Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft and others

Feeding on light – November 2021

French philosopher Simone Weil once wrote about ‘feeding on light’ as a way of counteracting darkness. She meant it in a spiritual and philosophical sense but as the nights draw in it’s an idea to take literally — making the most of daylight hours and devouring sunlight where we can in anticipation of winter. Coming across this appealing metaphor reminded Faversham Life of Simone Weil’s surprising if tragic local connection.

Simone Weil Avenue, Ashford

As you drive into Ashford from Faversham you might notice the road sign for Simone Weil Avenue off to the right, marking a nondescript stretch of dual carriageway skirting the town centre. It’s unlikely you will have given it a second thought, still less stopped to look at the other sign beside it which explains that Weil died in an Ashford sanatorium in August 1943 and is buried in Bybrook cemetery. We can hardly claim her as a local, but her road sign memorial is a small tribute to an extraordinary life.

The philosopher’s grave, Bybrook cemetery, Ashford

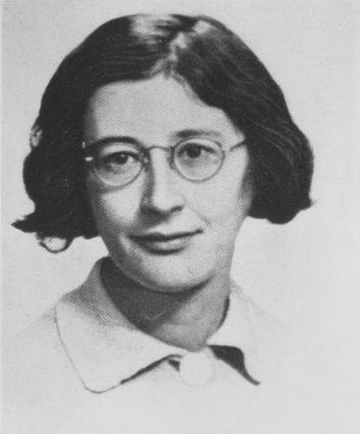

Simone Weil was born in Paris in 1909, daughter of non-practising Jewish parents, and showed precocious intellectual talents. She learned Greek and Sanskrit at a young age in order to read the myths and the Bhagavad Gita in their original languages. She later became one of the first women to enter the elite École normale supérieure in Paris in 1927 (Simone de Beauvoir was a fellow student). She was quickly drawn to political activism, joining various Marxist-inspired trade-union causes and it was here too she developed her profound sense of altruism and social justice. Though a professed pacifist she travelled to Spain to join the anti-Fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War, and at the outbreak of the Second World War she remained in France with her parents in the unoccupied zones of the South before leaving with them for the United States in 1942. As a Jewish family, regardless of their agnosticism, their situation was perilous. She soon returned to Europe, staying in London where she worked with Charles de Gaulle’s Free French movement, and at the time of her final illness and death she had just been recruited to the Special Operations Executive (SOE) with a view to entering France as a secret radio operator. She was admitted to Middlesex Hospital with pulmonary tuberculosis in April 1943 but was soon transferred to the Grosvenor Sanatorium in Ashford. Her death there at the age of 34 was from tuberculosis, but her death certificate recorded a verdict of suicide while of disturbed mind. Throughout her life, Simon Weil developed a self-destructive habit of abstaining from food in solidarity with those less fortunate than herself. Even as a child she refused sugar on the grounds that it wasn’t available to soldiers fighting in the Great War while as a young woman she would eat only what was strictly necessary. It was reported that in her last months she had stopped eating in recognition of the privations of her kinfolk suffering in Europe, a fact which surely brought on her final illness, if not her actual death.

Simone Weil (public domain image)

The bare bones of her biography tell us little about her thought and writing which are her most enduring legacy. Throughout her short life she wrote prodigiously, not often with a view to publication, but she filled many notebooks with her philosophical and spiritual thinking. Most of this was not published until after her death and it is therefore doubly remarkable that she is now hailed as one of the towering figures of European philosophy in the 20th century. She has influenced a host of literary and religious figures, from T S Eliot to Iris Murdoch and Pope Paul VI to Rowan Williams. Eliot wrote of her, for example: ‘We must simply expose ourselves to the personality of a woman of genius, or a kind of genius akin to that of the saints’.

Weil’s philosophy was uncompromising and not often one of consolation. She wrote of the world as subject to laws of physical and spiritual gravity, weighing heavily on humanity, alleviated only by occasional flashes of divine light grace. Recognising that she wrote under clouds of violence, genocide and war in the 1930s and 40s, it’s not hard for us to see why. Reading her now, we search in vain for that sense of ‘all shall be well’ offered by the medieval mystic Julian of Norwich. For Weil, God was an absence — not a constant presence — one whose existence could only be detected in passing. For her, human acts of compassion, kindness and friendship might be signs of God, just as recognising light and beauty in art, poetry or music can be a conduit to the divine.

