Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft and British Museum (used under Creative Commons licensing)

Our recent article on manhole covers touched a chord. Several people shared our dismay at the silent loss of the iconic Air Ministry cover; others offered non gender-specific names (‘street operculi’ is the best). We received some additional sightings of interesting examples, some amazing technical details about how certain cellar coverings directed light prismatically into the cellars below. There is evidently a lot of love for these lowly aspects of our streetscape and it’s heartening to see how much people care about the ground they walk on.

The Faversham Pavement Act, 1789

Quite by coincidence an original copy of the Faversham Pavement Act of 1789 arrived on my desk last month (yes, I tend to collect such things). Also known as the Faversham Improvement Act, I can’t resist sharing it here. Passed on the 24 June 1789, its full-title is:

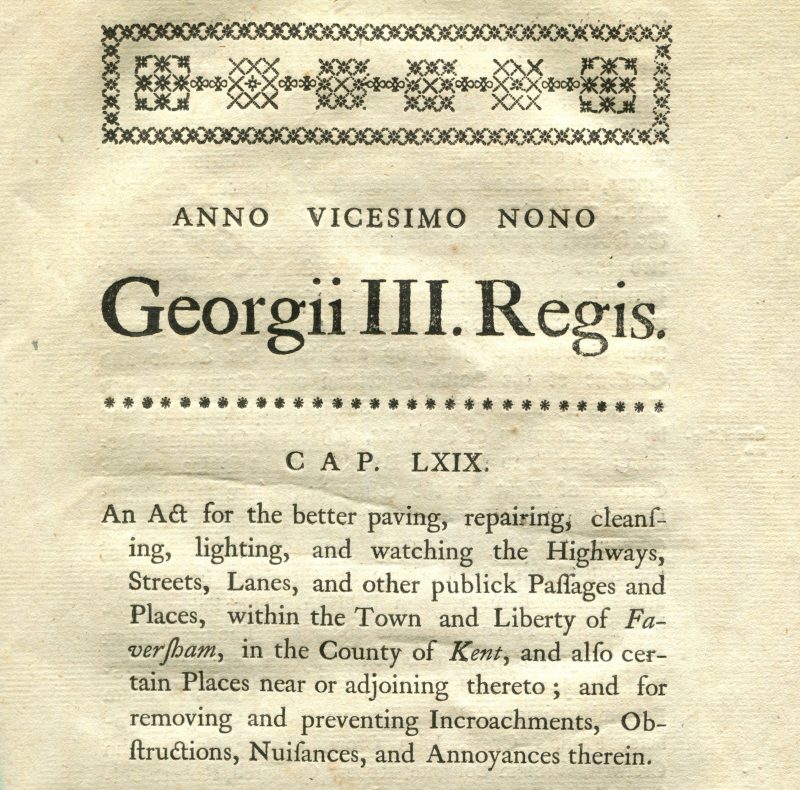

An Act for the better paving, repairing, cleansing, lighting and watching the Highways, Streets, Lanes, and other Public Passages and Places within the Town and Liberty of Faversham in the County of Kent; and also certain Places near or adjoining thereto; and for removing and preventing Encroachments, Obstructions, Nuisances, and Annoyances therein.

The Faversham Pavement Act, 1789. Something of a typographic wonder.

Running to many pages of dense and deliberately authoritative black letter gothic text, the act, in short, set up a local commission for the paving of the town centre. The Faversham Pavement Commission unsurprisingly included a host of local worthies: John and Julius Shepherd (brewers), Francis Crow (clockmaker), Stephen Doorne (bookseller), Henry Gibbs (surgeon), John Rigden (brewer) and Edward Jacob (surgeon, naturalist and antiquary). They were to raise money by setting a rate on anyone owning or occupying land or property in the town and set about repairing or installing new pavements as they saw fit.

