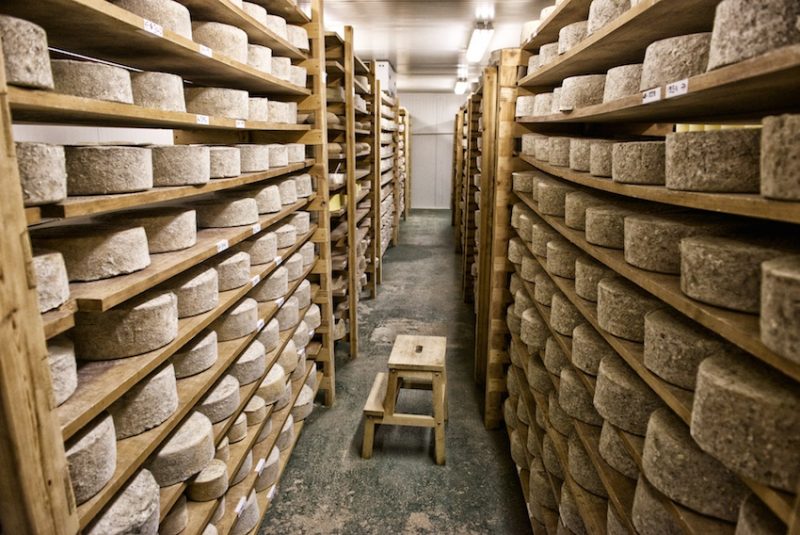

Harmonious lines of ripening cheeses

Last year, Britain overtook France to become the world’s top cheese producer, with 700 varieties (100 more than France). It’s not just on volume that we are showing the way: some of Britain’s best artisan cheesemakers are crossing the Channel and selling their award-winning cheeses to the French – our cheddar-type hard cheeses go particularly well with robust reds such as Chateauneuf-du-Pape.

Jane next to some of her awards

Jane Bowyer is the hands-on owner of the much-lauded Cheesemakers of Canterbury, which is not just winning awards nationally and abroad (Ashmore Farmhouse won in the 2011 World Cheese Awards the Super Gold Medal, making it one of the top 50 cheeses in the world), but is now exporting to France. She explains why the French market is attractive: ‘It’s the ease of getting across there – and the people are interested. Artisan cheese is a very niche market and the French appreciate it – we’re finding we’re making more relationships in France perhaps than in London.’

The glorious cheddar-style Ashmore Farmhouse

A recent approach came from a development agency, Calais Promotion, which believes that Northern France and Kent, regardless of borders, are one region and they should be working together. With nearly two years of Brexit uncertainty still to go, they say that they will just get on with it and see how it goes. Jane agrees. She thinks it would be a bad day if a trade tariff was put on cheese, ‘but if someone wants to buy my cheese in France, Poland or Japan, surely I’m going to supply.’

Milk churns from Dargate Dairy

When Jane started Cheesemakers of Canterbury in 2007, she could draw on her 20 years’ experience in the dairy business, acquired as a result of the introduction by the European Union of milk quotas in 1984. At that time, Lamberhurst Farm in Dargate, where Jane now makes cheese, was a dairy farm. Under EU rules, the farmer, Marc Lhermette, could process raw milk on the farm without it counting as quota. He sold it as green top (unpasteurised) milk in plastic bags. By the time Jane went to work there, in 1987, the milk was being sold in cartons. Many farmers, she says, took advantage of the exemption by setting up cheesemaking or ice cream businesses.

More dairy equipment from the past

In 1992 the cows were sold, ‘so we had a dairy, but no milk,’ says Jane. She took over the business, which became Dargate Dairy. She had a milk tanker made, which is still in service. Milk came from a farmer at Throwley and then from the ‘spot’ market – ‘we could buy on a Sunday when milk was cheaper.’ In the mid 2000s, Dairy Crest started buying up independent dairies, and a lot of milkmen came to work for her. ‘We got up to about eight milk rounds covering North Kent and there were 12 to 13 people working here.’ Then the business hit a bad spell in 2006. Dairy Crest had been making advances. ‘We finally caved in and by the end of May it was all signed and sold.’

Ashmore label

‘We had this building,’ says Jane, ‘but not enough money to retire.’ However, serendipity was about to strike. ‘The same day as I sold the business I was commiserating with a bottle of red wine and the Farmers Weekly. I saw a small ad for “a cheese business for sale in the South”.’ Jane sent a form saying she was interested to a PO box number, and ‘a little portfolio came through.’ Jane met the cheesemakers, David and Pat Doble, who were ready to retire, and struck a deal. They passed on their skills, equipment and the recipe for Ashmore cheese, which came originally from a smallholders’ textbook published by the North of Scotland College of Agriculture. She then had six months to refurbish the dairy. ‘It was a year to the day, in May 2007, when we started making cheese.’

