The Allan Beckett memorial window

What is the connection between a mulberry tree in a garden in Abbey Street, the artificial harbours built by the Allies on the coast of Normandy in 1944 and a stained glass window in St Peter’s Church Oare? The answer is Allan Harry Beckett MBE. He was the civil engineer who designed the floating roadways and anchor systems for the temporary harbours that made it possible to land troops and equipment on the Normandy beaches in June 1944. ‘Without Allan’s designs, Mulberry Harbour wouldn’t have worked, and without Mulberry Harbour there would have been no liberation of Europe.’

This is the informed view of Allan’s son Tim, Director of Beckett Rankine, the marine civil engineering consultancy. Allan is the protagonist of the story, and provides the connections, but there is coincidence also in the recurrence of mulberries. The first is the venerable mulberry tree planted in the garden of 83 Abbey Street, probably in the 17th century. Allan and his wife Ida bought the house in the late 1980s. It still belongs to the Beckett family and is currently occupied by Tim’s brother, Dr Michael Beckett.

The mulberry tree seen from the Abbey Physic Community Garden

Some of the branches of this tree hang over the wall into the Abbey Physic Community Garden, and when they are laden with dark, luscious fruit, volunteers make delicious jam, which sells out instantly and boosts charitable funds. This was where I first learnt of the Allan Beckett connection and his memorial window in St Peter’s Church Oare.

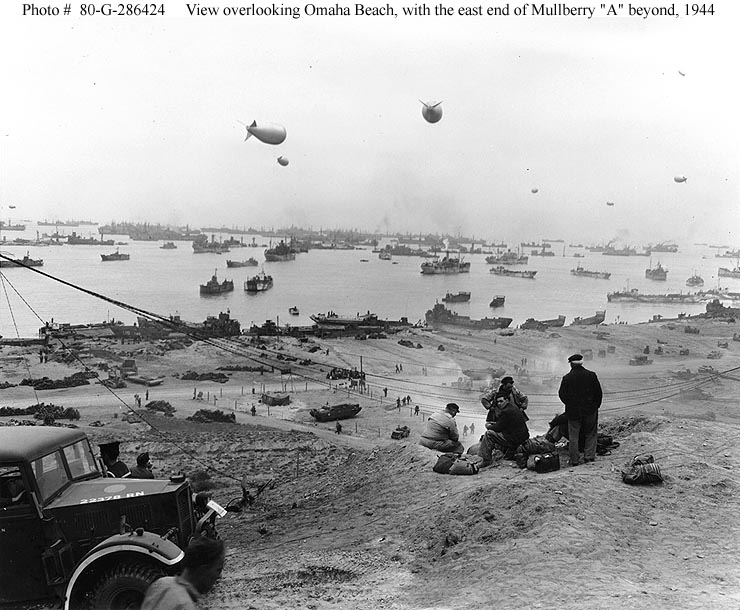

Next are the two harbours: Mulberry A, operated by the Americans at Omaha Beach and the British Mulberry B at Arromanches. The name was pure coincidence – it was the next one in the codebook. The idea of using artificial harbours on the Normandy coast was first aired by Winston Churchill in May 1942. In a memo to Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, headed ‘Piers for use on beaches’, he wrote: ‘They must float up and down with the tides. The anchor problem must be mastered. Let me have the best solution worked out. Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.’

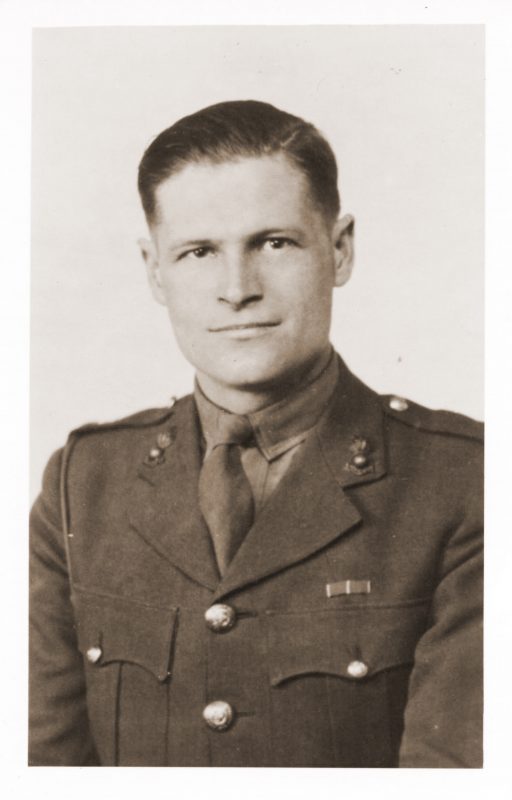

Allan Harry Beckett in 1945

By this time, Allan Beckett , who had volunteered for military service in 1939, was a young officer in the Royal Engineers, and had been seconded as an assistant to the Chief Bridging Instructor, Lt Col W T Everall. Beckett records in his memoir of this period that he liked working with Everall, ‘who had a remarkable ability to get things done’. One day, on his return from his weekly visit to the War Office, Everall handed him a sketch marked ‘Top Secret’. There was no further explanation other than a caption reading ‘Piers for flat beaches’. As a keen sailor, asked Everall, could he make sense of it? (Beckett was a lifelong sailor and kept his yacht at Iron Wharf in winter and would be out on the Swale in summer.)

The beach at Arromanches

The sketch, wrote Beckett, was of a ‘mile-long series of pontoons, each with four legs looking like four-poster beds’. Legs, he thought, were an unnecessary complication for a floating bridge. ‘If you think you know how to do better,’ said Everall, ‘you must make it clear before next Monday when I shall be revisiting the War Office.’ Beckett rose to the challenge and produced a model of his proposed floating roadway. The War Office was enthusiastic, prototype bridge spans were built and tested against rival designs. Only Beckett’s bridge survived a howling gale. Ten miles of the roadway, codenamed Whale, were commissioned, and more than 2,000 of the Kite anchors he designed to secure them.

Omaha beach with Mulberry A beyond

The two harbours became operational on D-Day + 12 (18 June). On 19 June there was a violent storm lasting three days and Mulberry A was destroyed. Mulberry B survived and continued in use until the port of Antwerp was captured. During these five months, two million men, 500,000 vehicles and four million tonnes of supplies were moved using the roadway and harbour. For his work at Arromanches Allan Beckett was awarded a military MBE. He also received two special awards for inventors, the first for the development of the Kite anchor and the second for the design of the floating bridge. For the design of the Kite anchor his award was £3,000. He used the money to build a house at Farnborough, Kent, where he lived until his death in 2005, aged 91.

St Peter’s Church Oare

Mulberry trees feature again at St Peter’s Church Oare, where Allan Beckett worshipped and where he is buried. The small Grade I listed church dates from the 13th century. It is built on a ridge high above Oare Creek; winding paths descend the hill, revealing the marshes and the busy boatyard beyond. St Peter’s sits in a well-tended churchyard, where a mulberry tree has been planted in Allan Beckett’s memory. Inside the church, a magnificent stained glass memorial window, designed and made by Petri Anderson in 2011, depicts a graceful mulberry tree studded with red fruit. A Whale floating roadway and a Kite anchor are also included.

The churchyard looks out over Oare Creek

The window is a dignified tribute to a modest man, who was pre-eminently, said his son Tim, ‘a brilliant engineer, probably one of the best of his generation.’

St Peter’s Church Oare

Church Road

ME13 0TR

Text: Sarah. Photography: Lisa, Abbey Physic Community Garden