Words Justin Croft Photographs Justin Croft

Red-lipped and still rosy-cheeked, an arresting face stares up at us. The body lies inert. Dressed in a scarlet gown and green skirts, a white headscarf barely conceals a tangle of thick red hair. Hands, unnaturally large, dangle from ungainly arms. A pair of shiny shoes grace tiny feet, barely attached to crumpled limbs.

Alice Arden as a marionette puppet (Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre, Faversham)

This must be one of Faversham’s strangest and most unsettling artefacts. Looking for all the world like the victim of a terrible crime, this is actually Alice Arden. Not murdered ― but a murderer, and the antihero of one of the oldest ‘true crime’ stories in English literature. Recreated as a string puppet (or ‘marionette’) in the 1940s, this puppet-Alice was used for local performances of the 16th century tragedy of Arden of Feversham. With her strings newly untangled, she’s preserved in the Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre, on pillows of crisp acid-free tissue paper. Rarely displayed because of her fragility, Faversham Life was lucky to have Heather Wootton, volunteer curator, bring this curious homemade puppet out for us to see. Heather pointed out the papier-mâché construction of the head and all the clothing details ― which must surely be upcycled fabrics of the 1940s ― and the challenge of keeping the fragile strings in order.

Alice Arden’s papier-mâché head

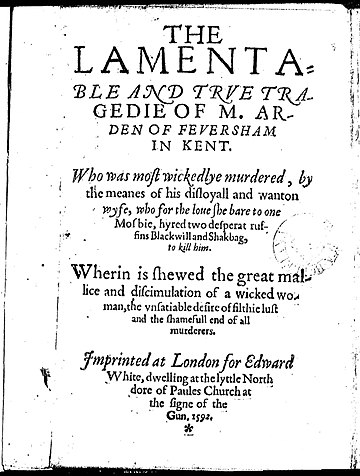

The Alice puppet is just one relic of the Arden story which has preoccupied locals for centuries. The play Arden of Feversham is largely based on the gruesome murder of an unpopular mayor, Thomas Arden, by his wife, Alice, her lover and accomplices in the year 1551. The case was recorded in local records and widely reported at the time, before being written up in full by Raphael Holinshed in his famous Chronicles, published in 1577. Soon after, the story was dramatized and turned into the play we know today, published in 1592 as The Lamentable and True Tragedie of M Arden of Feversham in Kent. No one knows for certain who wrote it, and it was probably a collaborative effort. What is increasingly certain however, is that parts of it are the work of William Shakespeare. Always suspected but never proven, recent analysis of the text suggest that certain scenes and passages do bear the hallmarks of the Bard himself.

The Lamentable and True Tragedie of M Arden of Feversham in Kent, 1592

Prominent historian Professor Catherine Richardson, who happens to be a local resident, has recently published a brilliant new edition of Arden (Arden Early Modern Drama, 2022) which is highly recommended for anyone interested in the play and its origins in real life Faversham history. In her wide ranging introduction, Richardson explores the tale and the text, but also the way in which local people have responded to the drama over the centuries. Fascinatingly, she uncovers the long tradition of local performances in Faversham ― not just traditional productions but performances with puppets too. The play itself was not, of course, home grown and was probably first performed in London, but there are records of London players performing in Faversham in the 16th century and Arden might well have been in their repertoire. By the 18th century, it was regularly performed in the town by local actors, beginning a tradition that has continued until recent times, as many of our readers will recall.

