Words Justin Croft Photographs Various (including the Faversham Society)

In this electronic age it’s easy to think we know all about the past and that a click of the mouse will magically trawl the world’s catalogues of knowledge to answer any question we might have. How boring. And how utterly mistaken. There are still real discoveries to be made with careful observation of the things around us and the discernment of the human mind.

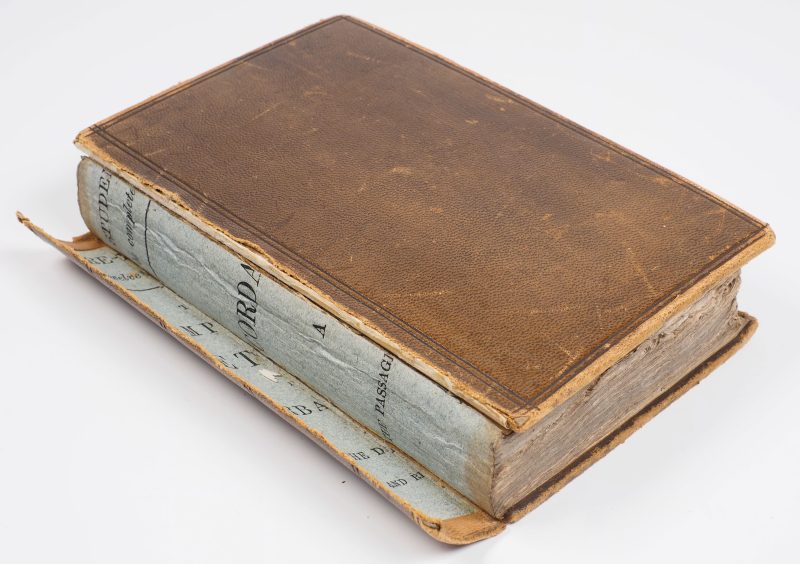

The book as it was found

A fine example is the book found by local resident Paul Moorbath in the attics of the Fleur de Lys museum. Paul has an eye for order and detail, an ideal qualification for his role as honorary librarian at the Fleur. He has a background in science, but before retirement he was a librarian at St Bart’s Hospital in London. He’s also a keen historian and remarks of his time at Bart’s, ‘In those days an old book was ten years old or even less’. The book he noticed in a quiet corner of the Fleur in Faversham was very much older than that. Carefully opening its covers, he saw its pages were printed in Gothic of ‘Black Letter’ type, a style mostly replaced by modern Roman fonts by the end of the sixteenth century. His instincts told him it was an early book and worth a second look.

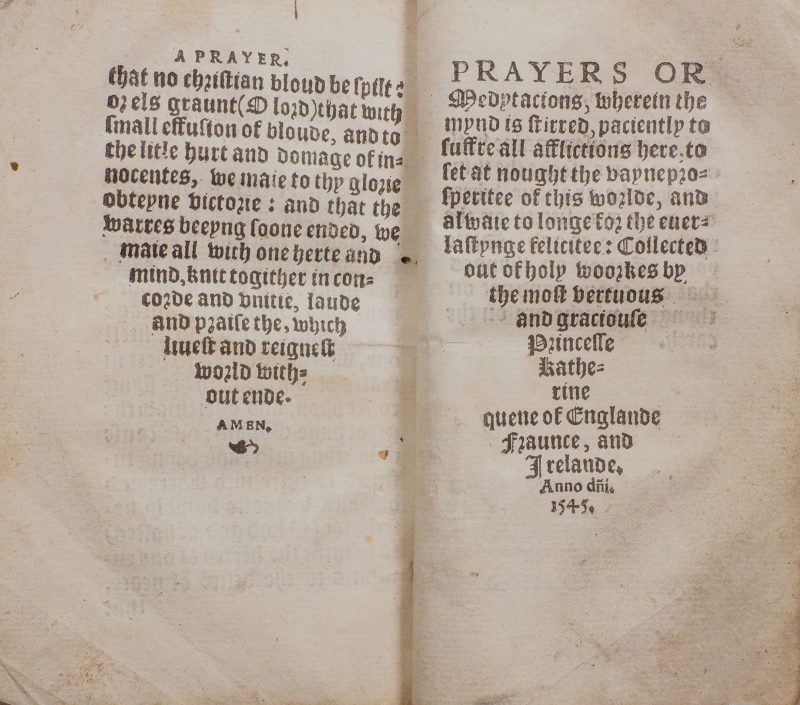

Prayers of Medytacions

Careful examination and consultation with other experts revealed the book was actually a compendium of fragments of three tiny books, all printed in the early sixteenth-century and bound together at an early date. One of them carried the date 1545 and was titled Prayers or Medytacions. Its title page attributed it to ‘the most vertuous and graciouse Princess Katherine’. And that’s where things got interesting.

Catherine Parr

Princess Katherine was none other than Catherine Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII ― remember the words of the matrimonial mnemonic: divorced, beheaded, died … divorced, beheaded, survived? She was indeed the author of the Prayers or Medytacions and historically this is an important book. When it was first printed in 1545 it was the first book by an English woman published under her own name. That’s incredibly significant set against the countless books by English men published with their names all over the title pages since the invention of printing in Europe just over 100 years before. This is also a rare book, with only a handful of the hundreds or even thousands of copies printed now surviving. Work is still ongoing to see exactly when Faversham’s example was printed (it’s a very early reprint, made in the time of Edward VI with the original 1545 date left on the title page). It’s a bibliographic puzzle which has already attracted the attention of scholars working at the British Library and across the Atlantic in North America.

