Words Posy Gentles Photographs Various

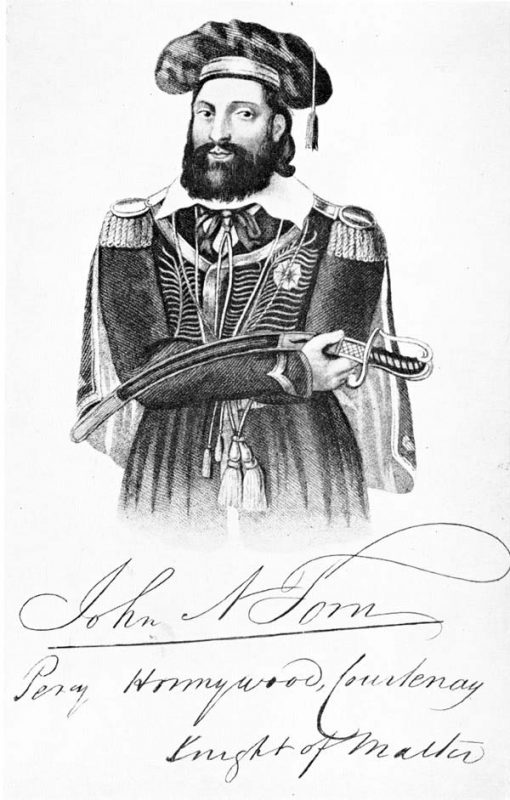

John Nichols Thom, the self-styled Sir William Percy Honeywood Courtenay, Knight of Malta, had a luxuriant coal-black beard and moustache and grew his hair long. He dressed flamboyantly in broad-brimmed hats and tasselled caps and wore ‘a very theatrical-looking tunic, upon the breast of which was embroidered in golden wire the Maltese Cross; while on his shoulders were thrown the ample folds of a cloak of Tyrian hue’. He called his sword Excalibur.

His life and extraordinary adventures ended violently in The Battle of Bossenden Wood in 1838, in Dunkirk between Hernhill and Boughton. He was 39 years old. Some believed him the Messiah, and others a madman.

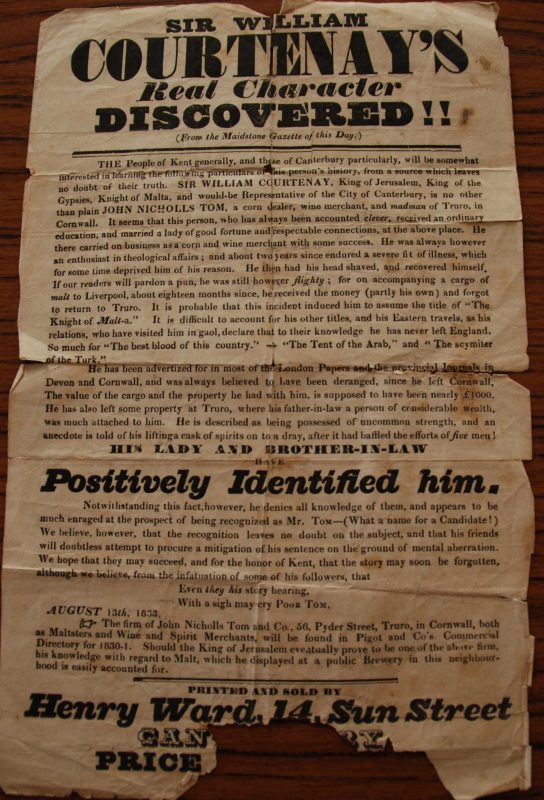

John Thom was a spirit merchant and maltster from Cornwall and an excellent cricketer. After a fire and an episode of madness, he set sail from Truro in 1831 with a cargo of malt. He wrote to his wife telling her that he had sold the malt and was going to France. She heard nothing more from him until a year later when she learnt that a man fitting his description and calling himself Sir William Courtenay was being held in Maidstone prison.

