Words Posy Gentles Photographs Posy Gentles, Amicia de Moubray, David Thomas, Paul Weller

Sheerness: A military history

In late October, Faversham Life set off to follow, more or less, The Sheerness and Bluetown Heritage Walk on the Isle of Sheppey, which has just been published. We discovered how much we didn’t know about Faversham’s neighbour across the Swale.

We began our walk at the yellow brick and sandstone, neoclassical Dockyard Church which, now restored (see the story here), stands at the entrance to the Sheerness dockyard. The Church is an imposing reminder that, for 300 years, this was one of the most important, ambitiously built, and militarily strategic Royal Navy dockyards in the country until it closed in 1960 when the Admiralty sold it and it became a commercial port. Despite 20th century demolition, several of the fine late Georgian buildings from the Dockyard’s splendid rebuilding in 1815-1830, have been preserved. To the south of the Church we admired the handsome Grade II* Naval Terrace which Pevsner described as looking ‘like a piece of Woburn Square’.

A town for Dockyard workers, Sheerness didn’t have a church until 1828

The Naval Terrace

In the 16th century, Henry VIII realised the strategic importance of the peninsula at the northwestern tip of Sheppey, situated where the Medway runs into the Thames Estuary, and built a lonely garrison to defend the Medway from invading enemy ships.

But Sheerness remained mostly uninhabited ague-ridden marsh until a century or so later when, in 1665 Samuel Pepys, Clerk of the Acts for the Navy Board, authorised work to begin on a dockyard at Sheerness. The town at Sheerness grew from the dockyard. Pepys wrote in his diary: ‘To Sheerness, where we walked up and down, laying out the ground to be taken in for a yard, to lay provision for cleaning and repairing ships, and a most proper place it is for the purpose.’ Building started on 27 April but not two months later, the site was captured by the Dutch who destroyed the fort at Sheerness, then used it as a base to sail up the Medway, breaking the defensive chain, setting fire to several ships including the Royal James, and making off with the Royal Charles. Humiliation indeed – Charles II had returned from exile and regained the throne only five years previously. If there had been any doubt, this catastrophe emphasised the military necessity for a dockyard at Sheerness.

Aerial photograph showing the Sheerness peninsula and the Queenborough Lines. Photograph by Paul Weller for the Missing Pieces project of Historic England

The Sheerness peninsula is roughly triangular with the Dockyard at its northwestern tip. The west-facing coast looks across the Medway to the Isle of Grain. However, from the Church, we crossed the bridge and walked north to the coast where the Thames Estuary spills into the North Sea. From there, we could clearly see the coastline and tower blocks of Southend-on-Sea to the north west, and to the east in the North Sea, the desolate World War II Maunsell sea forts, Red Sands and Shivering Sands. Beyond that unseen, lie The Netherlands.

The view across to Southend-on-Sea

We continued our walk along the sea wall and, using binoculars, were able to see clearly the ragged masts of the wreck of the SS Richard Montgomery, sticking out of the sea. The ship ran aground in 1944 a mile off the coast of Sheerness carrying 1400 tonnes of explosives destined for the Allied war effort. The explosives are still on board and there is an 80 metre exclusion zone which can only be crossed by permission of the UK Home Office. It is continuously monitored by radar surveillance and surrounded by buoys.

Myths abound. Some say the explosives will have lost combustibility by now; others that we are in constant danger of an explosion which would cause a tsunami so vast that it would drown Sheppey, Sittingbourne and Faversham. We found a sinister, uncredited poem painted on the steps leading down to the pebbled beach. Although worn away in places, we could make out the words: ‘The truth of it, this wartime souvenir, is common knowledge. But whisper to yourself, that you can see the end of the world from here.’

An uncredited poem is painted on the steps of the sea wall looking out to the wrecked masts of the SS Richard Montgomery

The sea wall is high, and on the land side only the three-storey houses on Marine Parade have a sea view. Here lived the famous German writer Uwe Johnson, battling writer’s block and alcoholism, from 1974 until he died a decade later. In 2020, the cultural historian Patrick Wright wrote The Sea View Has Me Again about Johnson’s time in Sheerness and his writing about the people and the town.