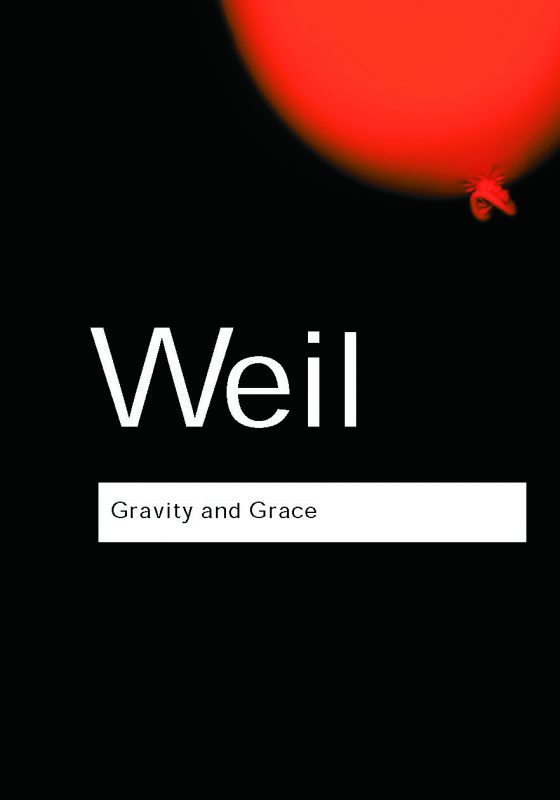

A good introduction to her thought is Gravity and Grace. A small book, it comprises selections from her notebooks entrusted to a friend before she left for America and was only published after her death. It’s the sort of book to keep close at hand and not one that needs to be read from cover to cover — a sentence chosen at random is often enough to provoke reflection and inspiration. It first appeared in English in 1952 but is easily available in paperback. It is here that Simone Weil wrote of the need for humans to feed on light by cultivating a kind of spiritual chlorophyll. In common with many other spiritual beliefs around the world her philosophy hinges on the need to negate the self and to do away with the ego. She saw herself as a Christian but she had little time for organised religion and it’s likely she was baptised only in the last few days of her life.

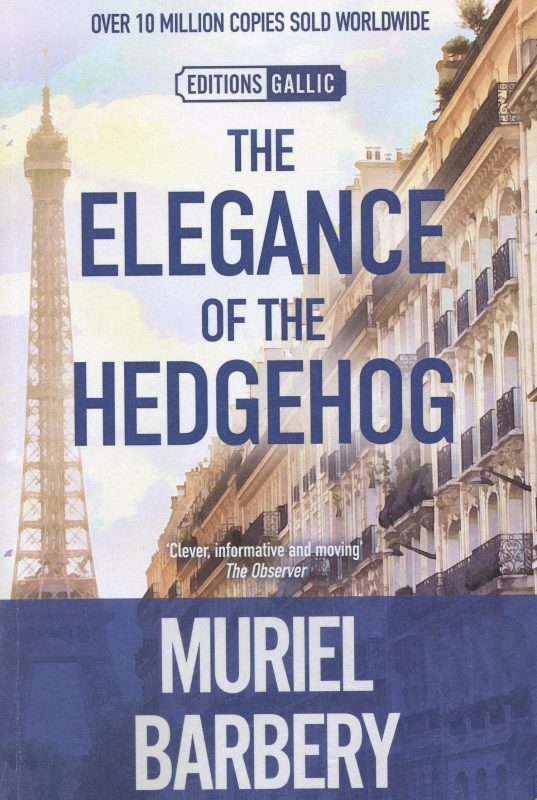

Another way into Simone Weil’s philosophy is the recent novel by French author Muriel Barbery, The Elegance of the Hedgehog, which has proved a book club favourite and was serialised on Radio 4. Barbery sets Weil’s concepts of gravity and grace in motion among the inhabitants of a Parisian apartment block with enjoyable and illuminating results and it’s a life-affirming book which successfully applies the quality of grace to all sorts of everyday situations — a game of rugby on TV, conversations between strangers, random acts of kindness, tea and cake with friends, bonsai trees, chance encounters and even charity towards a neighbour’s cat. Typically and stylishly French, it brings colour and optimism to Weil’s austere thinking and tragic personal history. Offering a multitude of ways in which we can cultivate the habit of feeding on light, Barbery’s novel is warmly recommended as an antidote to long winter nights ahead.