Thom had arrived in Canterbury in September 1832, an exotic and extravagant figure calling himself initially the Count Rothschild, before settling on Sir William Courtenay. He made such an impression with his costume and speeches insulting the mayor and archbishop that he was asked to stand as an independent candidate for Canterbury in the 1832 election. He polled 375 votes but lost. He turned his attention to publishing a weekly newspaper called The Lion which ran for eight issues and highlighted social injustices backed up abundantly by quotations from the scriptures.

Thom, or by this time Courtenay, ran into trouble in March the following year when he acted as a witness for the defence of a band of smugglers from Faversham. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to three months imprisonment and seven years transportation to Australia. His wife travelled to Kent, identified Courtenay as the missing maltster and told of his previous insanity. Refusing to admit to the connection, he was examined by two surgeons who declared him of unsound mind, and transferred him to the newly-opened Barming Heath Asylum (now St Andrew’s Park residential estate) in October 1833.

Courtenay was a well-behaved patient and upon petition, was given a free pardon and released in October 1837 on condition that he return to his family in Cornwall. This he did not but went instead to live with a local farmer, Mr Francis of Fairbrook Farm on the outskirts of Hernhill. He left after a disagreement to lodge with William Wills, then Mr Culver, both nearby.

While Courtenay had been in the asylum, the sufferings of the dispossessed and impoverished agricultural labourer in Kent had worsened. Their plight had erupted into the Swing Riots of 1830 when threshing machines were destroyed and there was rioting over low wages and the tithe system. In 1834, the Poor Law Amendment Act, The New Poor Law, intending to curb the costs of poor relief, ruled that relief would now only be given in workhouses, whose conditions should be so grim that all would shrink from applying.

Courtenay’s charismatic preachings and promises of a better life attracted a growing following in Hernhill, Boughton and Dunkirk. The lurid and salacious Newgate Calendar wrote after his death: ‘He was constant in his exertions among the poorer classes, and the influence which he obtained over them was extraordinary. The women excited their husbands and sons to join him, “because he was Christ, and unless they followed him, fire would come from Heaven and burn them”. They asserted, as he had declared, that “he had come to earth upon a cloud, and would go away from it on a cloud”; and instances were not infrequent in which the misguided people, the subjects of his imposture, had actually worshipped him as a God.’

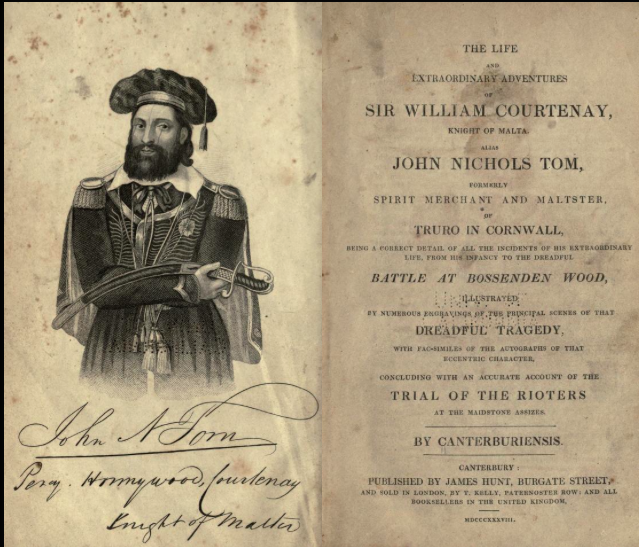

The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Sir William Courtenay was published within weeks of the dramatic events in Bossenden Wood under the pen-name, Canterburiensis. Again this is a sensational account which makes much of Courtenay’s madness. It describes how during the months leading up to what the magistrate’s warrant described as ‘the melancholy transactions that occurred on Thursday last, the 31st May, 1838’, Courtenay drummed up support from farmers and labourers, boasting that he was a gentleman of property which would come into his possession two years hence, and that he would give land to those who followed him according to their deserts. He borrowed money from farmers, promising that for every shilling he would return a pound. Canterburiensis writes: ‘These promises made many dupes, and enabled him to indulge in luxuries which excited the astonishment of those not acquainted with his resources, and made many believe that he was what he pretended to be – really a gentleman of property.’ Travelling around the local area and addressing their concerns about low wages and lack of work, Courtenay soon attracted a band of agricultural labourers, artisans and smallholders. Women, it was suggested by a contempory source, found him very attractive because of his big black beard.