Ancient Ashmore and goats’ milk Gruff

The unpasteurised milk came then, as it still does, from Tom Castle’s herd of British Friesians at nearby Debden Farm in Petham. At first they just made Ashmore, and then, in response to customer demand, added Ashmore variants such as Ashmore Chilli or Mustard, also Canterbury Cobble, and from goat’s milk supplied by Ellie’s Dairy at Wychling, the semi-hard Gruff and Kelly’s Canterbury Goat. Ramsey is made from ewe’s milk from Warwickshire. In 2010 premises were acquired in Hastingleigh, near Wye, and equipped with the help of a Leader grant from the EU. This is where soft cheeses are made from pasteurised milk: the camembert-style Dargate Dumpy, made with ewe’s milk, Chaucer’s and Bowyer’s. Also in 2010, Cheesemakers of Canterbury were invited to have a concession in The Goods Shed in Canterbury. ‘It was another busy year,’ remarks Jane philosophically.

Owen supervises the separation of the curd from the whey

Cheesemakers of Canterbury now produce 20,000 tonnes of cheese a year, all of it made by hand, following techniques that have been used for thousands of years, and with a team of only nine people, many of whom have been there since the beginning. The most recent recruit, in his fourth week when I called, is Owen. Lisa and I watched him hard at work on the next batch of Ashmore. Making the cheese is quite a complex business – ‘science and alchemy,’ says Jane.

The horizontal and vertical curd knives, with the moulds in the background

It involves heating the milk in large sterilised vats, adding starter culture and rennet to coagulate the milk. The curd is cut into cubes with curd knives to release the whey, stirred for a while and allowed to settle. When the whey has been drained from the curd, it is laid out in bricks, which are weighed to work out how much salt to add, then put through the peg mill (the only mechanical part of the process). Acidity is checked throughout the day. The curd is scooped into moulds lined with cotton muslin, heaped high like a big steamed pudding. The ends of the muslin are folded over, a lid placed on top and the moulds then go into the light, stainless steel presses overnight or for at least 12 hours.

The curd is drained and then placed in moulds

The stainless steel light presses

The next stage requires removing the cheeses from the moulds and their muslin, washing everything and putting it all back together. They then go into the old cast iron presses, dating from 1850 to1900, where they are pressed hard for 24 hours.

The old cast iron presses

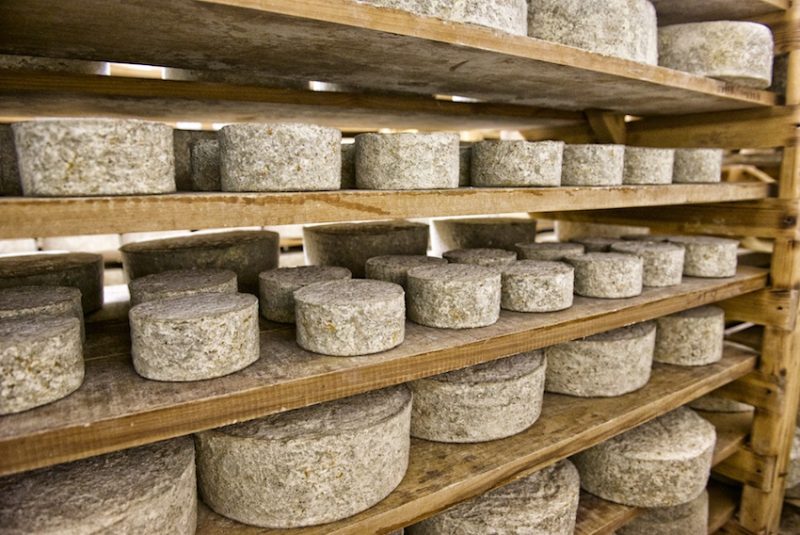

Next comes the maturing room where cheeses are lined up on old Parana pine racks, ‘nude’ so they can form their own rind. There is a strong smell of the stable, of ammonia. The cheeses have a number that denotes the day they were made. They are turned over daily to distribute the moisture. Each cheese is slapped on its side, then the top and sides stroked – a soft white dust (the mould in the funghi sense) floats off and can be detected in the air. Ashmore cheeses take at least five months to mature, Kelly’s Goat and Ramsey take three.

The fresher cheeses are on the top shelves, the more mature at the bottom

Alchemy at work in the maturing room

There is beauty in the harmonious lines of ripening cheeses, the newest on the top shelves of the racks, the oldest at the bottom. The youngest cheeses are stroked with ‘dirty’ hands – to spread the older moulds. It is here in the maturing room that the alchemy of cheesemaking is at its most potent. ‘Each day is different,’ says Jane, ‘every cheese is unique.’

Truckles ripening for the Christmas market

A whole wheel of Ashmore weighs 4-5 kilos and costs £80 – £100. As Christmas approaches, demand for Cheesemakers of Canterbury’s produce increases. Smaller cheeses, known as ‘truckles’ make excellent presents. They go through exactly the same process and have the same charm and character as the whole wheel. Cheesemakers of Canterbury have a stall at the Best of Faversham markets on the first and third Saturdays of each month. Their cheeses are also available at The Goods Shed, Canterbury (www.thegoodsshed.co.uk) and Macknade Fine Foods in the Selling Road, Faversham (www.macknade.com). Cheesemakers of Canterbury will be at the Faversham Christmas markets on 10 and 17 December, and, confirmation pending, at the Christmas Lights market on 26 November.

Cheesemakers of Canterbury

Lamberhurst Farm

Dargate

Faversham

Kent

ME13 9ES

Tel 01227 751741

www.cheesemakersofcanterbury.co.uk

Text: Sarah. Photography: Lisa