The sea wall at Sheerness

The charming Neptune Terrace faces inland from the sea wall

Neptune Terrace detail

Neptune Terrace detail

Neptune Terrace detail

The grander houses of Marine Town are to be found along the sea wall

The Ship on Shore with attached grotto. There is a story that a ship full of barrels was wrecked here. The locals believing the barrels to be full of whisky rushed out to retrieve them. Finding them instead to be full of hardened cement, they used them to build this pub and grotto

The area below the sea wall here is called Marine Town. The town of Sheerness is made up of Blue Town, Mile Town and Marine Town. Unlike the rest of Sheppey which is largely rural, Sheerness is entirely built up, although Minster is the most populous town on Sheppey. As there was no settlement near the dockyard, the Navy took the unusual step of providing habitation to attract workers. Initially, accommodation was provided in hulks and barrack-like lodgings in the dockyard housing around 1000 people by 1774. In the mid 18th century, dockyard workers started to build their own houses just outside the dockyard with materials they were allowed to take from the yard. These houses were clinker-built out of wood like ships and the blue naval paint used to paint them led to the area being called Blue Town. Mile Town (a mile from the docks) followed later in the 18th century, followed by Marine Town in the mid 19th century. Most Sheerness residents worked at the dockyard.

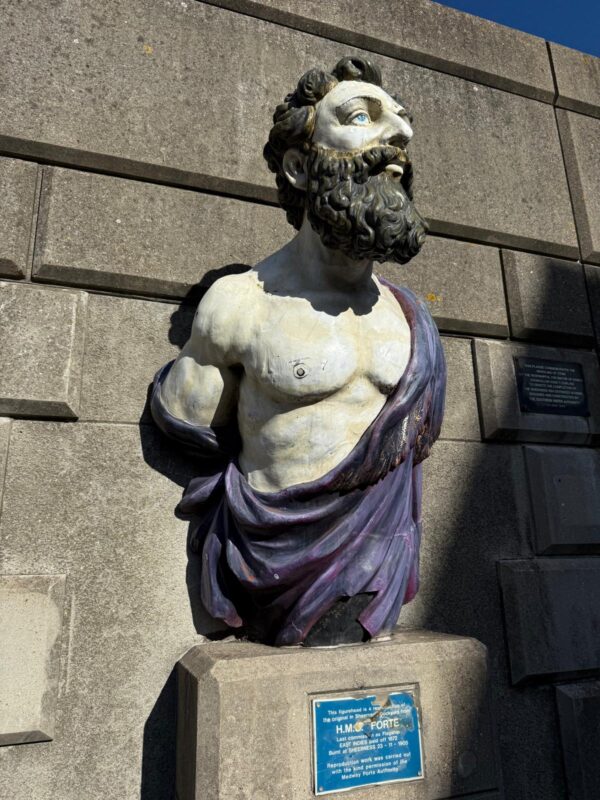

A reproduction of the figurehead of HMS Forte. The original is in the Dockyard

At the reproduction of the HMS Forte figurehead on Marine Parade, we took a detour from The Sheerness and Bluetown Heritage Walk because we wanted to see the Queensborough Lines which bring Sheerness to an abrupt stop, slicing the peninsula from the rest of the island in a remarkably straight line.

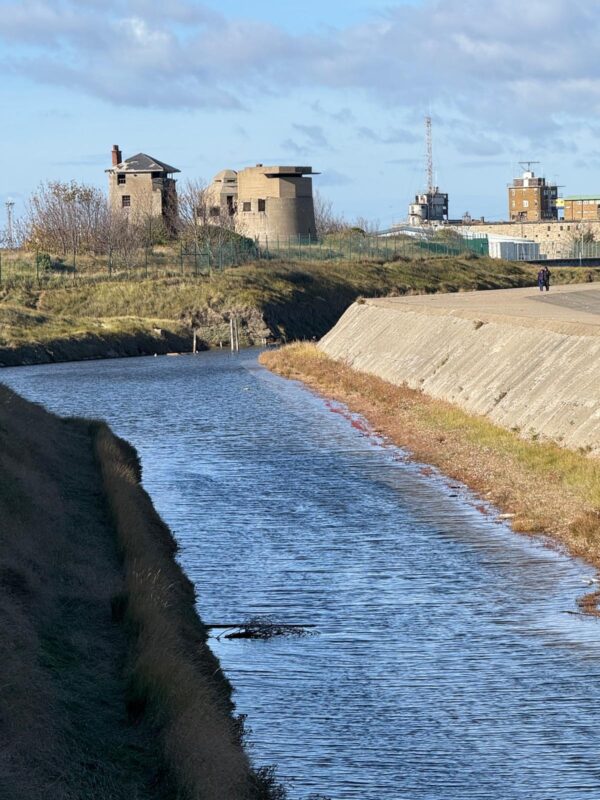

The Queenborough Lines are a defensive arrangement of ramparts and a waterway. The canal, which acted as a moat to defend the dockyard from attack on the landward side, was dug in 1782. In the 1860s, the Lines were reinforced in reaction to the fear of renewed French expansionism under Napoleon III and the Second French Empire. During World War II, additional defences and air raid shelters were added. The Lines run straight across the marshes for just over two miles from the south west at Queenborough on the Medway coast, to the north east Thames coast at Barton’s Point. Today, there is a leisure park at Barton’s Point and the water for a boating lake is fed by the waterway.

