Words Amicia de Moubray Photographs Justin Croft, Amicia de Moubray and Posy Gentles

A tantalising glimpse of the Dawes tower

For many Faversham Lifers, one of the surprising joys of lockdown was the discovery of new walks in the countryside around Faversham. The enforced leisure, coupled with a quest to enliven the tedium of being cooped up, made lots of people keen to explore new routes.

I set out early one morning with fellow Faversham Life writers, Posy Gentles and Justin Croft, on a mission to find the mysterious, romantic-sounding, ruined tower that Posy had enticingly described, located in a wood near Mount Ephraim, the ancestral home of the Dawes family. Driving north from Boughton Street on the Dawes Road, with Clay Pits Wood on our right, we parked at what the Dawes call the Cross Roads. Bridleways in two directions straddle the road. We opted for the northwards Tower Wood track which splits into two after about 150 yards. To the right is the Red Road through Blean Wood – so called as its core is made up of broken waste from an old pottery that once stood near the Cross Roads.

We forked left. At this point, there are truly spectacular far-reaching views encompassing Mount Ephraim and Nash Court, both handsome red-brick mansions, Hernhill church, and the Swale stretching out to the sea in the far distance. The panorama is every bit as fine as those much better known views over the Weald from the Greensand Way.

Our quest for the tower (marked on the Ordnance Survey map) at first proved somewhat difficult as we hacked through a seemingly endless jungle of overgrown rhododendrons and peered through the dense vegetation for any sign of a tower in the depths of Crockham Wood. A century ago it was very different, as Sandys Dawes told me. ‘During the time of my great-grandfather, Willie (he died in 1920), the Tower Road was made with benches for the public to sit on to enjoy the views. Family hearsay is that the rhododendrons were planted to remind my great-granny of Scotland. She was the daughter of James Simpson, from Banff, a noted distiller of quality whisky.’

The elusive tower emerges from the rhododendrons

At last we glimpsed the top of the tower and made our way to it, feeling triumphant. Local legend is that it was built by the Dawes family, who were in shipping at the time, to enable them to watch their boats heading to the London docks. But Sandys says: ‘I can’t even be sure whether it was built by my great-great-grandfather, Sir Edwyn Dawes who died in 1903, or his son, Willie. I take the simple line that both my ancestors were heavily involved in shipping and took pleasure in taking their guests to the top of the tower to look out over the Swale Estuary and the Thames to see their boats.’

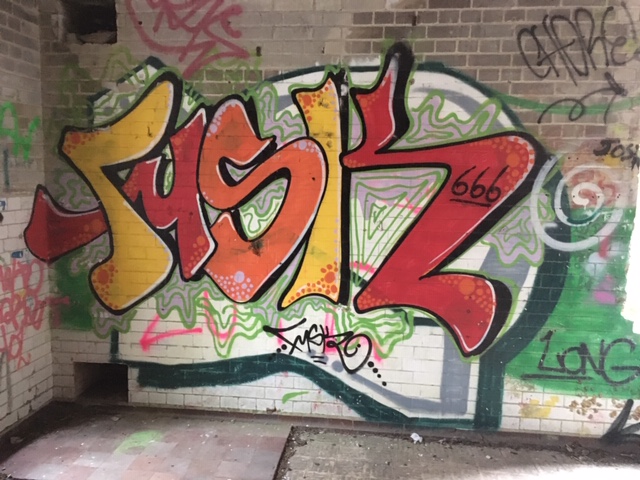

Graffiti inside the Dawes tower

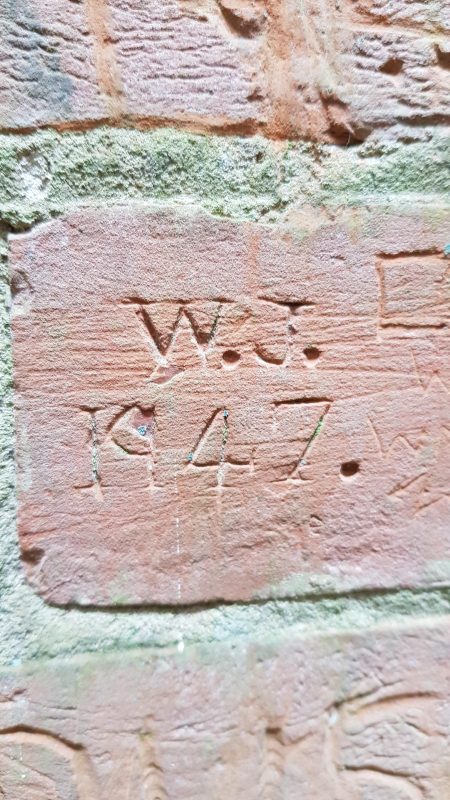

The knapped flints with stone dressings

Standing inside the tower looking heavenward

Originally the brick tower, faced with knapped flints and stone dressings, had two storeys. The second floor was crowned by a turret. Sadly, the iron spiral staircase vanished a long time ago, but it is easy to see where it was. The brick walls are covered in graffiti, some of it beautifully executed.

Sandys would have loved to restore the tower to its former glory, but it would be a big and expensive task. Alas it was already fairly decrepit in his childhood in the late 1950s and was, at one time, used to rear pheasants. Today, its forlorn state, as it lurks amongst dense undergrowth, imbues it with intrigue for anyone stumbling upon it by accident when out for a country stroll.

We retraced our steps to the Cross Roads, setting off in the opposite direction for Clay Pits Wood along a bosky path lined with chestnuts, hornbeam, beech and oak. We were in search of yet another abandoned structure, but this time one that is not marked on any map. On the left, we glimpsed a few concrete mounds which heralded a larger structure in the distance, poking out of a sea of brambles. We picked our through the scrub and stepped into an extraordinary survival – a radar station built by the Air Ministry in 1937. It was one in a series of similar stations called Chain Home stations constructed to give warning of an air attack by the Germans.

The derelict radar station at Dunkirk

This was among the first five operational stations which made up the so-called Estuary Chain Home layout established in 1936-8 to provide long range early warning for high-flying enemy aircraft in the Thames Estuary and the south-east approaches to London. The site was controlled by No 11 Group Fighter Command and the area covered some 30 acres. Initially there were four steel 360-feet-high transmitting towers spaced 180 feet apart and four 240-feet, timber receiver towers in a rhombic pattern around the receiver block. Only one steel tower survives. There were 150 people living in the camp located on the north side of the site. In 1938, RAF Dunkirk went into alert during the Munich crisis and was kept in readiness right up to the outbreak of the war.

Local oral tradition is that Winston Churchill used to stay nearby with relations and, knowing the area well, decided that it would be ideal for a radar station.

There is now a preservation order on the site as it is one of only seven Chain Home sites nationally which are virtually complete with ground structures and layout still visible and interior untouched. But this clearly doesn’t deter the local youth using it from time to time for beer sessions against a backdrop of some rather lurid murals emblazoning the walls.

Further on, a simple steel nameplate on a gate, with achingly cool lettering, states ‘Bofors Tower’. Originally this was a large concrete tower with an aircraft gun to protect the radar station. It was converted by the architect owners into a house a few years ago.

Bofors Tower

The track ends at a picturesque Victorian cottage with an astonishingly contemporary glass extension to its rear. At this point, one has to turn around and retrace the route back, to finish a fascinating historical walk with outstanding views to be savoured.

Text: Amicia. Photographs: Amicia, Posy and Justin