Words Justin Croft Photographs various

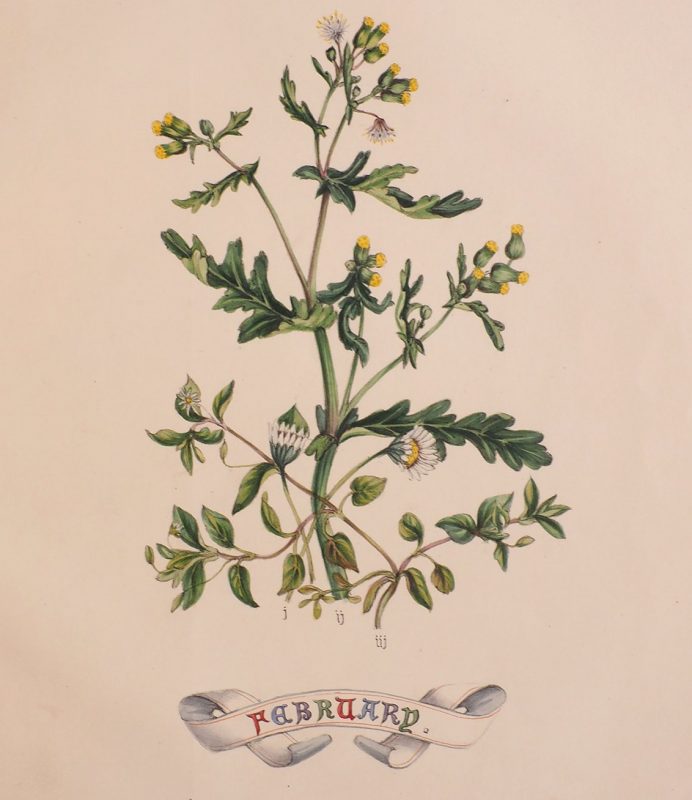

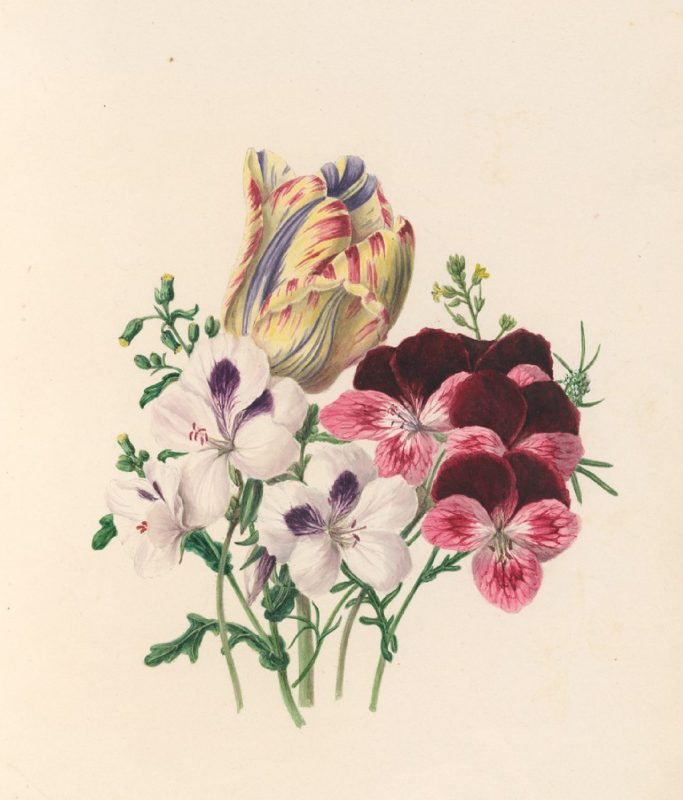

‘February’ from Jane Elizabeth Giraud’s The Floral Months

February is here and we are eagerly searching for signs of spring. I won’t be alone in scanning the undergrowth for green shoots pushing their way through last year’s decayed leaves. Already we have snowdrops, aconites, a few early daffodils and a hellebore or two — while supermarkets and social media are tempting us with the brighter colours of tulips and lilies, desperate to bring us spring before its time. But let’s be patient — there is much to appreciate in the muted colours of February.

With that in mind, I’ve been enjoying a lovely image of February flowers by Jane Elizabeth Giraud, Faversham’s own Victorian flower artist. It comes from her book The Floral Months published over 170 years ago in 1850. In this illustrated floral calendar, which has a flower picture for every month, Jane Giraud shows us just three humble flowering plants for February — weeds really — common daisy, groundsel and chickweed. She saves the bolder colours of spring for their rightful place in the later months.