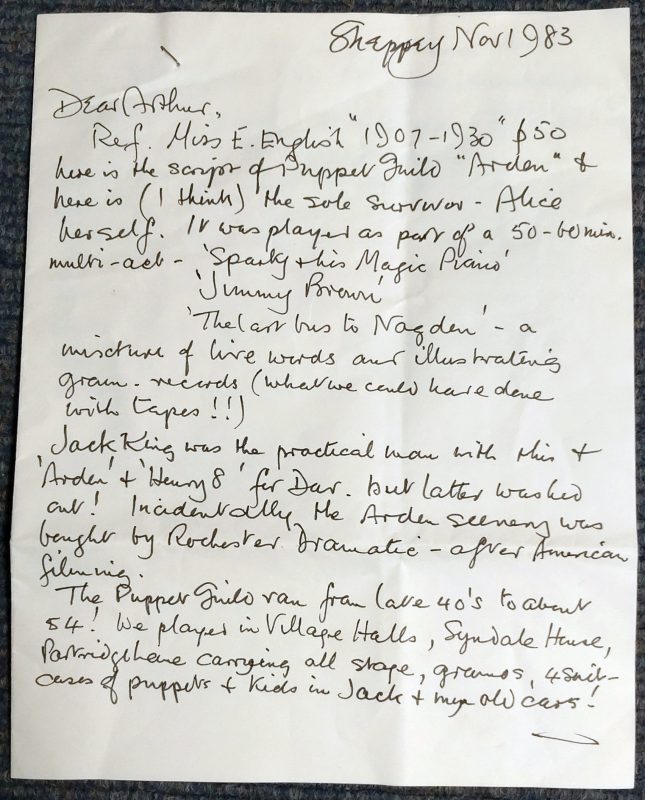

Donor’s letter (Fleur de Lis Heritage Centre, Faversham)

Arden could have been performed with puppets as far back as the 18th century, and marionette (string puppet) shows seem to have been increasingly popular in the 19th and 20th centuries as a cheap and portable alternative to professional theatre. As we see from her costume, ‘our’ Alice dates from the immediate post-war era ― a time of make-do-and-mend if ever there was one. She was donated to the Fleur museum in the 1980s by an original member of the Faversham Puppet Guild who performed in local halls from the 1940s to the mid-1950s. She seems to be the sole survivor of a colourful cast of a kind of variety show. Puppet Guild performances lasted around an hour, with Arden of Feversham sandwiched between tableaux of Sparky and his Magic Piano, Jimmy Brown and The Last Bus to Nagden, all performed to gramophone backing tracks. We’d love to know what The Last Bus entailed in particular, but it’s striking that Arden was whistled through in a matter of minutes. It must have been a knockabout affair, more Punch and Judy than Globe Theatre, with each successive attempt on Arden’s life and all the subtle psychology of the lovers’ plot compressed into a quick resumé. Alice ― Faversham’s own Lady Macbeth ― was transformed into the very image of the scarlet woman.

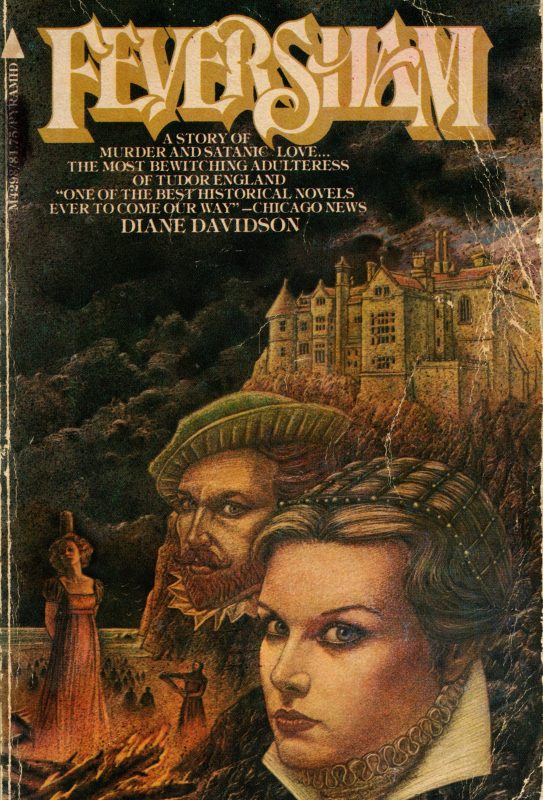

Feversham, Diane Davidson, 1969 (this paperback 1971)

We can’t get away from the violence and tragedy of Arden ― not only Arden dies, but all the protagonists, including Alice, are sentenced to death for their crimes. Perhaps performing it as a puppet show somehow gave distance to the grim facts of the case, but just as the domestic violence of traditional Punch and Judy leaves an unpleasant impression on modern audiences, Arden is not an easy play to take. Nonetheless, it has inspired many, far beyond the bounds of Faversham.

In France for example, the writer André Gide was a fan, making a French translation in the 1930s which has only recently been published (Arden de Feversham, Gallimard, 2019). In America it was transformed into a historical shocker by a California high school teacher, Diane Davidson (Feversham, 1969, now out of print). Billed as ‘A story of murder and satanic love … the most bewitching adulteress of Tudor England’ and a little optimistically as ‘One of the best historical novels ever to come our way’, it was a popular paperback in the early 1970s on both sides of the Atlantic. It is carefully researched in historical and geographical terms and is actually quite a good read. Theatrical productions will no doubt continue, especially now Shakespeare’s contribution to the original seems likely. While theatre is alive and well in Faversham, we have no news of local revivals. Alice Arden remains safely wrapped up in her archive box. For now.

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: Justin Croft