We looked across the water, with the grids of terraced houses behind us, and saw only marshes and the hill of Minster gently rising in the distance. It is notable about Sheerness that the main communication routes connect with the mainland rather than the rest of the island.

As we walked along the canal, we met dog walkers and saw a game of football, and the odd construction that spoke of a military past.

The Queensborough Lines

Remnants of a military past

Turning off from the Lines, we made our way back through the alleys of the Victorian terraces of Marine Town to meet up with the Heritage Walk again and the town centre. We passed Sheppey Little Theatre which opened in a late 19th century church hall in 1975, marvelled at the elaborate, green-painted Sheerness Clock Tower, and even more at a black Lamborghini, growling throatily as it idled at the side of the road, attracting bystanders like flies.

The grid arrangement of 19th century terraced houses with wide back alleys

Sheppey Little Theatre

The Sheerness Clock Tower: the largest freestanding cast-iron clock tower in Kent. 36 feet tall and built in 1902 at a cost of £350 to commemorate the coronation of Edward VII

An old travel agency in the town centre

A maritime history marked at the Belle and Lion pub

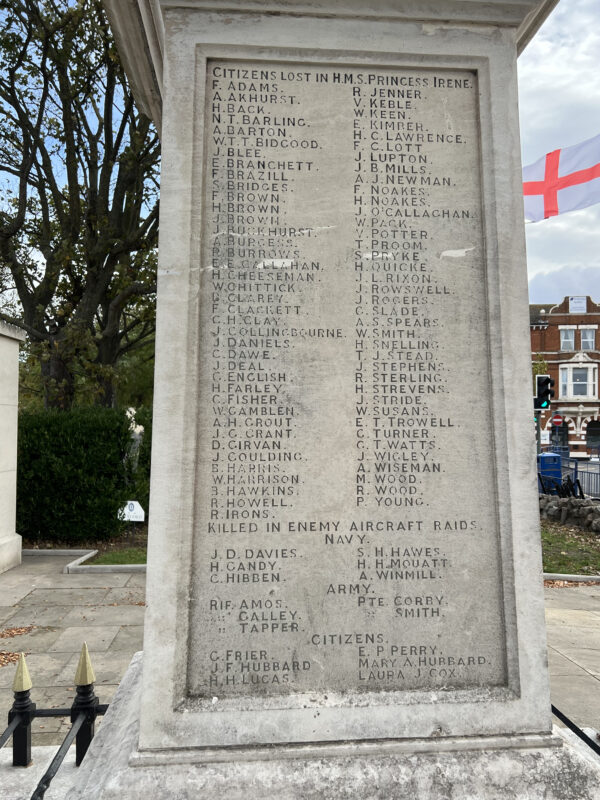

Our last stop was the Sheerness War Memorial – the figure of Liberty aloft among flying flags. As tragic as those names who lost their life fighting, were those who lost their life through accident. We read of the victims of HMS Bulwark which exploded while based at Sheerness in 1914, killing 788 men. Among those killed were six 15-year-old sailors: Midshipman William Ellice, Signal Boy Benjamin Spencer, Midshipman Evelyn Williamson, Royal Marines Bugler Philip Bullen, Boy 1st Class William Kellow and Midshipman Charles Wilson. In 1915, the HMS Princess Irene exploded while moored off Sheerness, with a loss of 350 people, including a farmhand and a nine-year-old girl who were hit by flying debris half a mile away.