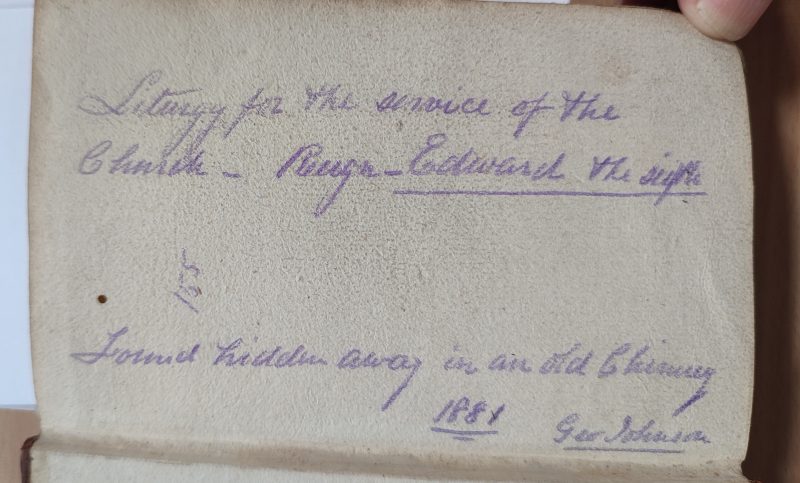

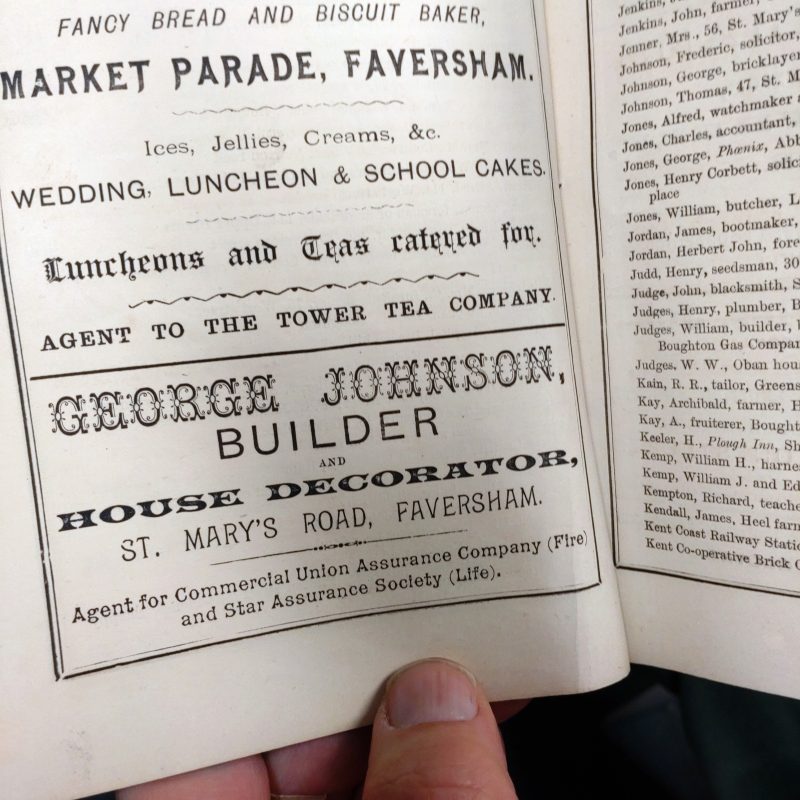

Paul points out another feature of the book he finds intriguing. On one of its endpapers there is a handwritten note (in purple indelible pencil) stating it was found in an old chimney in 1881 by a gentleman by the name of George Johnson. Mr Johnson was a well-known local builder, living in St Mary’s Road, working all over Faversham, so there’s a strong chance the book was disgorged from a very local chimney.

George Johnson, advert in the Faversham Institute Journal (Faversham Society copy).

Who put the book in the chimney in the first place? That’s a question that Paul Moorbath has been asking himself. He points out that all three fragments in the book belong to English prayer books. They were printed around the years 1545 to 1550 at a time when Protestantism and the Reformation were still in their ascendancy. English prayerbooks (rather than Latin) were acceptable and in some cases encouraged. Catherine Parr was one of the key figures in disseminating these texts in English so that ordinary people could pray in their mother tongue without the intercession of a priest. If you like a historical read, Parr’s remarkable literary and scholarly achievements (as well as her bravery) are beautifully and sensitively explored in Philippa Gregory’s book, The Taming of the Queen, which is easily available. But just a few years after Catherine, when the Catholic Mary Tudor came to the throne the Reformation went into reverse, with Mary’s vigorous suppression of English prayerbooks. Just a few miles from Faversham Protestant martyrs were burnt at the stake in Canterbury for their faith. So, it’s quite possible that whoever owned the Faversham prayerbook simply hid it. There are other examples of books being hidden this way in the fabric of buildings, especially chimneys, whose recesses made for safe but accessible hiding places. We can never be sure, given the evidence we have, but it’s a strong and chilling possibility.

The book is currently on display in the Fleur de Lys museum, where the Faversham Society report a pleasing stream of visitors over the summer. There’s much more to discover about the book and plans are afoot to let it travel temporarily to the British Library for formal identification and recording, so do go and have a look as soon as you can.

Read the BBC’s report of this discovery here.

The Fleur de Lys keeps is door open only with the help of volunteers like Paul. They are always looking for inquisitive, creative and organised people to join the team. If you have some time to spare and are interested have a look at their volunteering webpage or email volunteer@favershamsociety.org