Words Justin Croft Photographs The British Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Creative Commons)

King’s Field once occupied a large portion of the south-west quarter of Faversham. It’s an area now bordered by the London Road (once Roman Watling Street), The Mall, Stone Street, Ospringe Road and Stone Street — mainly filled with neat Edwardian streets, but also Ethelbert Road School and the railway line, which cuts right through its heart. But long before this, it was already a field with an extraordinary history ― as a Saxon burial ground.

Pendant from King’s Field, Faversham (early 600s AD), with gold filigree and polished garnets (The British Museum)

This incredible jewel was found somewhere on King’s Field in the middle of the 19th century, probably by workers excavating for the new London, Chatham and Dover railway line. It came from a grave, buried with its pagan owner as a symbol of power, wealth or status. It was immediately acquired by the local antiquary William Gibbs, who later donated it to the South Kensington Museums, from where it was transferred to The British Museum. It is an astonishing piece of art and craftsmanship, with its three beaked bird’s heads worked in polished garnet in a gold cloisonné setting on a background of worked filigree gold threads. It’s breathtaking on its own, but even more so when we learn that it was just one of many hundreds of pendants, brooches, bracelets, buckles, beads, pins and amulets dug up from other burials on the same plot of land. Almost all of them are now in The British Museum, whose online catalogue includes many high definition photographs of Faversham finds. Go to The British Museum Catalogue, and you’re in for a treat. There are other local treasures to look at, but it is the King’s Field treasure that is most startling. The museum’s digital photographs let us enlarge the images and zoom in on the exquisite detail of these pieces in a way hardly possibly peering through the glass of a museum case. At a time when museum visiting is so limited, these online displays can be hugely rewarding.

Disc brooch (centre) and two pendants from King’s Field Faversham (early 600s AD), with gold filigree and polished garnets (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

While most of these glorious pieces have ended up in The British Museum, some got away at an early date and are now in other museums ― some in Canterbury and Maidstone, more in The Victoria and Albert Museum, Liverpool Museum and The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The three beauties above are in The Metropolitan Museum in New York, and it’s worth looking at them in their online catalogue, which has an especially good zoom function for viewing the finer details.