On 29 May 1838, which was Oak Apple Day, a public holiday celebrating the Restoration, Courtenay and his followers began to march around the countryside with a flag and the symbol of protest, a loaf of bread on a pole. Their activities were peaceful but, possibly mindful of the Swing riots only eight years before, some landowners started to feel uneasy and on 31 May 1838, a local magistrate Dr Poore, issued a warrant for Courtenay’s arrest.

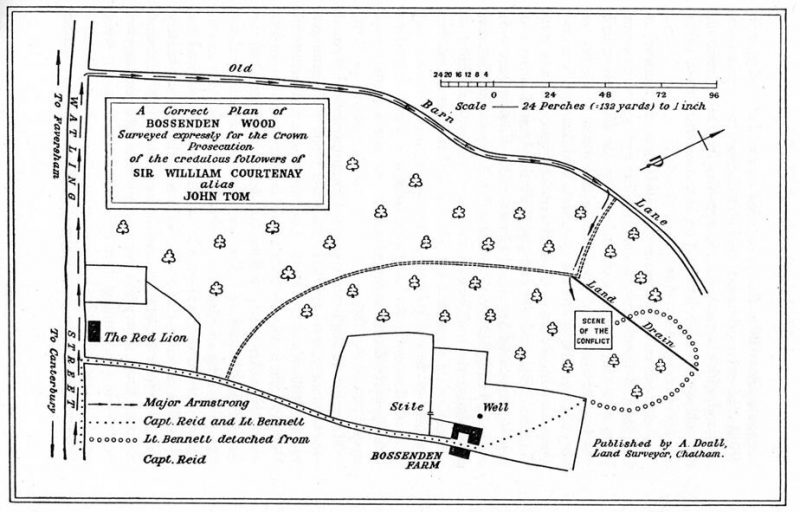

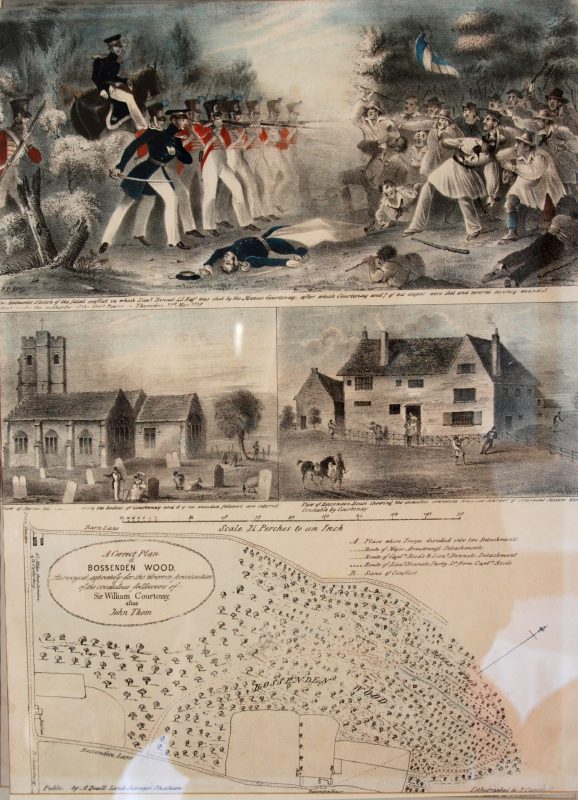

A plan of The Battle of Bossenden Wood. Hernhill.net

The parish constable of Boughton-under-Blean, his assistant, and his brother Nicholas Mears, set off early to Bossenden Farm where Tom and his followers were staying. Courtenay shot Nicholas Mears dead, and the constable and his assistant hastened to the magistrates who sent to Canterbury for assistance. A detachment of the 45th Foot was despatched from the barracks, led by Major Armstrong with three junior officers and about a hundred soldiers.

