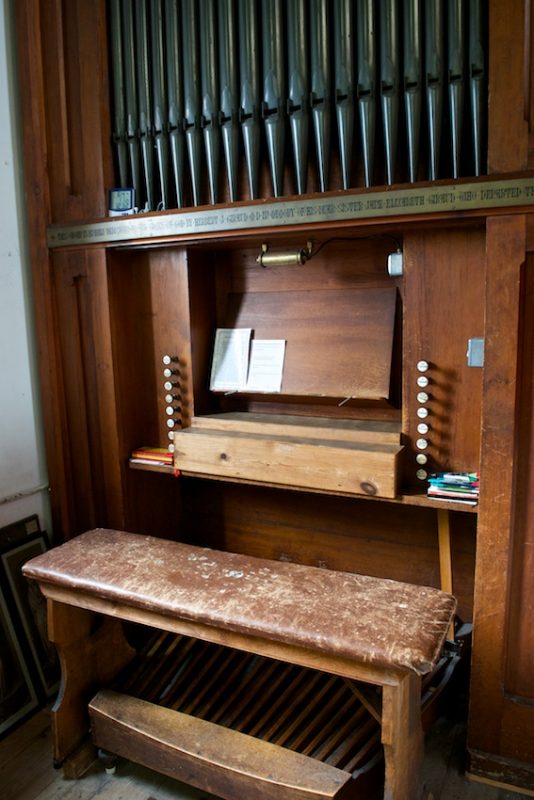

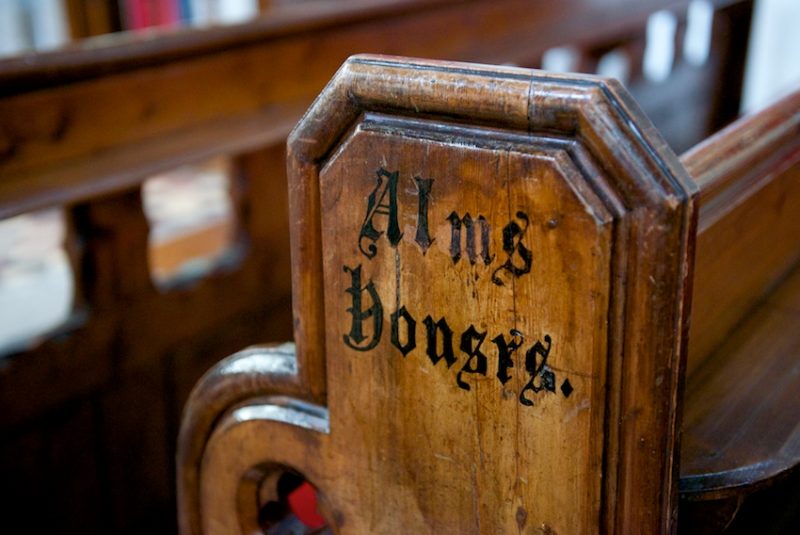

The Chapel was to be built entirely in Bath stone so that ‘it would stand out but harmonise with the dressings on the dwellings’ and the internal dressings of the Chapel were to be of Caen stone. The interior has much to delight including an organ by Henry Willis & Son, sometimes known as ‘Father Willis’, the leading Victorian organ builders. St Paul’s, Canterbury and several other cathedrals boast a Willis organ. The pews each bear the hand-painted inscription, in spiky gothic script, ‘Alms Houses’.

‘The interior of the chapel is really convincing,’ writes John Newman in the Pevsner for Kent: North East and East

The organ built by Henry Willis & Son, sometimes known as ‘Father Willis’

A pew end

There are fine Minton encaustic tiles and excellent examples of early and late Victorian stained glass: the West Window was designed in 1844 by Thomas Willement, a leading figure in the revival of stained glass in the 19th century who lived at Davington Priory. It was originally the east window of St Mary of Charity, but was moved in 1911. The window in the apse was designed by Lavers & Westlake in 1895. The chapel is open every day, and services are held regularly.

In 1982 the Queen Mother, as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (Faversham is a member of the Confederation of the Cinque Ports), re-opened the flats following a £1 million renovation, and in 1989 an additional 16 flats were built on the rear of the site, very much in the spirit of the original design using local red brick, stone corbels and clay peg tiles. There are 70 flats in total. Applicants for accommodation must have lived in the town for at least five years.

Henry Wreight would no doubt be thrilled to see that his legacy is still benefitting the town well into the 21st century.

Text: Amicia. Photographs: Lisa