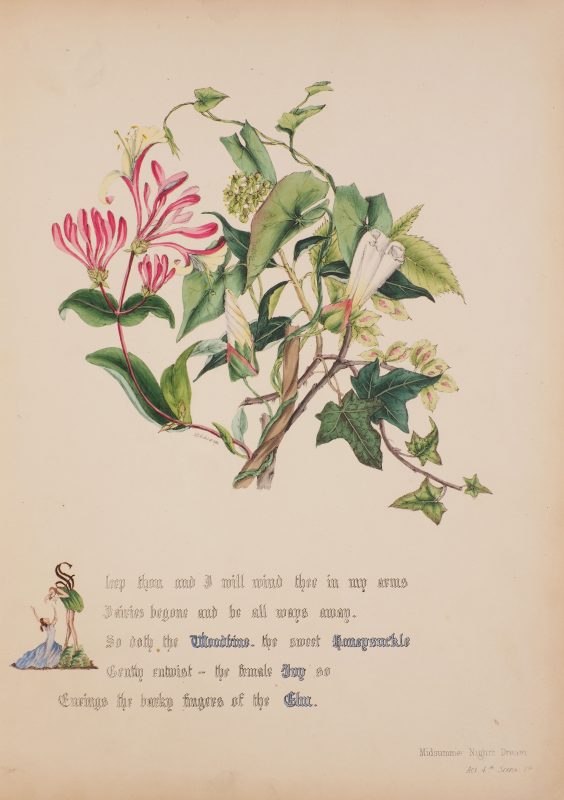

Midsummer Night’s Dream from The Flowers of Shakspeare

I’ve been researching Jane Giraud’s life and works for nearly a decade now and think she deserves to be better known in her native Faversham. She was born in 1810, daughter of John Thomas Giraud — descended from Huguenot immigrants — who became a surgeon and mayor of Faversham. Jane’s grandfather had been rector of St Catherine’s and a headmaster of the grammar school.