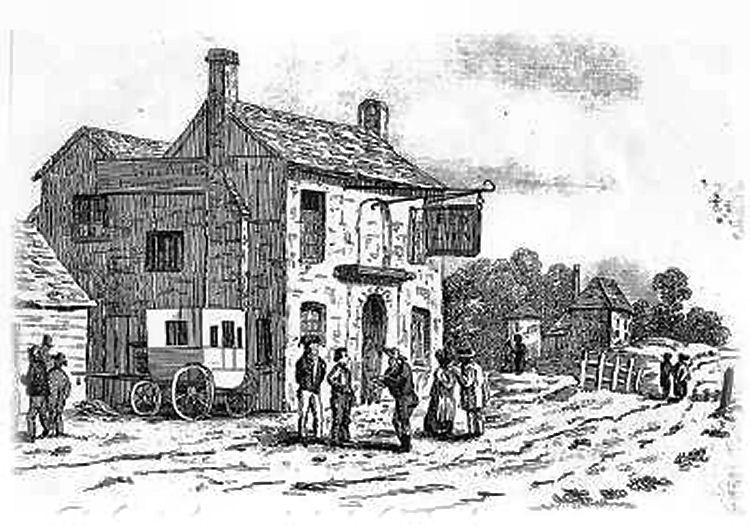

Mr Knatchbull, a local magistrate in Faversham, decided to deal with the matter himself and rode out with a posse of about 14 men on horseback to the osier beds near Fairbrook Farm where Courtenay and his men had decamped. They numbered 30 to 40 now as some of his followers had fled. There was a stand-off. Courtenay and his band retreated to Bossenden Wood. Dr Poore, Mr Knatchbull and more than a hundred soldiers of the 45th Foot were waiting at The Red Lion Inn in Dunkirk. William Courtenay was to be captured dead or alive.

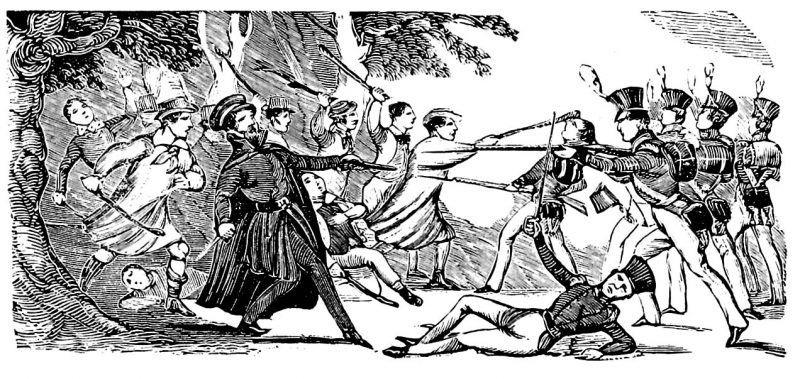

In a pincer movement, Major Armstrong led a troop into the wood through Old Barn Lane, while Captain Reid’s detachment entered the wood further to the east through Bossenden Farm. The battle lasted no more than a few minutes. On the rioters side, only Courtenay and William Wills had guns. The rest of the band were armed with cudgels and sticks. The only soldier to die was Lieutenant Bennett of Captain Reid’s party who advanced too impetuously to arrest Courtenay and was shot dead by Wills. George Catt, a special constable from Faversham, was fatally shot by a soldier who mistook him for a rioter. In seconds, eight of Courtenay’s party were dead and seven lay injured, one so seriously wounded that he died later that day.