Sheerness War Memorial

The names of citizens lost in the HMS Princess Irene

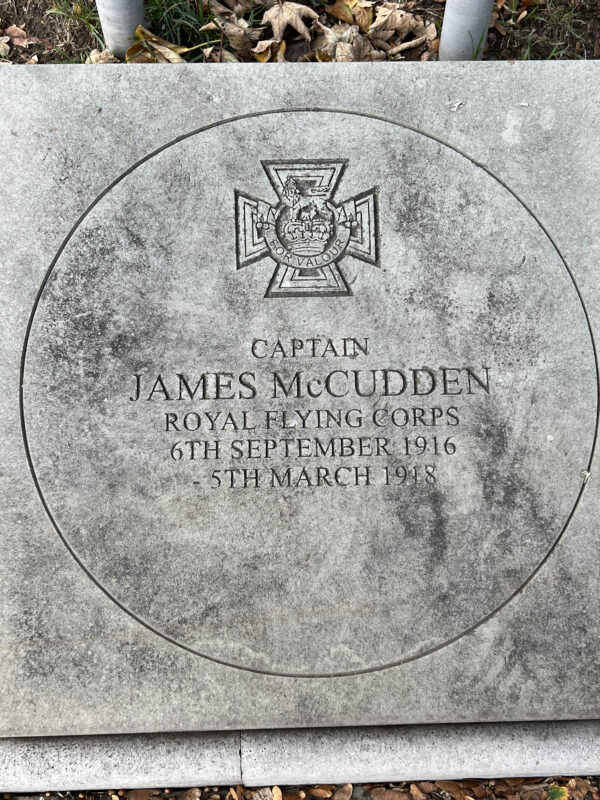

Capt James McCudden who was awarded the Victoria Cross

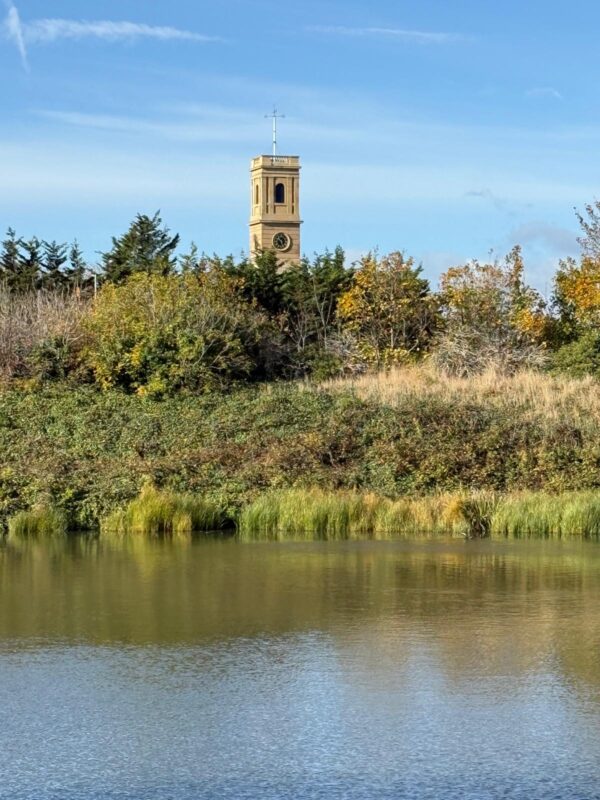

We made our way back across the bridge, watching the boys fishing from the bank, towards the tower of the Dockyard Church, its yellow sandstone echoing the falling autumn leaves.

The Dockyard Church Tower

Some things you may not know about Sheppey

* Sheerness beach has been awarded a 2025 international Blue Flag and the Seaside Award and has three stars for excellent water quality.

* The rebuilding of the Royal Dockyard at Sheerness between 1811 and 1829 produced one of the wonders of the early industrial age. Its engineer was the great John Rennie, whose plan (which included state of the art dry docks) involved the sinking of millions of timber foundation-piles into the marshy land. The yard was constructed in a single campaign between 1811 and 1830 under the supervision of successive naval architects Edmund Holl and George Ledwell Taylor. Despite extensive demolitions during the late 20th century, many of its buildings survive, all built to the highest standards and characterised by strong, simple Greek-revival detailing. (An excerpt from the FL article written by Will Palin Read here)

* In 1909, the Short brothers set up the world’s first aircraft-building factory in Sheppey. With a licence from the Wright brothers, they built six Wright ‘Flyers’, and their own ‘Short No 2’ aeroplane.

* The last case of home-grown malaria was recorded on the Isle of Sheppey in 1952. There are about 10 species of mosquito found on the North Kent marshes – the predominant species being Anopheles atroparvus. Gabriella Gibson, professor of medical entomology at the University of Greenwich, explains why we now have nothing to fear: ‘Anopheles atroparvus was responsible for transmitting a species of malaria that has not been seen for decades in Europe and is assumed to be extinct (or more accurately, not found in mosquitoes or humans for decades, and therefore unlikely to still be present). Malaria was certainly present in the UK and is no longer and the reasons are mainly changes in social conditions over the decades.’ (Taken from the FL article Maligned Marshland)

* Thomas Cheney (or Cheyne) 1485-1558, one of the few who kept his head, riches and influence during the reigns of five Tudor monarchs, inherited Shurland Court on Sheppey and is buried in St Katherine’s Chapel at Minster Abbey.

* The Faversham Society Paper No 64 Beowulf in Kent, written by Paul Wilkinson and Griselda Mussett proposes that the heroic poem Beowulf was actually set on the Island of Sheppey.

* The novel Wide Open, winner of the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, is set in Sheppey and is highly evocative of this distinctive island. It was written by Nicola Barker who presently lives in Faversham. Her latest novel is Tony Interruptor published in August 2025.

Text: Posy Gentles. Photographs: Posy Gentles, Amicia de Moubray, David Thomas, Paul Weller

You can download The Sheerness and Bluetown Heritage Walk here

Swale’s proposals for conservation areas in Sheerness can be read here