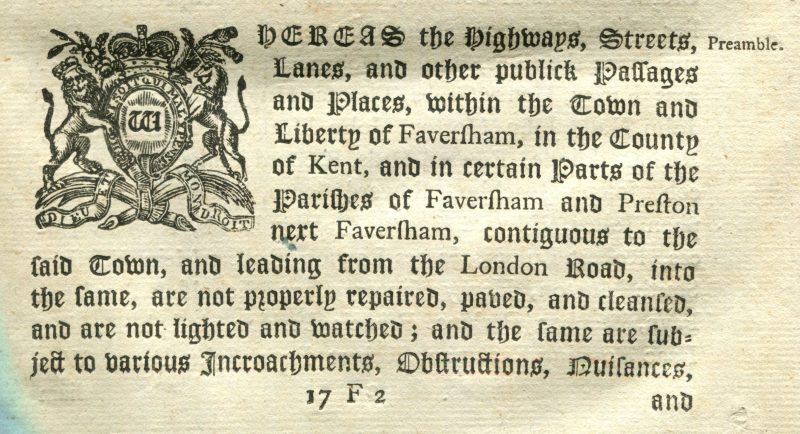

Preamble, in black letter type

To be sure, this wasn’t the first time Faversham was paved. The unfortunate Thomas Arden and his town council enacted paving for West Street, Preston Street and Key Lane in 1548, also raising a new rate to pay for it. Abbey Street and Court Street were not paved until 1636, the latter reputedly reusing materials purloined from the abbey ruins. There are knowledgeable people who can point out the abbey stones in the streets, but it’s hard to know how much genuine historic paving survives in the town.

Middle Row mosaic, or a pavement puzzle. Stones of different ages and origins.

As we know, roads and pavements are taken up and relaid over and over again. Much original material has been kept in the Court Street and Middle Row area but understanding which bits are really eighteenth century or even earlier is a puzzle. Any given square yard of stone paving seems to have a mosaic of different pieces of different ages. The more you look the more bewildering it becomes.

Paving stone parade. Drain repairs in Middle Row, with several different stones laid out (and hopefully to be relaid)

But the 1789 Pavement Act actually went much further than just footpaths — the commissioners also put up street signs. They ‘shall and may describe and determine the Limits and Extent of the several Streets, Lanes, Passages and Places …. And shall and may cause to be placed, on a conspicuous Part of some House or other Building at or near the End Corner of every such Street, Lane, Passage or Place, the Name by which such Street, Lane, Passage or Place, is usually or properly, or shall hereafter be called or named.’ Not only that, but the Act instructed that every house, shop and warehouse in every street should be given a number ‘placed or painted on the door’. There were penalties for vandalism and defacement.

I confess I’d never thought about the origin of street signs in Faversham, nor about house numbers, but it seems they were first put up in a systematic way after the Pavement Act of 1789.

There were improvements too to the cleanliness of the town. Inhabitants were required to keep the new pavements clean outside their houses, each one instructed to ‘sweep and cleanse, or cause to be swept and cleansed, the said Foot Pavement, and also the Gutter and Channel of the Carriage Way … between the Hours of Six and Ten of the Clock in the forenoon (Sundays excepted) upon Pain of forfeiting Five Shillings for every Neglect therein’. Ouch.

Street cleaners called scavengers were appointed, bringing carts into the town and ringing a bell to warn the townspeople for their arrival, taking away refuse and dumping it at an appointed spot. No-one else was permitted to do this, though inhabitants were allowed to collect and hold onto animal dung for their own gardens. ‘Necessary houses’ and privies could only be emptied between the hours of eleven at night to four in the morning. Several public nuisances in the streets were identified: wheelbarrows, carts and sledges left on pavements, slaughtering animals in the streets, cleaning out barrels, chopping wood and leaving cellar hatches open at night.

Acts and laws are always fascinating for what they forbid — it’s the list of ‘Encroachments, Obstructions, Nuisances, and Annoyances’ that I find most interesting in the Faversham act, implying of course that people were actually doing these things in the streets in 1789. Offenders against the act might include shopkeepers who ‘hang up or expose to Sale any Goods, Wares, or Merchandizes, or any other Matter of Thing, upon any Flap, Window, or otherwise, so as to obstruct of incommode the Passage of any of the said Footpaths or Carriageways’ or people who lit bonfires, slaughtered animals or threw fireworks (any ‘Squib, Serpent, Cracker or Firework’). Offences like this were subject to fines of between five and forty shillings.

Cock Throwing from William Hogarth’s ‘Four Stages of Cruelty’ prints 1751 (detail)

One gruesome detail turned my stomach, namely ‘cock throwing’, specifically outlawed in the act. I’d never heard of this and had to look it up. The Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore explains: A number of traditional sports, called ‘cock-threshing’, ‘throwing at cocks’, ‘cock-running’, were particularly popular at Shrovetide. In its basic form a live cock, or hen, is tied by one leg to a stake or other immovable object. Players take it in turn to throw heavy sticks at the bird, and the one who kills it wins it.

When I started glancing at manhole covers and paving stones, I’d no idea where it would lead me, but I’ll stick to the path and continue to enjoy the surprising journey into Faversham’s past.

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: Justin Croft and British Museum (used under Creative Commons licensing)