The scene at Bossenden Wood apparently drawn by an eyewitness, for the Penny Satirist

Derek Bright in his essay, Shifting the Focus of Popular Accounts of the Dunkirk Uprising: The Convenient Preoccupation with Courtenay’s Mental Health, quotes Major Armstrong who led the 45th Infantry Regiment. He testified that he ‘never saw men more furious or mad-like in their attack upon us in my life’. ‘Major Armstrong,’ writes Bright, ‘is actually referring to an alleged attack by approximately thirty-five local men, the majority of whom are middle-aged and armed only with cudgels, against an armed detachment of the British army consisting of about one hundred and fifty infantrymen. Evidence at the inquest showed that some of the labourers had been both bayoneted and shot.’

So ended the ‘melancholy transaction’ at Bossenden Wood. The bodies were laid out in The Red Lion and, according to Canterburiensis, Courtenay ‘appeared to have been a most noble and muscular man. Notwithstanding his bloody and broken forehead, the fineness of his countenance was still perceptible, although those who had seen him whilst living, could scarcely recognize him, as, we know not by whose orders, his large whiskers and beard, as well as the hair of his head were shaven off, and from the meagre, diminutive forms, which were stretched at either side of him, he appeared as a giant amongst men of moderate size’.

The Red Lion, Dunkirk today . . .

. . . and in 1838

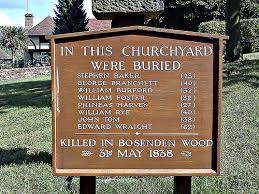

John Thom, Stephen Baker, George Branchett, William Burford, William Foster, Phineas Harvey, William Rye and Edward Wraight were buried in Hernhill churchyard. Lieutenant Bennett was buried in Canterbury Cathedral.

The dead from The Battle of Bossenden Wood are buried at Hernhill Church

An inquest was held at The White Horse in Boughton with the jury returning a verdict of justifiable homicide for the deaths of Courtenay and his followers. 30 men and two women were arrested over the next few days. These included, according to the Newgate Calendar, Thomas Mears alias Tyler (the cousin of the murdered Nicholas), Alexander Foad, William Nutting, William Price, James Goodwin, William Wills, William Spratt, John Spratt, John Silk, Edward Curling, Samuel Edwards, Sarah Culver, Thomas Myers alias Edward Wraight, Charles Hills, Thomas Ovenden, William Couchworth, Thomas Griggs, William Foad and Richard Foreman.

The Newgate Calendar account tells us: ‘The prisoners Mears, Alexander Foad and Couchworth were wounded. Foad was a respectable farmer, cultivating a farm of about sixty acres, and it was a matter of some surprise that he should have been implicated in so extraordinary a proceeding. The prisoner Sarah Culver was a woman about forty years of age, of respectable connexions, and possessing considerable property. She had been a devoted follower of Courtenay, but it was presumed that she, like him, was insane. The other prisoners were all persons of inferior station.’

By the standards of the day, sentencing was lenient – transportation and imprisonment with hard labour. It was considered, in their favour, that the defendants had fallen under the spell of the charismatic Sir William Courtenay.

The 45th Infantry Regiment went on to kill 20 Chartists the following year at Newport. Dunkirk, which had been described in 1800 by Edward Hasted in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, as ‘inhabited by low persons of suspicious characters, who sheltered themselves there, this being a place exempt from the jurisdiction of either hundred or parish’ got a church and a school in 1840.

Sources

Bossenden Wood Battle by David Shire Hernhill.net

Battle in Bossenden Wood – The strange story of Sir William Courtenay by PG Rogers, Oxford University Press, 1961

The Newgate Calendar, Thomas Mears and Others. The Canterbury Rioters 31st May 1838 by permission of www.exclassics.com

The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Sir William Courtenay by Cantabriensis 1838

Edward Hasted in The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, Volume 9, 1800