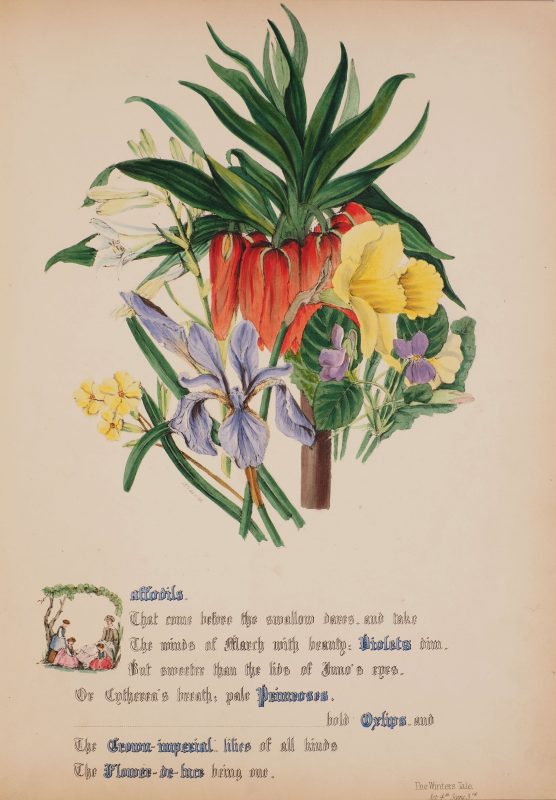

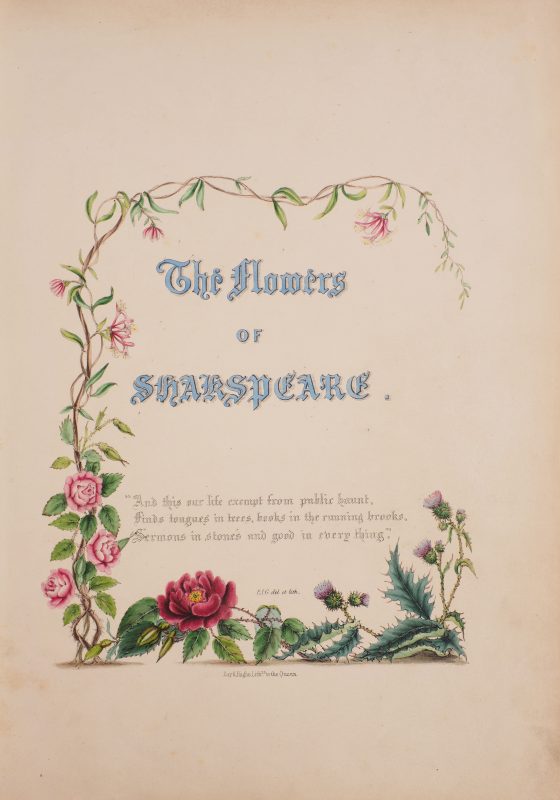

Like many young women of her age she took up flower painting as a pastime and she became remarkably successful, publishing no less than three illustrated books. The first, titled The Flowers of Shakspeare, illustrated the many botanical references in Shakespeare’s plays and appeared in 1845. It was followed in 1846 by The Flowers of Milton illustrating Paradise Lost and Paradise Regain’d and then finally by The Floral Months of 1850.

The Flowers of Milton

While her watercolours were typical of the period, Jane’s success in having them published is what marks her out. It probably goes without saying that publishing as a woman in this era was an exception rather than the norm — though botanical illustration was one area where it was possible. A generation earlier for example, Jane Loudon had produced a series of very well-received flower books, while the most successful female botanical artist of Jane Giraud’s time was the Rochester-born Anne Pratt, whose books all became bestsellers. Like Loudon, Jane Giraud benefitted from the printing technology of lithography and the illustrations in all her books are lithographs, which were then individually hand-finished in watercolour.

Lithography (literally ‘stone printing’) was a process which allowed an artist to draw with a wax crayon directly onto the smooth polished surface of a slab of limestone, rather than relying on an engraver to transfer their pictures onto copper plates or blocks of wood. The stone surface was chemically treated so that the drawn lines absorbed printer’s ink rolled onto the stone. Once the excess ink was wiped away from the remaining smooth surface, it left just the artist’s inked lines, which were transferred onto paper as the lithographic stone was passed through a rolling press. It is a rather magical process — of which you’ll find some excellent demonstrations on YouTube.

The Flowers of Shakspeare

All Jane Giraud’s books were printed in London by the firm of Day & Haghe, lithographers to Queen Victoria, and I’m still intrigued as to how a Faversham flower painter came to their notice. The firm had recently pioneered a clever modification of the lithographic process which dispensed with the huge, heavy and unwieldy lithographic stones by using instead sheets of specially prepared sheets of zinc, which were much more portable and convenient. It was cutting-edge technology, and it is this method that Jane Giraud used for her flower books. One wonders whether she worked here in Faversham, sending her plates up to London, or whether she travelled to London and worked at Day & Haghe’s studios.

However they came to publication, her books were much appreciated and sold well. The Flowers of Shakspeare was by far the most popular and seems to have been reprinted in three successive editions, producing hundreds, perhaps thousands of copies. Obviously Day & Hague knew their market and this was the era of the Victorian gift book, where publishers vied with each other to produce handsome volumes, well illustrated in eyecatching gilt-stamped cloth bindings, partly for the Christmas market. It seems that Jane too played a part in the marketing of her work — I once saw a copy of The Flowers of Shakspeare containing a sales receipt, personally signed by Jane Giraud, suggesting she sold them directly to customers as well as having them sold in bookshops.

Watercolour from The Fête of the Flowers

The printed books were obviously just the finished product of Jane’s art, and like most artists she must have produced hundreds of preliminary drawings, presumably filling albums and portfolios — none of which are known to survive. I’m aware of only one collection of her original watercolours, now preserved in the collections of the garden museum at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC. I was fortunate to be able to examine them myself several years ago, but anyone can now look at them, since they have been digitised in their entirety. I’d recommend having a close look at this exquisite album entitled The Fête of the Flowers at this link, taking advantage of the zoom functions to look closely at the watercolour technique. While Giraud’s lithographed books are delightful, it is only in these originals that we can see her rich appreciation of botanical detail and texture, and her skill in translating it in paint onto paper.

Watercolour from The Fête of the Flowers

Feasting on the colours of the variegated ‘broken’ tulip here, or the feathery foliage of the crimson pheasant’s eye, and the velvety texture of an early damask rose are more than enough to sustain me as we patiently count the days of February — the shortest month — and await the coming of spring.

Watercolour from The Fête of the Flowers

Thanks to Anatole Tchikine at Dumbarton Oaks for his assistance with the images of The Fête of the Flowers from the Harvard Digitistation, used here under the Creative Commons Licence, and to Rachel Thapa-Chhetri for the other pictures. I’m also grateful to the historian of lithography, Michael Twyman, for sharing information about Giraud’s lithographic processes.

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: various