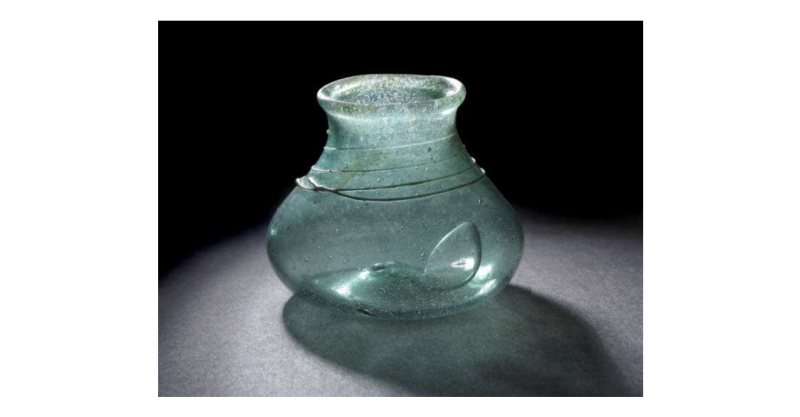

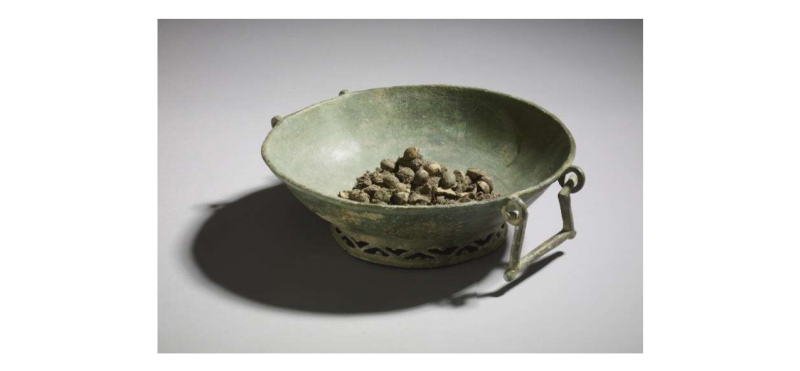

Why were these priceless pieces here, in Faversham? The answer lies in the burial customs of the Anglo-Saxon era (c 400-800 AD). Around the middle of that period (600-700 AD), our King’s Field was obviously a major burial ground for a prosperous pagan population, perhaps a royal settlement at the heart of the ancient kingdom of Kent. Before Christianity taught that we enter the world with nothing and leave with nothing, pagans believed that worldly possessions played a part in the afterlife and so they were often buried with possessions which best represented their status. In Faversham that status, for some, seemed to be very high indeed and men were buried with swords, knives and bodily adornments. Women’s graves especially, included exquisite examples of jewellery, often with gold and precious stones. Glass vessels were also popular grave goods, and some beautiful examples of Saxon-era glass are preserved in The Maison Dieu at Ospringe, The British Museum and The Corning Museum of Glass in New York. Again, you can look at some of them in their online catalogues.

Glass beaker from King’s Field, 7th century AD (The British Museum)

At the time the burial ground was in use, the settlement that became Faversham was a very special place indeed. Though we call the era after the Romans ‘Anglo-Saxon’, much of Kent was settled by a distinctive population from the Germanic-Scandinavian area called the Jutes, and it soon became a Jutish kingdom in its own right. Faversham may well have been an important, perhaps royal centre for the Jutes, which is probably how King’s Field by tradition, got its name. It’s also clear that the settlement played an important part in the making and trade of metalwork of exceptional quality, perhaps under royal patronage. Many of the raw materials (gold, silver and coloured stones) would have been imported from Europe. Some may have come from even further afield — it has been plausibly suggested that the finest red garnets set into some of the King’s Field jewels came from India. Given the richness of these jewels, it seems very likely that Faversham itself was where many of these treasures were made, and that its craftspeople were renowned as expert metalworkers. The name ‘Faversham’ doesn’t appear in records until later, but probably combines the Latin word ‘faber’ meaning ‘smith’ with the Saxon ‘ham’ or ‘settlement’.

I asked Geoffrey Munn, a leading jewellery historian and a familiar face on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow, what he made of the Faversham jewels. He says: ‘Gold and gemstones are incorruptible and, improbable as it seems, the jewellery from which it is made often emerges from centuries of burial as bright and perfect as the day it was made. This sense of permanence, a powerful emblem of immortality, fascinated our remote ancestors and made their precious ornaments a favourite in a wide range of domestic grave goods.’ Having worked with some of the finest jewellery in the world as a former court jeweller, Geoffrey’s assessment is especially striking: ‘The King’s Field hoard is technically and aesthetically superb but it is a good deal more than even that. It is a silent witness to the intelligence, taste and sophistication of our ancestors from whom we, against the same remarkable odds, have survived to the present day.’

Copper alloy Byzantine bowl from King’s Field: found containing hazelnuts (food for the afterlife or an offering to the gods?), 6th-7th century, made in the Eastern Mediterranean (The British Museum)

It’s sad to say that, apart from the excellent glass in The Maison Dieu at Ospringe, none of these treasures remains in Faversham. But seeing them in all their glorious detail in the catalogues of their various custodians is an experience we can all share. It’s also true that almost nothing of the original landscape of King’s Field survives, having been moulded by the excavations for the railway and brickfields, so it takes a real leap of the imagination to conjure up an image of the original burial ground. But once you know what was there, walking around the streets laid on top of it can be a rewarding experience. I’d recommend standing on the railway footbridge linking the two ends of St Anne’s Road on a soft autumn morning and looking east towards the sun rising over the railway tracks. Here you can just make out the curve of the land. In your mind’s eye, try to strip away the gleaming railway tracks and some of the garden sheds. An open field once lay here, perhaps dotted with grassy burial mounds, beneath which lay the glittering King’s Field treasures.

Pendant: gold, garnet and blue glass, 7th century, King’s Field (The British Museum)

For further reading on Saxon Faversham, I’d recommend the excellent book, Faversham in the Making by Pat Reid, Duncan Harrington and Mike Frohnsdorff (2018).

Text: Justin Croft. Photographs: The British Museum and The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Creative Commons)